“We put this festival on, you bastards, with a lot of love! We worked for one year for you pigs! And you wanna break our walls down and you wanna destroy it? Well you go to hell!“

By the time compere Rikki Farr took to the stage before a leviathan crowd of 600,000 to deliver his now infamous diatribe, the atmosphere at the Isle of Wight festival was curdling. Where the already much mythicised Woodstock festival the previous year had largely lived up to its’ promise of three days of peace and music, here was an even more densely populated powder keg of increasingly frustrated hippies enflamed by a contingent of agitators putting a loud voice to their discontent over the £3 admission price. The perimeter fence was the scene of pitched battles between advocates of the free festival model and security personnel, besieged day and night by French Maoists, Hell’s Angels and White Panther anarchists chanting “music should be free.” Thousands evaded payment by camping on a neighbouring ridge with a perfect view of the site, soon dubbed ‘Desolation Hill’ by “people who came not to dote on superstars, but on each other” in the words of Richard Nevile. On more than one occasion radicals had leapt onto the stage to deliver rants about what they perceived to be the commercial exploitation of the counterculture, interrupting performances by Joni Mitchell, Sly & the Family Stone and the Pentangle. Later, an uncharacteristically lacklustre set from seemingly acid-addled headliner Jimi Hendrix was followed by DJ Jeff Dexter returning flustered to the fore. “We seem to have a fire, could someone help us?” he appealed.

That the third Isle of Wight festival had descended into farcical bathos wasn’t the first symptom of a decelerating zeitgeist- and it would be far from the last. Within weeks, Hendrix was dead, and Janis Joplin wouldn’t be long behind him in joining the swelling ranks of the notorious ’27 Club.’ Some months prior the Beatles had gone their separate ways, opening up a power vacuum on the upper rungs of the charts. It was 1970 and the Psychedelic Sixties were dead, seemingly dragging their unrepeatable brew of benign idealism to the grave with them.

It’s not difficult to discern why the dawn of the new decade is often related in terms more befitting the end of an era rather than the beginning of a new one, characterised in hindsight as a something of an anticlimactically drab cultural no-man’s land. Stranded adrift between the experimentalism of the psychedelic boom and the garish rise of glam, 1970 saw the musical stylings of the previous years splinter, coalesce and evolve as though striving to recapture the magic of the late sixties through trial and error. Nonetheless, despite the seemingly bleak musical forecast, Derek Taylor’s final Beatles press release is inflected with cautious optimism for the brave new post-Fab Four world. “The world Is still spinning and so are we and so are you. When the spinning stops, that’ll be the time to worry. Not before. Until then… the beat goes on, the beat goes on…”

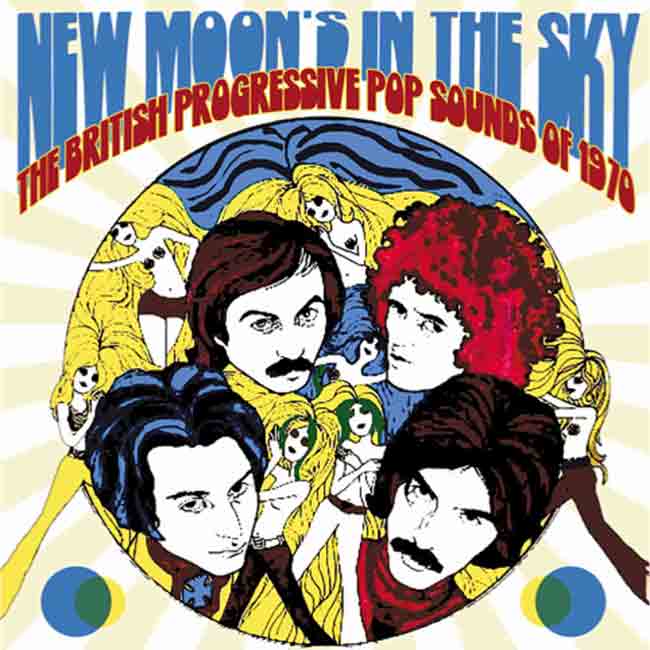

Enter Grapefruit Records and their newly released 3CD retrospective, ‘New Moon’s In The Sky: The British Progressive Pop Sounds of 1970’, which goes some way to redefine the oft-misunderstood landscape of the British music scene at the turn of the decade.

