In blank blocked capitals above predictable blob graffiti, SHIVA precedes KARMIX RAPPEA! on the exit from Florence, 31st May 2019

Even a contrived retrospective meditation on the signalbox scrawlings above (Hindu God versus misspelt rapper duo?) can’t excuse the fast-forwarded tedium that followed. As if taking the baton from the exterior of Florence’s Santa Maria Novella station, the journey to Bologna I can safely say, was about the most boring rail journey I’ve ever done. The estimated road time is around 90 minutes. The accelerated, non-stop, electric train aims to take only 39. For those dedicated to wrecking the environment there are also planes available[i] – the fastest being operated by Air France . . . which takes 4 hours and 20 minutes with a 50 minute layover in Paris and costs £3,688 for the round trip, as opposed to £27 return by train.

If only we’d had bikes . . .

Yet it started well. The departure from Santa Maria Novella is deeply atmospheric in a dilapidated way. But not far beyond the Florence/Firenze suburbs the train enters a tunnel from which it rarely emerges. It’s like being in a speeding tube with occasional bright flashes of sunlight. Stop the world, I want to get off[ii]. In lieu of bikes, granted three extra days and a lot less luggage, I would infinitely have preferred to walk the 63 miles to Bologna. We did get the odd tantalising glimpse of countryside . . . but never enough. The outside world ceased. We could have been spiralling down towards one of Dante’s nine concentric circles: “Lasciate ogne speranza, voi ch’intrate” – Abandon all hope, you who enter here. Instead, in the reflected deadness of the tunnels, apparently inconsequential (but to me enigmatically hopeful) scenes from the day before, rescued me from burial alive.

That distant-seeming afternoon on the earth’s surface had grown blazingly hot, making my proposed ramble, over-ambitious for the children. Following separate explorations for a spell, we all met up again near the Porta San Niccolò to cross the Arno and trace another long, improvised diagonal back to the apartment. Just off the end of the bridge not far from the Torre della Zecca, we came across this flower island . . . which breathes again, stilled forever under the clouds:

Tourist drop-off point on the north bank of the Arno, Florence, May 30th 2020

All across Italy I’d been trying to improve my very poor Italian – throwing myself out of my depth in the hope that something would connect; that the branches and twigs of tenses and vocabulary would stick in my mind. Perhaps the odd cutting has taken root, but short of living in the country, this tree is never likely to produce much fruit. Increasing the problem of learning a language, is that all too often the natives of foreign lands are keener to practise your language than help you improve in theirs – which is only human nature.

If you can avoid falling into the more pointed definition of ‘tourist’ (persons with disposable income who jet to beaches for no longer guaranteed sun and indistinguishable nightlife. Or, at the other end of the spectrum, display a duty to obey guidebooks) perhaps the best thing about travel to faraway lands is the way it emphasises and redefines the sense of being an outsider; the way it questions home and not-home.

To return to my disdain for Adam Phillips’ statement in Patience (After Sebald)[iii] that “Only children have homes. Adults don’t have homes,”[iv] I realise that nowadays, my instinct of being at ‘home’ arises mostly from a feel for place – for landscapes and buildings; for an atmosphere rather than a social circle; for links and equivalences. Although travelling as a family inevitably means that some aspects of home are always present, my idea of ‘home’ has become increasingly metaphysical. I don’t know how common this is. Perhaps most adults given the opportunity, try to bury themselves in a security of home using money and material objects, friends and familiarity? Perhaps most, only want a holiday to relax or provide an agreeably brief jolt of awareness? Yet the strangeness and interest supplied by the tangible novelty of new places abroad, is always around us at home – waiting; silent; profound. If there is a ‘trick’ to appreciating life, one crucial aspect of it resides in being able to find strangeness and interest within the familiar: unexpected thoughts, a change of angle, a different level of concentration or relaxation . . .

Is a traditional sense of home partly created by taking the familiar for granted, by retreating into the sense of security that advantaged or complacent children feel? Are these the children Adam Phillips is thinking of? Maybe because he was one himself? Most are not so lucky and may temperamentally prefer holidays to be unfamiliar only within certain limits of comfort?

Even for those practiced at finding the strange within the familiar, the dislocation of travelling is bound to provide extra inspiration – and maybe, not understanding the language can extend the valuable nature of this dislocation? Adam Phillips’s statement implies that everyone is driven towards trying to reach a sense of home, to create such a feeling of safety. But perhaps we shouldn’t want this safety, pushed far enough perhaps we can do without it? Or, as with doubt and faith, perhaps what is most valuable is the tension between home and not-home?[v] As in the contradiction of ruinance[vi], perhaps it’s possible to escape through such tension, all our trivial consumer distractions, or even to get closer to the actual meaning of life itself (assuming it has one)? Is this the difference between travelling and tourism? One is trial and exploration, the other, a kind of privileged relaxation? Not that there can’t be some overlap between the two . . .

