We live in an age of turbulence, of increasing change, one that seems more often inflicted rather than democratized, wherein the great forces of our day are seen as no longer benevolent, but as an old-fashioned elite increasingly behind the times, Canute-like, trying to hold back the tide – in their own favour, but using political weapons that are rapidly out of date. Censorship is foremost amongst them.

In our age Science has become God: with an arrogance that makes it look all too similar to the institution it replaced – the Church. There’s an old saying in the West of England: ‘What comes around goes around’.

And now, in these Covid anxious days, the whole rotten edifice has been exposed as corrupt, incompetent and inept. Is this a sign that the entire compost heap is about to collapse?

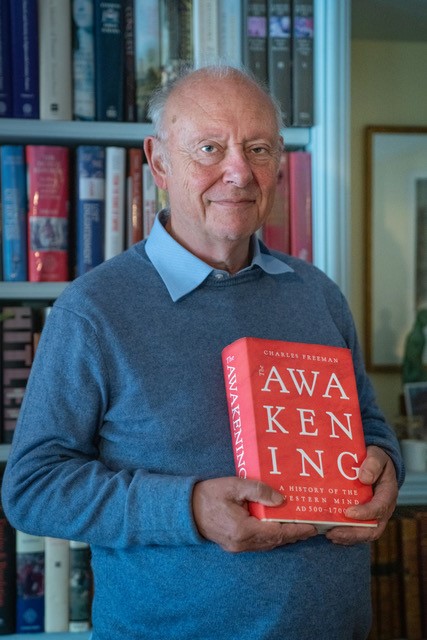

In Awakening: A History of the Western Mind AD 500 – 1700 (Published by Head of Zeus, £40) Charles Freeman chronicles another similar breakdown and the emergence from it of a new confidence, of a new thinking that was soon to leave the Church behind, no longer setting the agenda but following it. His starting point is the great intellectual shutdown enforced by Church Doctrine in the aftermath of the great Council of Nicaea in 325AD; a shutdown that was as severe as anything we are beginning to see today. Others have already written about the destruction of the classical but ‘pagan’ temples, followed soon after by the expunging of certain types of thinking, creating in its place a kind of groupthink of its day that so limited the expansion of human creativity, and thus the ability to help us to rise beyond our limitations. It is as if the Church was intent on using logic to limit our appreciation of the world rather than as a tool for enhanced understanding. The Church was actively following a policy of non-enlightenment.

If all of this seems familiar then what has gone around has come around.

Here we are again – and this is a very timely book and, I might say, an excellently written and produced book at that. It is beautifully illustrated to the degree wherein it actually is very easy on the eye and thus increases the ease of reading. Not that such ease is needed. Freeman is a good host, a superb narrator and tells his story with aplomb.

He is also direct. He doesn’t beat about the bush. For, from the outset we know what the cause is and he makes it plain: The Church.

However, he is not a scathing anti-Christian. He is a good impartial observer of the heart of the problem – and, as these pages will tell you – it is all too human. I particularly loved the chapter (5) about Abelard, the lover of Heloise, and his battles against the more entrenched orthodoxies of St Bernard of Clairvaux. What stands out most from the battle is the fact that Abelard represented in person the new force rising within the sap of the European cultural tree: he was a logician and yet, his battle against accusations of heresy from the likes of the well-connected, and ever political, St Bernard was doomed to be a loss that won the war. St Bernard, the great influencer of his day, a passionate yet remarkable voice (he was called Mellifluous ‘The Honey-tongued’) represented the old order. The great reformer of the Cistercian movement, the ‘eminence grise’ behind three of the Popes and the moral guardian of the order of the Temple. His death came in 1153 – and his influence was rapidly to wane in its aftermath.

Freeman’s elegant prose and prose style are a treat for the mind and the accompanying illuminations are a treat for the eye. I say ‘illuminations’ because that is exactly the purpose they serve. They go beyond mere pictures to insert themselves into the visual sense that accompanies any reading of history in order to make it a 3D experience. This is a highly engrossing tome and I cannot recommend it more highly.