The latest in Grapefruit’s run of chronological releases focusing on British psychedelia, (which began in 2016 with the 1967-focused ‘Let’s Go Down and Blow Our Minds’) ‘New Moon’s In The Sky’ carries a slightly different subtitle from its’ predecessors. As compiler David Wells writes in the extensively researched accompanying 52-page booklet, “where does a compilation series that’s been devoted to British psychedelia during the relentlessly- Swinging Sixties go when we reach the Shagged-Out Seventies?” It’s a valid query; if psychedelia was considered yesterday’s trend in 1969, the label may as well have been ancient history come 1970. However, In the wake of the runaway album chart success of prog-oriented ensembles like Pink Floyd, King Crimson and the Nice, progressive rock was very much in favour with the underground. As had transpired with the commodification of psychedelia in the mid-sixties, the sound of such so-called progressive music percolated out from clubs like Mothers and the Marquee and through to more commercial groups in dire need of a new fad to follow. Accordingly, ‘New Moon’s In The Sky’ deals with the peculiar subgenre of progressive pop, gleaming its’ exhaustive tracklist from the more accessible, song-oriented recordings of the period.

It makes for eclectic listening, to say the least. ‘New Moon’s In The Sky’ trawls deep through the archives, with the usual Grapefruit fixation on the esoteric (Needless to say, Savwinkle & Turnerhopper, Bachdenkel and Doctor Father are far from household names) and the underrated- Meic Stevens’ wah-wah laced ‘Rowena’, for instance, makes a strong argument in polar opposite to the contemporary Melody Maker review that surmised there was “little originality about his songwriting at all”. Over the course of the three discs that compose the set, the teenaged Stray sing a song inspired by the works of Jules Verne; there’s the groovy theme music for turn-of-the-decade children’s programme ‘Ace of Wands’ courtesy of Andrew Bown, and Canticle perform the Small Faces’ ‘My Mind’s Eye’ as an unlikely good-time folk rock fiddle romp far removed from its’ sharp-suited mod beginnings. Oh, and the whole thing closes with Bill Oddie doing a Joe Cocker impression.

The collection leads off fittingly with Procol Harum, who arguably invented progressive pop with 1967’s runaway smash hit ‘A Whiter Shade of Pale.’ Recorded under the working title of ‘Wash Yourself’, ‘Piggy Pig Pig’ is described aptly by compiler David Wells as “an updating of ‘I Am The Walrus’ for the new decade.” Unremitting in apocalyptic surrealism (“streets awash with blood and pus” stands out in particular amidst the marching gloom), the song not only provides the origin for this compilation’s name but also captures lyricist Keith Reid in what he belatedly identifies as “a deeply depressed state”. With two tracks on ‘New Moon’s In The Sky’ sharing the grim title of ‘Time to Die’– the first a soulfully bluesy, unplugged exercise courtesy of Patto and the second an evocative, acoustic-led period piece by Ancient Grease- it’d be easy to assume the primary theme of this collection to be one of pessimistic acceptance. Quite the opposite is true- if anything, one of the major undercurrents here is reinvention, with varying levels of success. Such pragmatic opportunism, this compilation shows, could often yield results of surprisingly high quality. For instance, former Crocheted Donut Ring vocalist Richard Mills, together with River bandmates Alan Gray and Chas Mumford, may never have cut their at-the-time-unissued, go-go riffed cover of Shocking Blue’s ‘California Here I Come’ had the latter not had a hit with ‘Venus’. If it had been released, it could well have landed River a hit single.

The Tremeloes, who are represented here with their Beatles-influenced Top 10 hit, ‘Me and My Life’, made a less accomplished leap into the great unknown of the new decade. Known in the Sixties for such lightweight pop fare as ‘Here Comes My Baby’ and ‘Silence is Golden’, 1970 saw them announce they were “going heavy” in an interview to promote their upcoming album, ‘Master’. In a marketing move so comically misjudged it wouldn’t appear out of place in ‘Spinal Tap’, the band alienated their own fanbase by claiming only “morons” could have bought their earlier singles. Whether or not this assessment is true is beside the point- the Tremeloes would never again score another UK Top 30 hit. The Move adjusted somewhat better to the Seventies biosphere, rescuing themselves from the “lucrative but soul-destroying cabaret circuit” with the stomping ‘Brontosaurus.’ Subsequently released as a B-side, ‘What?’ is included in this set and pre-empts the heavily produced, symphonic sound of Electric Light Orchestra. Adaptation not only in sound but in name was also a means of protecting the delicate public of 1970 from obscenity- as was the case with a band from Basildon called Bum who were encouraged to rename themselves the Iron Maiden. No, not the Iron Maiden you’re thinking of.