Venice improves upon acquaintance. Avoiding the central tourist zone, it recovers its appealingly shabbier reality – appealing in bright sun anyway. The sun being at its powerful zenith, for all our sakes and especially the children we had to find a park and the shade of trees. The comparatively hidden one we discovered (Parco Savorgnan) was grottier than the central wayside gardens (Giardini Papadopoli) of a few weeks earlier, but more real. It was also rich with mosquitos, which luckily didn’t seem to fancy the children. This was mine and K’s final opportunity to take it in turns to ditch the luggage and spend a couple of hours wandering in the searing, light-ghosting, heat. Our daughters were footsore and tired of what must have seemed to them, aimless roaming.

In the Parco Savorgnan the girls played happily for hours, at first with local children – the lack of a common language appearing to present no problems. Then we met a French grandmother, in Venice for the biennale, whose grandson began to play with our younger daughter. The grandmother’s English was far better than our French, and needed to be, for we had a long conversation about art, especially painting, of which she had years of colourful views and opinions. This grew into her experiences over the decades, of Paris and Venice. Within the relieving chiaroscuro of the trees, her impressions since the 1950s were mesmerising – worthy of recording, had she been willing and the equipment available. She approved that we aimed to keep our children away from the ill effects of technology[vii] for as long as possible – for it was “destroying the younger generation. Détruire!” she emphasised.

On a different park bench a little later, I found myself in conversation with Rusty – a property renovator from Los Angeles – whose daughter was playing with our elder daughter. He began by trying to fathom how the British could possibly be so stupid regarding Brexit, before switching to the Conservative party leadership election: “Boris! Surely no one will vote for Boris!?” Convinced at the time, that few would be idiotic enough to endorse Boris, and unaware of anyone who had voted “leave”, I expressed my equal dismay, before countering with: “How could the States be so stupid as to end up with Trump?!” At this point we both began to laugh. Faced with the twin lobotomy of Trump and Johnson, other than terrorism or suicide, what else can you do? Thankfully, as I revise this text, Trump is on his sulky way out – leaving us only the “shapeshifting creep” to dispense with[viii]. But that a psychotic and bigoted moron could occupy the White House was obviously a shaming embarrassment for Rusty. He began to explain the American voting system and how easily undemocratic things could be “made to” happen. Obviously, the same misdirection and corruption is rife in the U.K – even more so during this last year, accelerating in the periodic shadows of the covid distraction.

Sharing a bottle of wine lurking in my rucksack, the conversation changed to less painful topics – beginning with 60s cars. As it turned out, in days still fondly remembered, Rusty used to have a Triumph Spitfire . . .

From geography and landscape, Shropshire and Arizona, we ended up on the Angeles Crest Highway[ix] – evocative mountain road used in the filming of Donnie Darko[x]. Surprisingly, although Rusty knew that route well, the film was an unknown quantity. But then, far from its Californian locations, Donnie Darko’s cult popularity took root in England.

It could be that beyond a basic political stance and old cars, Rusty and I had little in common, yet a long conversation In English accompanied by wine, ably created the opposite impression.

Poster for the 1972 giallo, Amuck

When it came to my own sun-baked wanderings, I’d been charged with finding a cheap supermarket and eventually, more by luck than skill, discovered a Conad. Continuing north, the streets were all disconcertingly hacked off as the edge of the precarious land is reached. Vaporettos[xi] chugged away to more distant islands – such as the one inhabited by a cravat-wearing, waspish writer, Farley Granger, in the 1972 giallo, Alla Ricerca del Piacere, or to cite its English-language title, Amuck[xii] (what was wrong with the more literal translation of In Search of Pleasure? I wonder). Though it’s good to see Granger and (typically) rather more of Barbara Bouchet and Rosalba Neri, Amuck is far better for its locations and atmosphere than for anything else. Forty-seven years later, apart from the wash from boats, the Adriatic was as mirror calm as it is in Alla Ricerca del Piacere, and I considered how much more vulnerable Venice and its islands must feel in a storm.

