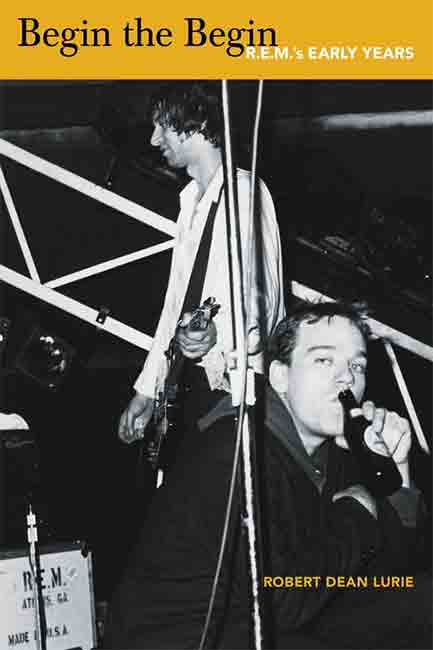

I do not often read books about music and musicians, but something about Robert Dean Lurie’s ‘Begin The Begin: The story of R.E.M.’s early years’ caught my interest. Certainly of the music I listened to during the period from, say, 1983 to 1985, those first three r.e.m. albums are the records that I would say still hold some kind of strange beguilement; are the ones that conjure strong personal memories and yet simultaneously manage to slip through the grasp of understanding and remain both elusive and illusive. Perhaps only the contemporaneous albums by The Go-Betweens are a match in this regard, personally speaking. In his book Lurie certainly does a good job of drawing together the threads of narrative that combined to mould the group and in so doing widely acknowledges the broader context of Athens and its artistic mythology. At the very least it had me scurrying back to play those old Pylon records, which still sound magnificent, and of course tangentially out to the Let’s Active records too and that is always a treat. It’s ‘Fables of the Reconstruction’, ‘Reckoning’ and ‘Murmur’ though that remain the ones that soothe and confuse in equal measure, and it’s to Lurie’s credit that he has made me want to immerse myself once more in the pleasures and pains held within their grooves.

Naturally I understand why Lurie’s book also takes in the ‘Life’s Rich Pageant’ and ‘Document’ albums (they are the necessarily ‘bigger’ records that bridge to the ‘major label’ breakthrough to mainstream recognition), but I admit that whilst both those records hold some treasure (the gorgeous Pop tingle of ‘Fall On Me’ would be the prime example) they leave me mostly cold now. I’m sure I have said it before, but I am certain this is largely because on those records you can actually hear what Michael Stipe is singing about and, for the most part, stripped of the shivering uncertainty of meaning held in the previous records, it all feels somewhat flat and worthy. It’s probably why I found those later chapters in Lurie’s book to be increasingly less engaging, as r.e.m. grew into R.E.M. and, increasingly shorn of art-rock local folkloric roots, became more another example of rock orthodoxy.

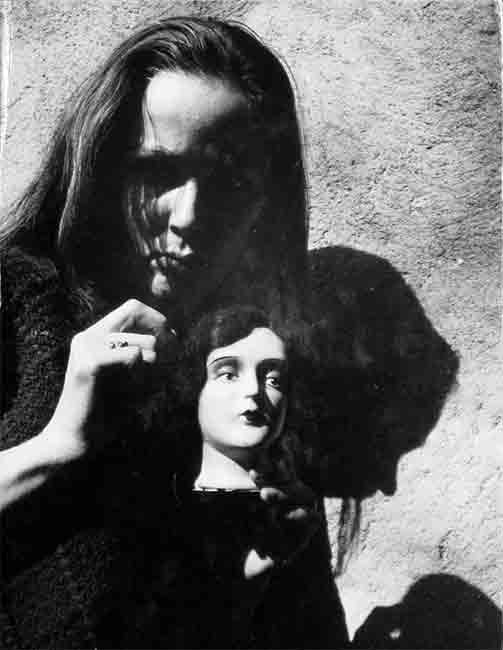

I should point out that I have no problem with R.E.M. and their subsequent global success, just that personally I have no interest in the records that followed. I’ve not got a huge amount of interest in the artistic life of Stipe post ‘Fables’ either, and I admit that what I have seen of his own photography work has left me balancing on a point between vaguely interested and distinctly underwhelmed. Certainly I have found them less interesting than, say, Dennis Hopper’s (to pick another artist from another medium whose photography might otherwise never have seen the light of day if not for their ‘celebrity’). Much of the interest in Hopper’s photographs now is as documentary evidence of history and culture (his shots of Hell’s Angels and of Sunset Boulevard riots in 1967 are particularly fascinating) but there are certainly threads of creative exploration evident throughout those images collected in ‘The Lost Album’ that bear out what Hopper said about the camera being, in the years between 1961 and 1967, the only creative outlet he had and that making those photographs “kept [him] alive”. There is certainly something of the obsessive amateur in the work, and as a tangential jumping off point I admit I keep getting drawn back to a particular 1962 shot of Brooke Hayward with a doll’s head.

