Jeff Nuttall’s professional life started and ended in relative normality, first as schoolteacher and latterly mainstream film and television actor, but the dynamic central thrust of his work as writer, performer and innovator strained the belts of convention, as tightly as his notable girth. This new release by the VP Reprint Series of a quintet of seminal works by Nuttall, written between 1975 and 1994, shows not only how expert their author was as a stylist and storyteller but also how important he was as a thinker and spokesman for writing with a capital W, art with a capital A, and response with a suitably big R. He raged WAR on convention, first directly and then I am sure, in repose.

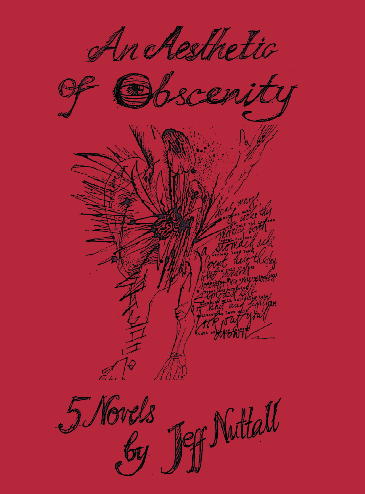

In editors Douglas Field and Jeff Jay Jones’ introduction, Nuttall is reported as formerly telling IT, that ‘I paint poems, sing sculptures and draw novels’ and so he does here, blending the forms in these effortlessly successful experiments and playgrounds for prose. The creamy heft of the paperback brings something of Nuttall’s silky corpulence to the hand and one is reminded instantly of his presence and voice on reading. The Gold Hole and Snipe’s Spinster are perhaps the most well known of the five books collected here but each is vital. For instance, the much neglected and shortest book, Teeth, written in a day after a booze infused challenge at The Groucho Club, shows how the most shallow of prompts can allow for the most profound and entertaining of speeches; Chapter Sixteen’s

‘Day spread itself apologetically, the way they sometimes do.’

echoes the opening lines of Beckett’s Murphy beautifully.

As the writer of one of the most famous books on sixties’ counter culture, Bomb Culture, Nuttall knew what to exploit and how to seek and advance renewal. His easeful control of all areas of literary, artistic and musical innovation were in many ways more impressive than his contemporary BS Johnson’s insistence on his somewhat stringent ideas for reforms to the style and content of the modern (or postmodern) novel. This is evidenced in specific details, such as references to the Edinburgh haircut received, marked and celebrated in the opening pages of Snipe’s Spinster. The prose sings due to its careful power and clarity and transmutes images upwards to the air, with the grace of cigar smoke, curling and coiling fresh thought. Written in first person, Snipe himself is a thinly disguised Nuttall who leads us through the remains of the society he signposted in Bomb Culture towards an acid tinged dawn. Pot (no pun intended) shots at various figures occur, most notably old IT associate, Mick Farren, but there is in the spite and subsequent drug struck languor, both an invective and charge at and for the pivotal forces of change. Sublime sentences drift past;

‘The acid wore off around half past eight and I went home, clip-clop down the mountain…lights of Leith winking like dropped glass..’

Or

‘..the rich, bright light that had shot across the city into my time-warps, swam in browns:’

Snipe, after his embibements of Guinness, light suppers of Ryvita and Cheese, experiments in homosexuality and desk tested erections thanks to female student Janet, resulting in ejaculations

‘that feel like a ‘bullet being drawn from a wound..delicately, carefully and with endless subsequent happiness’

meets up with associate and road manager Crane who after briefly swapping conspiracy stories tries to inveigle Snipe into the kidnapping of a Government minister’s daughter. The ensuing romp is ripe with the fruits of invention as Snipe’s Spinster, an aspect of the first person narrator’s own personality is endlessly subdued and challenged in 83 of modern literature’s most entertaining and subversive pages.

The House Party is even more revolutionary. It does what the aforementioned BS Johnson attempted with more brio than even he achieved in the Shandy-esque Travelling People, as form and layout, footnote, marginalia and illustration are blended into the thrust of the text to truly create the idea of novel as sculpture, as work of art in and of itself. This, then, is writing as its own lysergic. Rather than something that has resulted from the indulgence of substance, this is the substance itself. As Nuttall says in his introduction to the text, the book exists as an attempt to extend the possibilities of the blown mind and to see what that can really achieve. Full realisation at any cost. The House Party as a force for change and experiment, attempts to build on Joyce’s intentions in Finnegan’s wake which as quoted in the introduction was written ‘about dream, in the language of dream and about a dreaming man.’ and succeeds admirably. A parody of the country house novel it speaks through the experience of its four main characters and the sheer exuberance of its prose to the voice in the head of each reader that none of us can quite discern but which we each perhaps suspect is not entirely our own;

‘I could nudge you their nature, the lilyblow daffodils set in reverse, the childslace cupcakes turned in their cream, the swell and the suck-swell.’

‘Lay in the wet, in the swim, in the fishes and kippers that float up her fuck-tunnel,’ said George.

The mind shouts and flings its dream-paint over the drab confines of the skull, re-ordering it in an instant and teaching us that behind words and language itself is the vibrant desire to express every facet of existence and experience. All of Nuttall’s writing in this edition and what I know of his work through the beginnings of The People Show and the Performance Art Scripts are excavations of language and its possibilities. Indeed, they become challenges to the accepted and acceptable modes of expression that are often clogged or truncated by the pedestrian demands of common discourse. If you don’t have an appetitie for Hippo pudding by page 100, than sir, madam, you have no soul to speak of. And that is no something you will find in Robert Harris, or young master Amis.