Circling back, I sat on a semi-circular dais of steps that disappeared into the dazzling water overlooking the lagoon, watching a continual stream of trains – arrivals and departures – navigate the causeway. With boats of all shapes and sizes frequently passing, and aeroplanes landing and taking off in the distance, it was reminiscent of a children’s picture-book – all that old atmosphere of hope, when even planes seemed happy and exciting and travel a beckoning and harmless pleasure. The truth is that excessive faith in science and technology – those oversized pair of blinkers – has turned us into demanding children. Driven by the fraud of market economics, our blind greed for endless ‘progress’ opened the door to the mess we are in. But as the chameleonic shifts and sleights of hand in art[xiii], are dependent upon some eternal quality preceding them, clearly there was some good in the original idea of progress – before its ideal twisted into fevered belief. At present, whatever the founding cornerstone was, we have buried its lustre. We need to change down several gears and find a better currency, a far less wasteful space . . .

Venice 31st May 2019

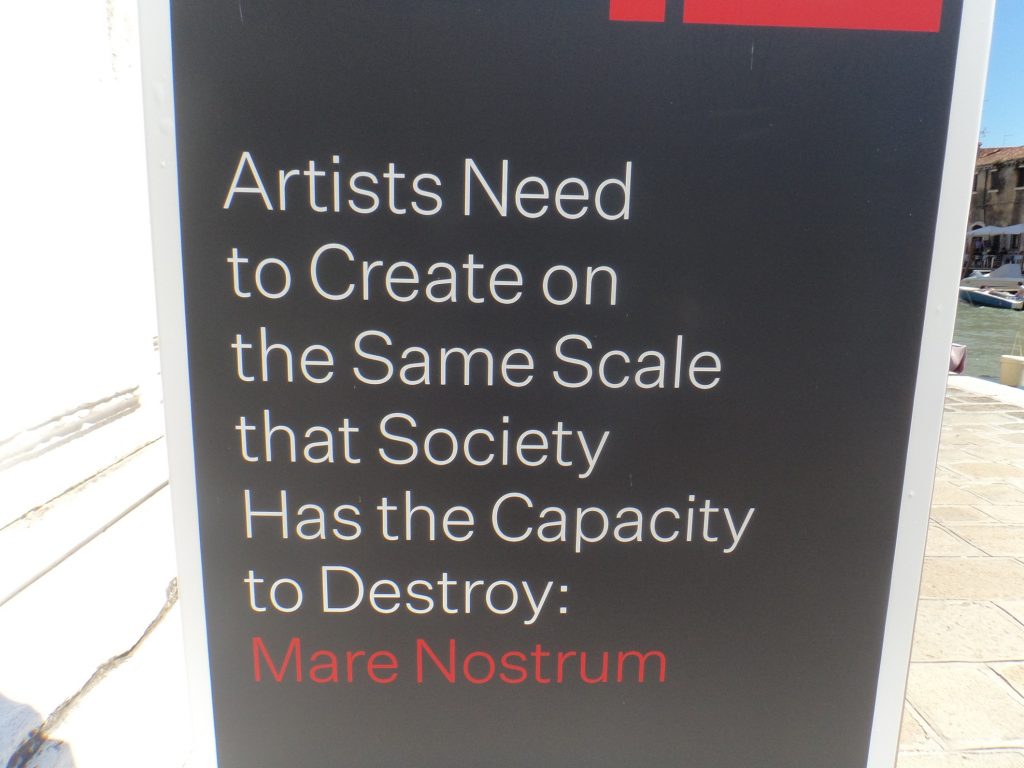

With so much ‘art’ fawning on Society, at least some of the Biennale installations[xiv] curated under Mare Nostrum[xv] had a worthy objective, even if, concerning the manifesto stated on the billboard above, we are on a hiding to nothing. Aspects of Mare Nostrum’s installation, anticipated my more recent viewing of Patricio Guzmán’s admirable documentary films – mystical and horrific by turns – Nostalgia for the Light (2010)[xvi] and The Pearl Button (2015)[xvii]. While the mystical side of both films is occasionally sentimental, in the light of the horror of Pinochet’s regime this is justifiable. More negligent is the way that Nostalgia for the Light brushes over the negative impact on the world of Science. Similar to the encyclopaedias of transport by land, sea and air, and the concomitant globetrotting hopes of children, Nostalgia for the Light goes back to the ideal wonder in most of us. But while mystical or metaphysical star-gazing is intuitively and inexplicably worthwhile, the application of it, the calcium maps of stars etc, the attempts to make it mean something logical, are as tragically pathetic as the 70-year-old woman’s quest to find the whole body of her ‘disappeared’ husband. You can feel for her desperation to achieve this before she dies, but that doesn’t stop it from being as futile as thinking that we can find serious answers to our existence by looking at the stars. We will inevitably find all kinds of ‘evidence’; we may find metaphysical reassurance; but answers will always be beyond conscious understanding. Scientific research, whenever pertinent, due to the power of those that fund it, cannot help but tend towards ‘profitable’ applications – i.e. destructive[xviii].