The indelible problem about living in an age of crisis is that the mundane always comes to the fore. It is only at the true point of transformation that we begin to see the presence of magic, or so it seems. In shamanism the true magic shines through at the moment of crisis, the fever is brought to a head and then, at the moment of passing what seems dark turns to light. The British Isles have known a lot of crisis and its mythology has acted in a shamanistic vein: the point being that the myth is always there and has always influenced us at the critical time, be it the lonely stand during the early days of World War II against an utterly ruthless enemy or in the present cultural battle to see our traditions and myth survive, perhaps reshaped and reformed but there nonetheless.

This is the essence of The Magical History of Britain by Martin Wall (Amberley, £20). He contends that our myth is as abiding as a blue vein through cheese – and he is right. We’re talking here of myths that have persisted since before the days of the Druids and culminated in the Arthurian myths and the Glastonbury legends.

His is an easy read and within his story he wonderfully evokes the romance of myth but without the sentiment that can so often take us into cloud cuckoo land, thus removing the essential layer of reality. I particularly enjoyed the section on the Pelagian controversy. For those of you unfamiliar with Pelagius, he represented that ability, all too-present in the British and the Irish to challenge Orthodoxy. Pelagius is a fascinating character and what happened to him when he began to spread his scepticism over the idea of original sin was merely a taste of things to come. But Pelagius played his part in the British mythology, becoming a part of it himself, described by St Jerome, the 4th Century translator of the Vulgate Bible, as ‘a fat hound weighed down by Scotch porridge’. As Wall observes for Scotch read Irish – the Scotti at this time period lived in Ireland. This comment tells us that Pelagius was stubborn in his refusal to ‘abandon the time-honoured beliefs of his ancestors which brought him into conflict with the Catholic establishment.’ This is a highly engrossing book. I have a few quibbles but they are very minor historical inaccuracies, but not enough to hinder the overall argument. As Robert Plant says on the cover: ‘…and inspiration from the heart of the Shire.’

In The Decline of Magic: Britain in the Enlightenment by Michael Hunter (Yale £25) A challenge is laid down: did science displace the idea of magic in early modern Britain or was it the freethinkers?

In this odyssey about the march away from superstition, for that is what is really meant here by the term magic: ghosts, demons, apparitions and fairies, we are treated to the whole panoply. Whereas in the previous book magic is that which underlies the very ethos of the nation and its inherent myth, here we can see all too readily the decline of myth from the assault upon it of doctrinal Christianity – the most superstitious of religions in medaeval Britain.

The conflict represented here is the relationship between God and the natural world. It was an argument of great intensity in the medaeval period and remained so in the run up to the Enlightenment. What Hunter points out is that the challenge to the prevailing orthodoxy did not come from the early Royal Society, primarily because it too was divided on the issue. The true pioneers of scepticism were the humanist free thinkers. From them sprang a gradual and cultural osmosis based on the legacy of classical antiquity, which surviving into the era of Francis Bacon, whose strictures, when applied later by the likes of Robert Boyle, helped to lay the foundation for modern empirical science.

It is in juxtaposition of the events if today that one should read this volume. We are living in an age of increasing superstition, one governed by a kind of state sponsored terror over the spread of Covid wherein the lack of impartial information about what is truly going on adds to the overall effect of paranoia and fear. We are also inhabited by a groupthink generation who would do well to look at this book and ask how the Enlightenment came around.

This book casts a different angle on a subject covered in 1971 by Prof Keith Thomas in Religion and the Decline of Magic. It is a thoroughly engrossing tome and very compelling. Hunter, who is Emeritus Professor of History at Birkbeck, University of London knows his subject well and takes us on an entertaining journey through the extraordinary transformation of 16 -18th century Britain and the all-important founding of the Royal Society.

Science may have replaced religion but the magic never really went away: science can be magical – for to approach it in the way of a true pioneer, it needs to be approached with a sense of awe, of wonder – and if this is not magical then what is?

David Elkington