As Field and Jones relay in their introduction The Gold Hole explores the ‘psychosexual landscapes of a methedrine fuelled poet, Sam’ and his declining relationship with former paramour, Jaz, set against the backdrop of the Moors Murders. In one chapter the aborted foetus of their lovechild speaks in eerie counterpoint to the novel’s setting, an innovation that certainly puts Ian McEwan’s latest novel Nutshell, to shame with its cursory retelling of Hamlet. Here is real tragedy writ large, and with a stunning level of precision and skill:

’During the first weeks I suppose you could have described me as an impulse of air. I was a small crisis of energy…’

‘At eight weeks I had something of the fish, something of the plant and something of the human…’

‘Sometimes the voice was like cocoa. I was often brown..’

The revelations drift past like shudders in the amniotic fluid, making us all mothers to our deeper and perhaps deepest levels of response. What strikes you by reaching the third book collected here is just how rich and strange Nuttall’s work and that of his contemporaries was and continues to be, whether living or dead. Modernist and the finest examples of post modernist thought and practise from Johnson to Paul Ableman, Laura Mulvey, Jane Arden and Helene Cixous and all points inbetween, exists beyond the constraints of their original forms and approaches. There is no dichotomy when I state that this child of Nuttall’s labours literally infuses death with a new form of life. Writing must transcend the page while still being of it and while contemporary performance, conceptualism and music often achieves this in isolated or singular examples, it is in someone like Jeff Nuttall that we see a sustained search for renewal of thought and response in every means possible.

Obscenity, if handled correctly as it is here on many of this volume’s seductive pages, is a weapon that flies with the grace of a bird. All of Nuttall’s writing chimes and resounds with that grace as he aims his flight in our direction. He wants us to celebrate and elevate the only true things we can draw on, where a ‘hand at the heaving ocean’ can bid the deep oyster to suck. The body’s lowest forms of function are consummations of experience in Nuttall’s worldview and sperm is mere paint in his hands. Piss revives as blood fuels. Shit affirms an intention. A kiss leads to clashes. A fuck makes the soul levitate.

In The Patriarchs, Nuttall explores his own writerly predicament as one of the successors to the previous literary generation though a canny exploration of the poet Jack Roberts, a figure bearing an uncanny resemblance to Ted Hughes. A symposium at a location that strongly sisters the Arvon foundation allows for responses to ebb and flow between writer and reader as the celebrity of the word is expunged. The limits and reaches of poetry and poetic definition are explored and commented on by Nuttall as unammed narrator, again by placing himself at the centre of the text. This once again fuses the forms as the density of the poetry on offer swirls around us;

‘Dancelocks lopped to the stubble by slums, /She scrabbles in refuse, can’t kiss or sing/ But thrashes on mattresses straddled by starvelings,’

and makes the novelist a conductor for and of the storm and to extend the metaphor, orchestra of response and intention. Nuttall as narrator comes not to praise or to bury Jack Roberts’ Caeser, but rather to examine his laurel wreath, the golden crown of achievement afforded to him and all of the other great voices of linguistic pursuit;

Beneath your voice, sticky flies play, choral over the filth of your dominion.

This truly is writing as Art. An aesthetic on beauty as well as obscenity in which the sound cloud (meant in the poetic sense and nothing to do with the interweb) created by words and their inherent meanings and intentions teleports the reader into higher levels of consciousness. One is struck by how useful the book is and how appealing because of the extent to which it provokes and elevates both engagement and response in the reader. You, we, I become active participants not just in and because of content as it is relates to us, but to the act of what encountering text is and can be, along with the potential of transcendence.

This collection is a riot of words formed by the decimations of convention won and raged by writers like Nuttall, BS Johnson, Sinclair Beiles, Heathcote Williams, Samuel Beckett, William Burroughs et al in the long decades before. It is both sharply observed and as adventurously surrealist as David Gascoyne in his prime or as coruscating as the poetry and poetics of George Barker, WS Graham, or latterly Iain Sinclair, Alan Moore or Brian Catling. Nuttall’s own court of miracles – to quote Catling’s recent poetry collection – is also one informed by the virtues of the entertainer he indubitably was. His work in the 1970’s with The People Show and other theatrical endeavours such as A Nice Quiet Night and The Railings in the Park, can still be glimpsed in the pleasantly familiar realism of Teeth, whose study of marital infidelity finds greater relevance through the feral fury of its female protagonists.

Jeff Nuttall was a teacher right to the end of his life, instructing us all on the potentials of our own efforts and showing how one could still throw the same sort of signal flares that Be-bop Jazz once fashioned, and that the theatrical Avant Garde developed across the other artistic forms in which it found fruition. He shimmered and glowed through all of his pursuits, cometing in from the basement of Better Books in 1967, to the old Traverse Theatre, Edinburgh in 1971, all the way through to Greenaway’s Prospero’s Books and bizarrely, ITV’s Kavanagh QC in the nineties. He was a star who shaped the sky to his own image and who allowed the song of art to attain the highest scale. This new reprint by the Verbivoracious Press re-introduces a master to his hopefully willing pupils and quickly and effectively re-orders the house of study into a new and thrilling combination. It is no stretch to say that the works collected in this volume are what Sterne would have grown into if he had an inch of Methusaleh’s reach.

The furthest branches of the tree are where the bird is now singing of forgotten stories and books strong enough to resist the fires of enveloping time. Amongst and above those spires of nature I am certain that the spirit of Jeff Nuttall capers nimbly beside the divine Ken Campbell and a chorus of other great ghosts and voices, from Chaucer to Charlie Parker, that are still responsible for our acceptance and understanding of what an idea is and can be. Nuttall’s house party is large enough to contain all of our efforts and the lives that surround them. As stated in marginalia on page 163:

‘Hack at the curtains. Hurl the stair rods at the windows in the front door. Slash the silken ankles’

And walk,

and as you do so, sing with this book as your guide.

David Erdos 9/10/16