Venice in a half heat-haze sepia 31st May 2019

I can’t be sure now what hour we caught the Thello at Venice, since the times recorded by the camera were stuck on some British double-wintertime at least 2 hours out of sync. All I remember is that as we drew across the causeway towards Venezia Mestre[xix], a minor nosebleed forced our younger to stop talking. As she’d been obsessing about nuns and fishmongers and repeating the idea that she wanted to be a beggar, the enforced silence was probably a good thing, especially for her. Somehow, she’d gained the impression that beggars simply relax in the street for a while, before shuffling to outside cafes nearby for a slap-up meal on their proceeds. Peculiar the rubbish that people of all ages earnestly believe. I wondered how different our impressions of Venice, Italy and of travelling would be if we had the money to stay in luxury hotels, travel by the Orient Express and have great conversations to cordon bleu dining the whole way? Or enjoy one of those endless parties which always look so appealing in films but would probably be mind-numbing after twenty minutes: New Year’s Eve extravaganzas with everyone in bizarre costumes and people getting bumped off every few stations down the line. I’m thinking of crumby but sometimes enjoyable films such as Murder on the Orient Express or 1964’s Night Train to Paris – which we’ve often watched on New Year’s Eve just because that’s when it supposedly takes place and the TV (when we had it) was unbearable.

April is curious about the work of crazed artist Adam Sorg in Color Me Blood Red (1965)

Perhaps the thought of joke art, my daughter’s nosebleed, crumby films and a soporific memory of a forgotten sandy shore with wispy trees, reminded me of Herschell Gordon Lewis’s Color Me Blood Red[xx]? This 1965 film has a strong feel of the period, especially regarding interiors, but as recently rediscovered, isn’t worth watching at normal speed – despite Gordon Oas-Heim as tortured artist Adam Sorg and the amusing art critic and gallery scenes. Much of the film is set on the beach (Sarasota, Florida, according to IMDb) and within the madman ’s wooden house – which looks as vulnerable to the slightest heave of the ocean as Venice. Being an artist (all maniacs of course, and as objective towards the flesh as doctors!), Sorg is too obsessed to notice April, the bathing beauty in a pink bubbly bikini, except as a potential source of blood for his canvases. The actress playing April was in real life, Candi Conder – and few names could be more apt for her role. This aspect of exploitation films, the manipulation of the sex or lust drive, might be worthy of a Digression itself, since, just as a wide view of a landscape with an enticing prospect is somehow more than the foreground, the horizon or the journey between[xxi], so the biological drives, surely, hopefully, contain other less basic, less visible qualities? Whether or not one could love the character of April – who, as the film manipulates her, appears shallow, even stupid – is probably beside the point. She is intended for a pin up, literal Candi for the eyes, naïve but essentially good, and destined in time (as is the implication behind even the wildest 60s films, ‘free love’ being reserved mainly for men[xxii]) to become the perfect housewife. Obviously, she is very ‘sexy’ in a late 50s way – the 50s lingering here, as most decades do, until at least the middle of the following one. It might have been 1965, but this is a film absurdly, parodically, about the ‘Beat’ generation. But to get back to Candi Conder: the ‘straight’ male gaze – could watch her walk up the beach (as the camera does lasciviously) to her encounter with nutter Adam Sorg and his easel, many times. But, be we straight, gay or bisexual, do such pleasures, ever get us anywhere? What is the hidden value or are they just animal leftovers? It’s true that mild titillation, may suggest or illustrate the greater danger of porn for driving addicts towards futile obsession. Taken philosophically, pornography also graphically illustrates the unsatisfiable nature of sexual desire. Would it be different if you loved April? Does love or beauty balance lust, as physical journeys across landscapes may balance the desire for what lies inside or beyond them? Can religious or metaphysical feeling likewise balance a desire for meaning? Where is the equilibrium between the valid and the distraction, the challenge and the rote? Or is the constant aspiration of desire in a world that can never be enough, always, in whatever form, unbalancing? For desire (like hope) almost always remains or revives beyond its objects, be they landscapes, people or ambitions . . . and anyone who can manage to escape discontent; anyone who is fully satisfied by religion, sex, country walks, (or by far less: sport; TV; drugs; technology, etcetera), is self-deceived . . . or perhaps, has become (neatly, correctly) habituated to some lesser human sphere. Are even those who believe in a love too over defined – fixated entirely in particular persons – equally mislead?

