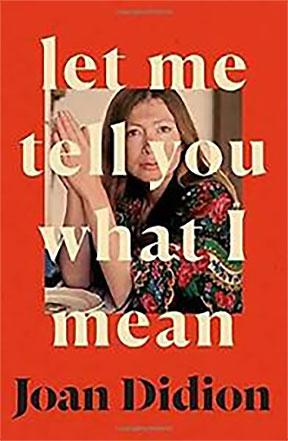

Let Me Tell You What I Mean, Joan Didion (hbck, £12.99, 4th Estate)

I’ve always loved Joan Didion’s work. Although in some ways part of the new journalism that emerged in the 1960s and 70s, where writers weren’t afraid to be part of their own story, Didion was always clearer, calmer, more lucid and detached than the likes of Tom Wolfe and his drug-fuelled hysteria. Didion’s non-fiction was spare and informed, but clearly rooted in her experience and opinion; her fiction was sparse and minimal, worked to the bone – and all the better for it.

Following her observations about the failings of the American counterculture and the rise of the right, she went on to document American intervention in Salvador, the fallout of 9/11 and the nature of grief and mourning following the deaths of both her husband and daughter. These felt like an ending, so it was a surprise when news of Let Me Tell You What I mean, a collection of twelve previously uncollected, pieces was announced.

To be honest the book is a bit of a let down, and feels like a scraping of the barrel. There’s nothing here to rival anything in Slouching Towards Bethlehem (1968) or The White Album (1979), let alone the complex emotional deconstruction of The Year of Magical Thinking (2005) and Blue Nights (2011). Some pieces are squibs – a slight reflection on not getting into her college of choice, for example, or the strange portrait of Nancy Reagan which is very much of its time and very ordinary; others about her own writing are more seriously disingenuous. If Didion really thinks she is ‘no academic’ and has no ability to think in the abstract, that she is unable to concentrate on anything for very long, or that she can somehow simply chisel away at words until they work, I’d be surprised. She is either playing the fool or the romantic, and neither do her any favours. (Let’s be kind and note these pieces are several decades old, but also note that she has allowed their republication.)

The first essay, about the ‘free press’ in contrast to the mainstream press, is engaging and witty enough, if a little obvious and dated. (Hilton Als’ foreword partly covers similar ground but more succinctly.) Elsewhere it’s disappointing to find Didion in the Ernest Hemingway fan club (what is it about his overwrought macho prose that so many people like?} or pages and pages about Martha Stewart, whoever she is. (The article suggests some kind of home goddess guru figure, who has made a financial killing out of domestic advice about interiors, cleaning and cooking. Thankfully she didn’t appear to make it over the Atlantic to the UK.)

Whatever Didion says, things do not simply talk to each other on the page, the author puts them in some kind of relationship with each other and the reader using written language. Didion may think this happens by itself, but that is to deny the thinking, planning, writing and editing that goes into all writing, and to abdicate responsibility. Whilst there are moments of sparkle and wit here, they are well hidden within this unfortunate gathering of minor pieces that, to be honest, would mostly have been better left uncollected and abandoned to posterity.

Rupert Loydell