The Grail Tarot by John Matthews and Giovanni Caselli

This is a lavishly presented and, frankly, gorgeous thing to have in your possession, whether you are an adherent of Tarot – or not.

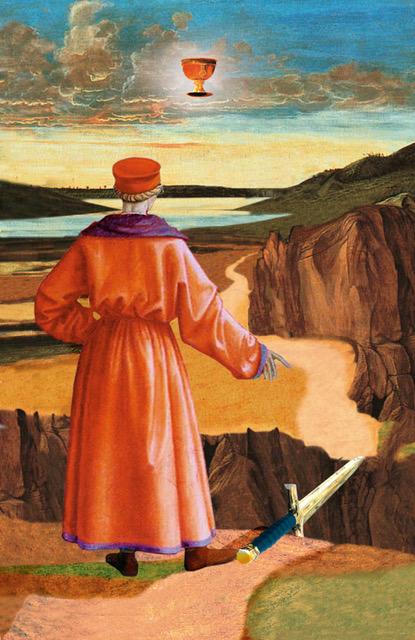

The quality of the art work is quite simply superb and what a splendid idea to present the cards so that, together, they form a tableau, one which would adorn the walls of any house very well indeed. The temptation is indeed very high to see them all gathered together in a suitably Italianate frame and hanging in pride of place in a room dedicated to the finer things in life.

The images presented are a coda of all the finest renaissance traditions and immediately transported me to the early Italian Art Room in the National Gallery.

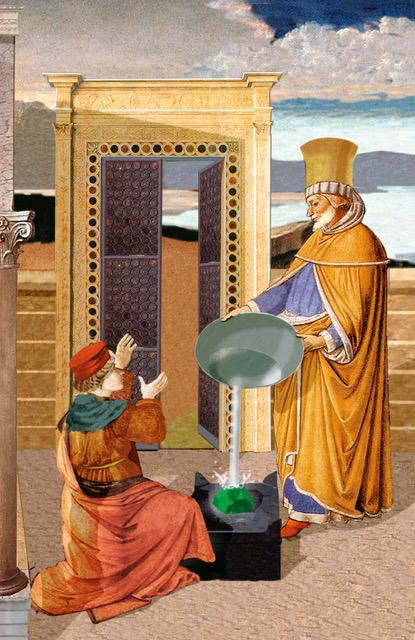

The images are clean, by this I do not mean not sterile or predictable even, but clean in the way that Italian art was presented as a fresh impetus in the early to late fifteenth century. These cards bear all of the hallmarks of the era, but with telling modern flourishes that contain clues for the quest of the Grail throughout. The human figures have a statuesque quality about them that radiates the central mystery of the Holy Grail: and added touches here and there inform us of the possible links to the Templars in a way that is majestic and yet enigmatic.

Card number 3 is a particularly fine example of the mystery as has been presented in books and academic papers. Here the Queen of Sheba is to be seen amidst four pillars of a portico, and with all of the splendour of her darkened skin as presented in the beautiful and mysterious Solomonic Song of Songs. Behind her is a pillared palace with a golden dome. The cupola of the dome is to be seen here as her royal crown as she holds up her left hand in the sign of heavenly blessing. She radiates from within golden and scarlet robes, so beloved of renaissance painters. To her right, behind her, we see, almost as an afterthought, a ship, upon its sail is a faint Red Cross. It is the Ship of Solomon – but here presented as a Templar ship: this could well be a sigil for the removal of the Templar treasure at the time of their arrest? Or perhaps a reference to their activities in Constantinople in the immediate prelude to the terrible events of 1204?

From this we can see that the author and the artist are very well read indeed on this most intriguing of mysteries.

The Grail is to be seen in some of the cards associated with the mysterious Green Stone described by Wolfram von Eschenbach in his telling of the legend, Parzival (approx. 1220CE). Likewise, the portrayal of the Shekinah in Card 11 her star-crossed robe offsets the otherworldly look of her visage, above her hangs a grape vine, next to her is to be seen a chequered floor. This, to the untrained eye, might seem an odd assortment of symbols, looking at it merely draws you into the mystery further, it intrigues the eye, it piques curiosity: who is this mysterious woman? What is the association of al of these symbols?

All of these responses are the essence of the Tarot, to draw form within the viewer an unconscious response that goes deep and draws upon what we have been inculcated with from the outset of pour lives, but which very few of us are called to investigate further – this is the essence of the Quest.

The Shekinah is, of course, the divine feminine. The chequered floor a telling clue where to find her – deep inside the Temple. The Grapes signify royalty, of a coming one who will seek for her, who will recognize her and who will honour her.