Critic salutes mad artist at private view – not a situation I often experienced!

Anyway, despite its axe-heavy satire, its humour, the cars, backgrounds and hilariously bad art (though one of Adam Sorg’s less dwelt-upon paintings, at least from a distance, has something more intriguing than anything I happened to catch at the Venice biennale), Color Me Blood Red is fairly tedious. Its beach frolics and hip talk require a lot of fast-forwarding. Plus, I’ve never seen the point of gore (another animal leftover?), no matter how real – or in this case pathetic. Corman’s, A Bucket of Blood (1959)[xxiii] with its brilliant script[xxiv] (highlights spoken by poet Maxwell Brock: “Life is an obscure hobo, bumming a ride on the omnibus of art.” Or: “The artist IS; all others ARE NOT.” Or: “Walter has a clear mind; one day something will enter it, feel lonely and leave again.”) is superior in almost every way. Yet surly Sorg is both more dangerously insular and funnier to me than Dick Miller’s likeable Walter Paisley in the earlier black and white, cult classic . . . maybe because Sorg is so reminiscent of a long-gone friend? Are all artists unbalanced? K maintains that “they obviously are” indisputably including me in her classification[xxv]: “If an artist can achieve balance, they become a craftsperson.” Or a formula perhaps? I’m sure Adam Sorg would agree . . . and sign the contract in blood.

Darkness fell on board the Thello somewhere between Padova and Verona, and soon afterwards we turned our chairs into beds. By the time we reached Milano Centrale[xxvi] the children and K were asleep or pretending to be and I’d left the compartment for the corridor, to film the incredible signal boxes and our arrival. Whether or not it remains the largest station in Europe “by volume”, some claim it is “still the most pompous”[xxvii] – dubious details including a swastika created for a possible visit by Adolf Hitler, inset in a section of parquet floor.

Arriving at Milan, 31st May or 1st June 2019

Milan being the only other place where passengers can join the train, a long wait ensued, not all of which was scheduled. Refusing to surrender to her obvious irritation and noting my interest in the architecture, the tall, elegant guard indicated that I could get off the train and wander about if I wished. We would be delayed for some time.

At about what our camera claimed was 3 A.M., a wobbling light in the distance resolved itself into a man cycling down the epic platform. He had come to perform the uncoupling – a different locomotive being required for the climb into the Alps. I hung about to watch him at work. Stepping back onto the platform as the locomotive drew away, the ‘conversation’ that began between us was hopelessly comic. Since his attempts at English were accompanied by expressive gesticulations, it naturally encouraged me to add emphatic gestures to my attempts at Italian. Managing to say that I worked (lavoro was one word I did remember) on old steam trains[xxviii] (vecchi treni a vapore – though I think I just made puffing noises for the last bit), he became even friendlier. To him this made us colleagues, brothers under the camouflage of overalls and cameras. Enthusiastically, he began to pat me on the back and shake my hand and was about to invite me down onto the track to help couple up the replacement locomotive. Familiar with both English and continental style couplings, I would’ve been pleased to lend a hand, but unfortunately, just then, a superior inspector-type turned up and the division of ranks between him, the shunter and the driver of the replacement locomotive – who’d just happily thrown himself into the melee of our conversation – broke up our footplateman’s comradeship. Then the guard returned looking unbearably contained and exasperated by all of us and I felt obliged to get back on the train – just when I thought I might be offered a cab ride over the Alps to Modane.

