London, Patrick Keiller (Fuel)

Landscape and Subjectivity in the Work of Patrick Keiller, W.G. Sebald and Iain Sinclair, David Anderson (OUP)

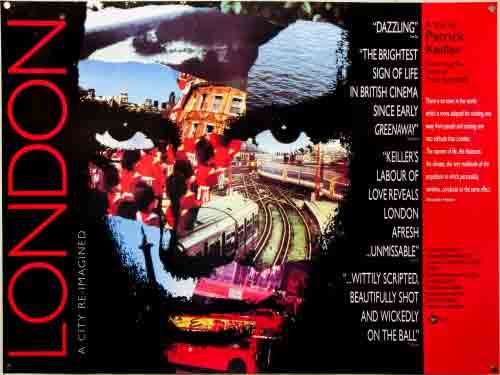

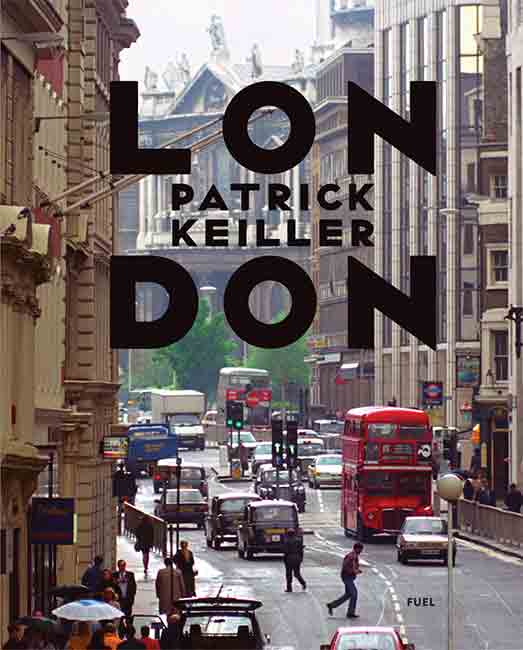

Keiller’s London film is over 25 years old now, and turned out to be the first in a trilogy that featured the absent Robinson. London the book cannot recreate the often elegiac tone of the book, because it lacks duration: we no longer watch the framed movement taken by a still camera. But the entire script, or monologue, is here, and one thing it does do is foreground the humour, something often missed on a first few viewings. Fuel have done a great production job on London, with superb colour reproductions, plenty of space and many full page photographs.

London is a film about ‘the problem of London’, and suggests that those who inhabit the city are restless, displaced, long to be elsewhere but choose to stay in a humdrum business of work and travel. They are also willing to vote in those who hurt them the most: London shows the Tories returning to power for a fourth time in 1987 despite the (now all too familiar) opinion polls suggesting otherwise in advance. It is also a year of bombings, strikes and demonstrations. In one way this seems like history, in another it seems nothing has changed except fashion and the cost of things.

For many years I used Keiller’s film as part of my Creative Non-Fiction module. I watched the film in class with my students, aware that it is not a quickly or easily appreciated film, and benefits from being paid attention to. Sitting together in a darkened room, phones switched off, watching a large screen, allowed distractions to fall away and my captive audience to enter the mood. Many readily admitted they wouldn’t have stayed engaged if they had been asked to watch it at home on their laptops; some were aghast that I had seen the film 20 times or more.

But it would often work its magic and enable those in the room to see things such as the patterns of rain in puddles, bonfire flames against the sky or the colour of the Thames anew, and be shown an older city, reveal recent historical events they did not know about (the bombings) and introduce them to another way of telling a story or stories. We would later compare and contrast it with Iain Sinclair’s ‘Nicholas Hawksmoor his Churches’ (part of Lud Heat), an occult fiction based in the apparent fact of architect Hawksmoor building churches that aligned with each other and drew on Egyptian cosmology and numerology. Presented as an essay, it is basically mystical hokum, but contains a wealth of truths amongst the author’s conjecture, and the piece has an ability to scare and startle the reader as it conjectures a darker side of London.

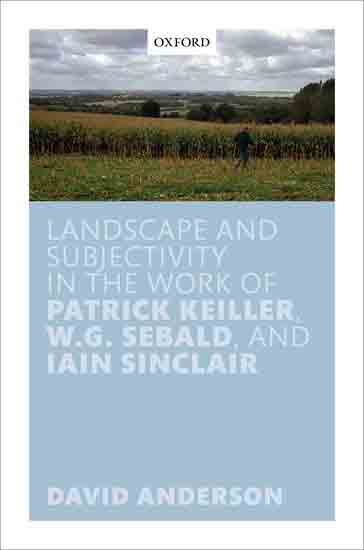

A third person who often gets linked to these pair is W.G. Sebald (for a while it was sometimes Patrick Wright, author of A Journey Through Ruins, and maker of a TV series about the Thames), and David Anderson’s Landscape and Subjectivity in the Work of Patrick Keiller, W.G. Sebald and Iain Sinclair does just that. Although all three artistes are considered in depth, they are in the main dealt with separately here, although clear thematic links are established between them.

The first chapter deals with Keiller’s early films and writings, contextualising him within the works of others at the London Film-Makers’ Co-operative, surrealist influences, and Keiller’s (and others’*) exploration and critique of space. Chapter 2 moves to the Robinson films, and is at its best when it discusses – at different times – nostalgia, the transformation of space, decay, dwelling, and estrangement. It’s readable, well thought out critical writing.

I find the discussion of Sebald less convincing, but that may be because it has taken me a long time to be able to read Sebald, and I am still unsure of how (or why) to read him. Anderson is keen, like many others, to write about Sebald’s work in terms of Britain and Europe, of post-WW2 culture and social mobility and influence. Notions of place, translation (in its widest sense), memory and myth are discussed, but I wanted more about the fictional nature of Sebald’s writing: like much of Sinclair’s work Sebald’s writing is a hybrid of fact and fiction assembled or intuited from diverse sources, resources and the imagination.

The chapters on Sinclair are thorough, informative and enjoyable reading, but they follow well-trodden critical paths and basically re-iterate previously established ways of understanding Sinclair’s use of place, image, the occult and psychogeographical conjecture. Anderson is over-reliant on working through Sinclair’s subjects (Jack the Ripper, the Thames estuary, the Millennium Dome, Bluewater shopping centre, the M25) rather than stepping back and trying to find a wider understanding of and motivation for Sinclair’s methodologies and processes of both research and writing.

These are, however, both books I am glad to place on my shelves. London is a long overdue publication, and anything that draws attention to Keiller’s Robinson film trilogy is welcome, including Anderson’s critical volume. Sinclair may have had his moment of fame and popularity, but he is not out of the picture yet; and it seems Sebald’s cult status is still growing. There is plenty more to be said about all three and their associated colleagues and associates and I hope to be able to read it once I have reread these two volumes.

Rupert Loydell

(* One of the other film-makers mentioned is William Raban particularly his ‘Thames Film’. On the strength of this mention I bought a secondhand BFI DVD of Raban’s selected films, and can recommend ‘Thames Film’ as a dark, moody trip on the river from the city to estuary, with a focus on the industrial and decaying. Marvellous stuff!)