This is a small sample of the depth of learning that has gone into this superbly presented pack and yet it is a learning that has been applied effortlessly by the artist.

Published by Red Feather £43.19 ($34.99)

The Book of Merlin: Magic, Legend and History,

John Matthews

Amberley Publishing, Stroud. (publ. September 2020)

This is a thoroughly absorbing and engaging book that takes us on a journey through the many manifestations of this most famous of wizards or seers, through history, culture and through our own perceptions of him within the Arthurian legends.

In many of the Medaeval manuscripts Merlin appears in much the same way as the prophets appear in the Old Testament. But Merlin is far more witty and cunning and not as self-righteous as the prophets. He is much more fun and, I should say, Human – even if, as Geoffrey of Monmouth states (in The History of the Kings of Britain, c.1135) he is half man, half demon. And it makes for a splendid read.

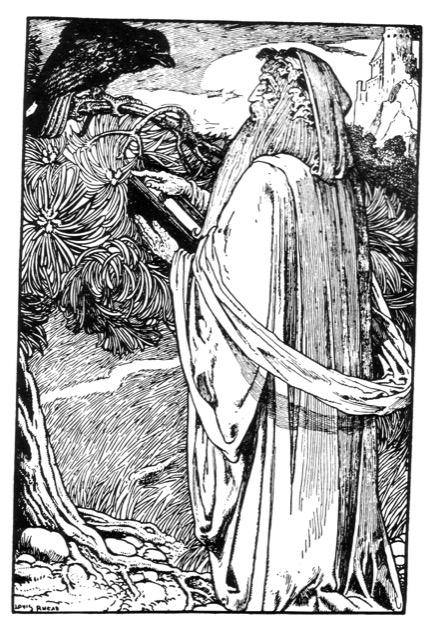

One gets the sense that Merlin serves as a kind of proto-psychologist for his day. The visual imagery associated with him is the stuff of dreams and what strikes the eye with an immediacy that is as compelling as the writing, is the Jungian quality to it. Jung saw dreams as echoes of the deep interior of our psyche and, bizarre though such dreams can seem in our everyday lives, Jung believed very firmly that they have a lot to offer us in our everyday lives, that they are communicating to us on a deeper, inner level our true identification. This is the sense we get from a reading of Merlin. And in the reading, we must also look to the illuminations that accompanied his stories through the ages: they are just as dream-like.

Geoffrey was writing in the immediate period before the Inquisition and his book was the first bestseller of its kind. But these were dangerous times and, with the benefit of hindsight, it is remarkable to see that Merlin, in these highly Orthodox times, should be described in the way he is.

In Geoffrey and also in Gerald of Wales, Merlin (Myrddin) is a wild-man of the woods called Merlin Sylvester, possibly also known as Lailoken (as recounted in the Life of the Scottish 6th century St Kentigern): he is in effect, a shaman with the ability to heal on the inner levels. This trickster-type character, is able to cross over into other levels and to co-join or to transcend barriers in order to bring about his great acts of ‘magic’. In this case we must see ‘magic; not as the conjuror’s hocus pocus but as the great proto-science that, in having been shunned and anathematized by the Church, was soon to develop in its own way beyond Church mores and eventually be realised in the work of Jung and co.

In Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur Merlin appears in the early books as an unconventionally wise man who is more often than not quite happy to play the fool in order to see that his charge, King Arthur, can learn to see wisdom. One is reminded of Nicol Williamson’s artful but compelling portrayal in Excalibur. It is telling that at the critical moment in story, the moment when Arthur is to be seen as a fully independent figure of authority over his court that Merlin should disappear – into a cave, half-willingly, by the subtle, but mysterious Nimue.

However, this is not the whole Merlin. In certain of the early texts we see Merlin as a lover, but one very much haunted by the various wars he has seen at close quarters. In our present age of polarisation, we can see perhaps more penetratingly, the look in his eyes as he unfurls his angst and his terrible visions of the future. It is perhaps one of the great tragedies of our present state of democracy that figures such as Merlin are relegated to the side-lines as figures of doubt, of fun and of ridicule – whereas those who should be ridiculed are those who cannot see beyond their own vanity for want of a Merlin style counsellor.

This is thorough survey of the Merlin material and is written to be read by all not just for a select few. The style is absorbing, engaging and speaks to the everyman in each of us as Merlin himself would have wanted it. The book is fully sourced and the plates section in the middle gives a wide breadth of Merlin imagery down through the ages. My only wish is that there was more of the Medaeval imagery of him on show, but that is a small quibble for a book that is a thoroughly entertaining read.

David Elkington

illustration from Malory’s Le Morte D’Arthur by the 19th century illustrator Aubrey Beardsley.