31st May or 1st June 2019

Another delay followed, during which both shunter and driver disappeared. Later still, the long overdue connecting train from Rome arrived and the ire of the guard began to accelerate. Before Milan, she’d watched me filming the disappearing rails through the small corridor end window with indulgence and a forced smile; now, she appeared almost desperate to confide. Presumably influenced by my passport (which the guards keep and return near the end of the journey) she tried German at first, switching with no avail to Italian and then French – in all of which, she sounded enviably fluent. Finally realising I was English, the reasons for her tetchiness all came out. Some were directed towards Thello management, “lots of mistakes here” she kept muttering, as well as expressing scorn towards recent timetabling “all gone awry”. Awry was the untypical word she was drawn to repeat. But what agitated her most was that it was the “first day of summer . . . and I feel fed-up on this job”. After three years it “had gone awry. Not so good anymore – the constante shuttling”. Originally Austrian, she’d enjoyed living in Paris and Dijon”, but felt “sick of its whole way of life”. Fuelling her despair was the plain fact that the train had been over-booked, which had “never happened before. Never!” Excess numbers of passengers were clambering aboard expecting berths already taken. Everything was awry. Starting to think she would walk off the train and disappear into the Milanese night, I tried to be sympathetic. Without warning, she took a dramatic deep breath. Releasing and then pushing her long hair back, she reformed it tightly into its bunch with an unconvincing laugh. Grasping my arm very tightly (she left a handprint) she regained her official hauteur and adopting a grim smile, went off down the corridor. As I was – inevitably – awake all night, I did see her a few more times. She had a small room at the end of the corridor – which she was not allowed to offer to passengers – and lay down on its narrow bunk once or twice. Wedging the door open she occasionally looked up and spoke if I was around, but these sentences never turned into a conversation, maybe because her English was less fluent than her other languages? Jumping hours forward in time, I remember the moment in the corridor as the train drew into Paris. She returned our passports and for a moment looked as though she might embrace me. Or had I become just another traveller? Unsettling to think of all those people you feel fleetingly close to, who you will never meet again. She smiled but might have been embarrassed. Loaded with bags in a suddenly crowded corridor, did I act too distantly? Occasionally I’ve felt guilty about those claustrophobic minutes. I always imagine I look approachable and friendly, but K says I often look fierce.

Returning to the preceding night in Milan, presumably I looked friendly enough to the Japanese man, possibly a musician, who was last to board the train. Climbing down to help him with his mountain of luggage, it took two of us to lift one suitcase. This black vinyl object with wheels was so heavy that I wondered if it was loaded with gold bars . . . but thought it better not to ask.

Eventually we were rocking towards Turin. Sadly, as on the outward journey, the mountain section was all at night. With eyes propped open by metaphorical cocktail sticks, I strained to pick up as much detail as possible in sporadic moonlight and the glint from rushing rivers and snow . . . sublime in a mournful rather than uplifting sense, unless that was just my weariness.

As before, I was very impressed by the environs of Modane[xxix] – hauntingly evocative border place in the dark and silver mountains. By the solid stone station extensive sidings and yards extended to the river which before and after the town often rushes fiercely in a channel abruptly beside the tracks.

As before[xxx], the locomotive exchange under the defensive stare of the sinister signal box – from Italian to French voltage – was not done with any haste, especially since we awaited the southbound Thello for continued passage. I imagined a fantasy life as a train driver in Modane. A short story perhaps? Or seen through the eyes of the disgruntled, young woman guard – that tough air hostess on rails! This went so far as envisaging an angular daily walk from a small slanting apartment across the channelled meltwater from the locomotive sheds. Then I got side-tracked by the style of the footbridge over the cascade and distracted by an echo of Nietzsche . . .

Front of passing electric, north of Dijon, a frozen frame from a piece of film. Sunrise 1/06/2019. Our passing speed must have been well in excess of 150mph. Note the CONAD bag in reverse.

The pre-dawn in France was misty and calm, the sunrise intense. It flamed through trees and woods and occasional grain silos. After the rushing station of Bourg-de-something (too fast to read) the landscape became serene again. Acres and acres of wide, beautiful cornfields, rivers with pockets of mist . . . reminding me of some idealised and radically depopulated section of the outer home counties. We drew to a halt in silent Dijon well-ahead of any kind of rush hour. After a leisurely start onward to Gare du Lantenay, the train accelerated steadily before going berserk, striving to make up all the lost time. Only as the outskirts of Paris began to gather were the brakes ever used.

Halted just beyond the platforms at the Gare de Lyon, our time available to walk across the city was diminishing. We finally rolled to a stop virtually the whole length of the train from the hydraulic buffers with just above an hour to spare and set off at a furious walking pace towards the Seine. Over the Pont d’Austerlitz we followed the river, eventually passing the bookstalls so often used in films – from small Parisian productions to Hollywood epics such as The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1962)[xxxi]. Re-crossing the Seine the unfortunate Notre Dame loomed up on our left. Regaining the north bank via the Pont au Change (“landmark bridge and popular photo op”), we headed up the Boulevard de Sébastopol, discarding all traces of leisureliness.

We were supposed to allow an hour for customs and check-in at the Gare du Nord’s Eurostar terminal, but with nothing to declare, despite queues, had little trouble with the former. Passport control involved an English border post weirdly out on a limb. Recognising immediately by speech that we both originated from London, the passport official asked about our unusual surname and got the usual potted history. “Anglo-Saxon through and through then!” he said approvingly, and to this day I’m not sure if he was just being friendly – welcoming me back to dear old Blighty (on a limb) – or whether there was some xenophobic undertone. Was he sounding me out (to be contacted later) for BNP[xxxii] membership?