Other groups were apparently determined to shed the baggage of the Sixties and begin entirely anew- indeed, psychedelic connoisseurs may discover that the seemingly impenetrably obscure roster of names featured in this compilation features plenty of cult favourite artists recording under new monikers. The Flying Machine are in fact an evolved incarnation of one-hit wonders Pinkerton’s Assorted Colours. The Mirage? They aren’t here, but try Portobello Explosion- oh, wait, their cover of ‘Across the Universe’ is included under the new denomination of Jawbone. The lilting acid folk treatment of the Alan Hull composition ‘United States of Mind’ on Disc Three is attributed to Affinity, in reality former Decca psych pop act Ice augmented with newly recruited vocalist Linda Hoyle. The Fut? Don’t you mean the Beatles?… alright, maybe not. Although ‘Have You Heard The Word’ sounds so much like a 1967-era Beatles recording that Yoko Ono tried to copyright it in 1985, the Fut were actually Australian duo Tin Tin reinforced with Bee Gee Maurice Gibb (who managed the spot-on John Lennon impression despite having broken his arm earlier in the day and “suffering from a potent combination of painkillers and alcohol”). Regardless, it featured on several Beatles bootlegs, with some even attempting to pass it off as the yet-unreleased fruits of the ‘Carnival of Light’ session.

The dearly departed Beatles hang like a spectre over much of ‘New Moon’s In The Sky’- Penny Arcade transform ‘Let It Be’ opener ‘Two of Us’ into a breezy slice of baroque pop, and Gerry Rafferty of the Humblebums manages to channel both Lennon and McCartney simultaneously on the melodic ‘All The Best People Do It.’ Octopus persevered with their Beatlesque style until 1971, with the urgent ‘Thief’ compiled here sounding like a psychedelicised ‘Rubber Soul’ track, whilst Fickle Pickle wear their influence proudly on their sleeve through the rich harmonies of the heavily orchestrated ‘Sam and Sadie.’ Several acts contribute excellent music that is nonetheless at odds with the supposedly progressive trends of 1970; Rusty Harness’ ‘Goodbye’ sounds like a relic of the mid-Sixties U.S garage boom, and the woozy popsike of Airbus’ ‘Alias Oliver Dream’ (not to mention Blonde on Blonde’s beatific ‘Castles in the Sky’ and the twee bubblegum of Angel Pavement’s ‘Jennifer’) would sound much more at home nestled alongside similarly florid releases dating from the Summer of Love. Such recordings sound bizarrely anomalous alongside the likes of Hawkwind, U.F.O and Steamhammer (with whom they share disc space) but therein lies their charm.

For every ending ‘New Moon’s In The Sky’ documents- the final recordings by Plastic Penny and Andromeda are featured- there’s plenty to indicate the shape of things yet to come. Not long after recording ‘He’s Growing’ for the Gods’ underrated second album ‘To Samuel A Son’, multi-instrumentalist Ken Hensley and drummer Lee Kerslake would begin their tenures in Uriah Heep. Yellow Taxi’s slightlydelic proto-glam ‘Anna Laura Lee’ pre-empts the hitmaking formula the Sweet (who appear on the first disc) would soon follow. She Trinity’s bombastically wigged out ‘Climb That Tree’ sounds akin to a bizarre synthesis of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s ‘Jesus Christ Superstar’ and the ‘Wicker Man’ soundtrack. Curved Air are captured on the cusp of their singles chart success (‘Backstreet Luv’ was only a few months removed from ‘Blind Man’, the album track spotlighted here), as are Atomic Rooster, with the inclusion of a demo of their anthemic future top 5 hit ‘Devil’s Answer.’ Hopefully a 1971 themed retrospective will see the light of day next year so these developments can be traced even further.

Often enlightening, consistently enjoyable and occasionally uneven, ‘New Moon’s In The Sky’ is a worthy addition to the Grapefruit discography, and yet more essential listening for those who know their Kevin Ayers from their Paper Bubble. Each release from Grapefruit is a labour of love, and it shows- from the extensively researched annotations within the lavish booklet, the immersive period artwork adorning each discs’ paper sleeve, and the continued commitment to rescuing unreleased recordings from the purgatory of the cutting room floor. Here is a fresh, in-depth overview of a year of sweeping transition in the British music world- and one that proves, to quote compiler David Wells once more, that “maybe 1970 shaped up pretty well after all….”

-Jack Hopkin, 2019