The Eurostar left on time and a display screen near us, at two different points when I happened to glance up, registered 297 kph – which approximates to 184 mph. I was suitably impressed. Only my old dark purple marvel (bicycle), once (apparently) did better – attaining 687 mph on the Honiton Bypass[xxxiii] during the summer of 1989.

After weeks of travelling, was my fantasy that the perfect home would be a self-contained railway carriage attached to various trains – berthed in the marshalling yards or rural sidings of different countries whenever I preferred to stay and explore – beginning to pall? Or was the gravitational pull of the habit of ‘home’ lowering the tone? Perhaps Adam Phillips was half right after all? I’m not sure it’s possible to answer such questions. These final sentences come eighteen months later, and it could be that as with most journeys, the real travel is within – where whatever true home we may have, is located anyway. As for the tunnel under the Channel, fortunately, our youngest daughter was no longer concerned about sharks getting in through the windows, while I shut my eyes and ears and thought myself outside.

© Lawrence Freiesleben,

Cumbria, July-November 2020

NOTES

[i] Accessed 17th July 2020: https://www.google.com/flights?q=florence+to+bologna+by+air&source=lnms&impression_in_search=true&mode_promoted=true&tbm=flm&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwirjbjQ89PqAhWkUhUIHS4UD_EQ_AUoAXoECAwQAw#flt=/m/031y2./m/096g3.2020-08-02*/m/096g3./m/031y2.2020-08-06;c:GBP;e:1;sd:1;t:f

[ii] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stop_the_World_%E2%80%93_I_Want_to_Get_Off

[iii] https://www.imdb.com/title/tt2118702/

[iv] http://internationaltimes.it/the-italian-digression-part-8/ See Note 4

[v] The main reason I remain so deeply affected by Jerzy Skolimowski’s film, The Shout, (1978), is that its landscapes and villages capture the exact air I encountered at 18 on moving to an isolated caravan, of the remote strangeness of North Devon. Nowadays, I would have to shift to a Pacific island or the moon, to equal such a dislocation . . . The lanes, cliffs and dunes used as locations were all places I came to know shortly after it was made, without my knowing the film existed. Although the story itself remains hypnotic and the standards of décor and appearance so much more appealing than those of the stultifying present, at the same time, part of my mind bypasses the characters and all the background hints and suggestions of the scenario, to recognise my most powerful sense of geographical attachment – to North Devon 40 years ago: maybe the first time I saw a landscape with separated eyes and mind, away from the influence of friends or relatives? Although many of those landscapes haven’t changed so much, clearly the whole social atmosphere of the late 70s has vanished. In this sense Adam Philipps is correct: the original homes of adults are inevitably lost in the past – in a childhood which for most perhaps can only be perceived (or imagined) retrospectively? In the long run the concept of home cannot be trusted. If you cannot restructure its basis, you end up constantly yearning for the past. For me, as the perfect example of this, the superlative W G Hoskins television series, Landscapes of England https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Landscapes_of_England may also be a perfect catalyst? Almost every episode sets off a powerful longing for the 70s. Every episode underlines the increased avarice of the Western present.

[vi] To use a rather dubious biological metaphor, the contemplation of ruinance [see Note 2 of http://internationaltimes.it/the-italian-digression-part-8/ ] is another of those stimulations/irritations which can work as a kind of mental antibody, the production of which in the form of ‘overwhelm’, contradicts any potential negativity – even if negativity wasn’t intended.

[vii] See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xNgQOHwsIbg – particularly the section on the addictive danger of cell phones etc., from 3.10 onwards.

[viii] Former Obama press aide Tommy Vietor’s description of Boris Johnson: https://www.thelondoneconomic.com/politics/biden-ally-lashes-out-at-shapeshifting-creep-johnsons-racist-comments/08/11/

[ix] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Angeles_Crest_Highway

[x] http://internationaltimes.it/donnie-darko-a-digression-on-universality-and-inevitable-nostalgia/

[xi] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vaporetto

[xii] https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0068206/?ref_=fn_al_tt_1

[xiii] Flashy facades and conjuring tricks that may nevertheless reinvigorate what we already know.

[xiv] Although much of the Biennale merely showcased third-rate art from around the world, art “barely worth domestic consumption, let alone export” at least it was (generally) free to view. All great/true art galleries should have free admission . . . but then not much of it is great or true!

[xv] https://www.itsliquid.com/mare-nostrum.html

[xvi] https://www.imdb.com/title/tt1556190/?ref_=fn_al_tt_1

[xvii] https://www.imdb.com/title/tt4377864/?ref_=nv_sr_srsg_0

[xviii] Just as art is corrupted by the desire for profit and/or entertainment.

[xix] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Venezia_Mestre_railway_station

[xx] https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0059044/?ref_=nm_flmg_dr_26

[xxi] “You can never know how it [such a landscape] possesses what it does. It’s not in the uncertain distances nor the bright foregrounds, nor quite in the journeys in-between . . .” as Huw says in Estuary and Shadow – and I’m sure I’ve repeated all over the place.]

[xxii] When Julie Christie behaves in the way of men in the overrated yet nevertheless worthwhile Darling (1965), typically she is judged far more harshly – not for her character’s undeniably shallow nature but for her fashionable lack of morality. Italian directors did this type of film so much better – either at the abstract end of the spectrum (Antonioni) or the more accessibly satirical end, for example La Dolce Vita (1960), Dino Risi’s Il Sorpasso (1962, see part 4 of this Digression) or Pietrangeli’s I Knew Her Well (1965: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0060545/?ref_=nv_sr_srsg_0 ). Darling, looks dated in a far more disabling way than any of these films.

[xxiii] https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0052655/

[xxiv] https://cafedissensusblog.com/2018/08/15/roger-cormans-a-bucket-of-blood-i-will-talk-to-you-of-art/#

[xxv] Discussing creativity and the ‘artist’ more than a year ago, K saw creativity as a factor common to many people “most of whom have no need for high ideals. It need be no more than an activity they enjoy – a craft or a hobby: painting, modelling, gardening, cooking . . .” The trouble with artists, in whatever medium, she claims, is that they “like to inflict themselves upon everyone.” This made me laugh, yet I know what she means. Whatever justification ‘artists’ might come up with: childhood trauma; spiritual, ecological or political vocation; an urge to redirect or save the planet; imaginative overload; inspiration; the sensation of being no more than a conduit . . . whatever excuse or reason surfaces, in most cases, to inflict their results on others is an inescapable part of the process, personal ego or ambition, two of the bad faith aspects hard to avoid. K feels that people could live without art but not without creativity. But is it only a lack of self-confidence or self-esteem that prevents certain creative people from stumbling upon high ideals? Alternatively, is it only an excess of confidence, arrogance or death anxiety that turns the creative person into an ‘artist?’ Once your imagination has been stoked enough perhaps you can live without art – especially as much of what is so classified is merely feeble diversion, repetition or copying. I was pretty well stoked by the age of twenty, but still need new coal to burn now and then (and the carbon metaphor is deliberate, for excess indulgent and empty ‘art’, especially of the mainstream type, is a waste product that undoubtably pollutes our social environment). Another worrying question is whether, rather than encouraging an expansion, the internet has caused an inflation of creativity. Does the distancing from any kind of widely shared culture, simply undermine society, or could it destabilise it in a potentially worthwhile way? In a metaphysical sense, rather than being selfish or solipsistic, this retreat inside ourselves, might have aspects that should be encouraged – trying to break the materialistic dominance of time and space for example . . . but even if we are or could have been moving towards some unforeseen transformative stage, it appears increasingly likely to be cancelled. It’s impossible to see how our craven submission to every form of destructive consumerism, can now be turned back. We have invented and invested in disaster. The human race is in an error state. We’ve been taken over by our tools and can’t turn back. Short of a plague infinitely more serious than covid or a natural catastrophe rather less severe than the one on the horizon, there’s no chance of returning to some previous ideal – there are simply too many of us . . . and no reasonable, political system can deal with this simple fact.

[xxvi] https://railwaywondersoftheworld.com/milan-central.html or

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Milano_Centrale_railway_station

[xxvii] https://retours.eu/en/29-milano-centrale/#

[xxviii] For a few years, I was a trainee driver on the North York Moors Railway – starting by lighting up the fires in steam locomotives at 5 a.m. ready for the day’s work with occasional footplate turns learning the route, shovelling coal, observing signals and so on.

[xxix] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Modane

[xxx] http://internationaltimes.it/the-italian-digression-part-1/

[xxxi] https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0054890/?ref_=nv_sr_srsg_0

[xxxii] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_National_Party

[xxxiii] http://internationaltimes.it/cycling-at-light-speed/