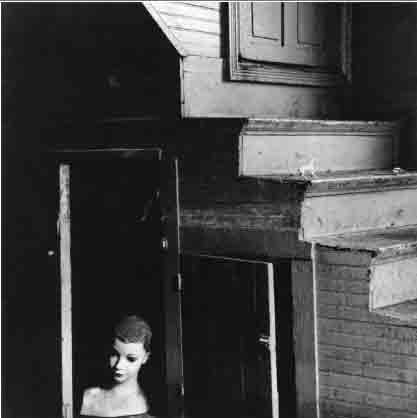

This shot of Hayward and the doll’s head is a tangential point of reference because it reminds me of the celebrated work of another ‘amateur’ photographer, Ralph Eugene Meatyard. And whilst I say celebrated of course I admit that I have personally only stumbled (if you will excuse the pun) on Meatyard’s work thanks to Lurie’s compelling theory about the origins of the r.e.m. band name. In brief the theory goes thus: Michael Stipe, as an art student with an interest in photography and folkloric/outsider art, would undoubtably have come across the work of Meatyard in his studies/explorations (there are strong connections between the aesthetic of Meatyard’s work and, say, Howard Finster’s Paradise Garden or R.A. Miller’s garden of whirligigs that feature in the early R.E.M. promotional videos); Meatyard signed his correspondence with his initials, in lower case (r.e.m.); in their early years the group’s name on flyers, posters etc was similarly often written in lower case… So is the connection between Meatyard and the origins of the r.e.m. band name real/true? In hindsight it feels like a pleasant detour in meaning if nothing else, yet also entirely in keeping with a group who, in those early years certainly, seemed keen to keep the mysteries caged.

Meatyard too kept the mystery caged, being famously mute when sharing his work with fellow members of the Lexington Camera Club and rarely if ever giving interviews or talking about his photographs. What he did say about his work however is intriguing, particularly in reference to any connection into the music of early r.e.m. Certainly the notion of his work as being “romantic-surrealist” dovetails neatly with many of the songs from those first three r.e.m. albums which are so often suffused with a haunting Otherness with Stipe’s lyrics out of focus and lacking much meaning beyond abstracted associations of sound. Meatyard said about his famous images of his family members dressed in Halloween masks that the masks and the doll’s heads were there to function as ways into the photographs but that the more lasting interest would be in the backgrounds. Certainly they are photographs that reward repeated viewing. Those first three r.e.m. albums work in a not dissimilar way, where melodies and the occasional clarity of a lyric pulls you into a song that rewards with textures and shifts of light and dark that reward repeated listening.

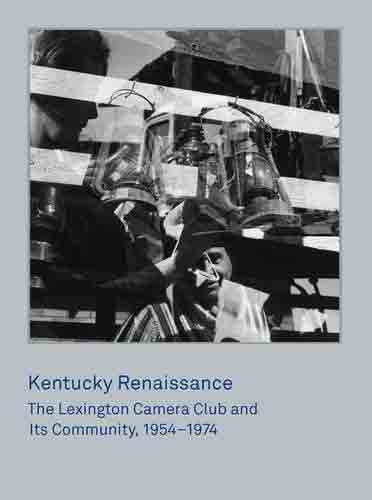

In his essay that opens the ‘Kentucky Renaissance’ book about the Lexington Camera Club, John Jeremiah Sullivan writes that “[In the South], perhaps, we imbue our artists with a unique luminosity. We need them. And when a community does manage to form, however loosely, there’s a glow. You’re huddling together inside something, inside a culture, but against something too.” and it strikes me that this could just as easily have been Lurie writing about the Athens musical community in the late 70s and early 80s. Indeed, it is the threads and connections Lurie traces between people from that period that are the most intriguing and engaging elements of ‘Begin The Begin’ and I admit that reading the book had me digging out that ‘Athens Inside/Out’ DVD again. And just as Lurie has me scurrying back to listen again to groups like Love Tractor, Flat Duo Jets and (especially) Pylon, so ‘Kentucky Renaissance’ has me eagerly seeking out Charles Traub’s ‘Edge to Edge’ landscape photographs and Cranston Ritchie’s wonderful experimental work involving panning and tracking. Then too there is the work of Robert C. May and particularly his shots of Ralph Eugene Meatyard’s son Chris (sans Halloween mask) from the early 70s which could easily be taken as blueprints for the Michael Stipe aesthetic from a decade later. Indeed, the shot of Chris Meatyard reclining on an old mattress illuminated from behind by a window apparently shorn of glazing but with a wrapped fragment of sheer curtain tied in its lower frame, might be of Stipe in the old church on Oconee St in Athens and maybe, if the shot was in colour, the light might be green just as it is in what is perhaps my favourite of all R.E.M. songs, the gorgeous ‘Camera’.

Not ever having been what one might call an obsessive about the group it was only on reading Lurie’s book that I came aware that ‘Camera’ is ‘about’ fellow Athens community member Carol Levy, a photographer who shot the band for the rear sleeve of their Hib-Tone debut single and who tragically died in a traffic collision just a day after the US release of the ‘Murmur’ album. Lurie suggests that “Carol Levy’s spirit hangs palpably over the origins of the Athens music scene virtually everywhere you turn”. It is tempting to suggest such a reading is informed at least in part by a knowledge of the tragic circumstances of her death (it is always easier to read significance into the lives of those who leave us young than in those who lead longer lives and -perhaps- fade from narratives) but then again, there is a photo much earlier in the book that shows Lynda and Cyndy Stipe dancing in a club whilst behind them, only just visible, is Carol Levy. There is an immediately energising vitality about this fragment of image that is inescapable, so perhaps there is something in what Lurie says after all. Certainly there is a significant sense of loss, love and presence in ‘Camera’ and it is to R.E.M.’s credit that it is a presence you sense without any knowledge of the song’s origins or meaning. Stipe has said that this pretty much ended his period of ‘autobiographical’ song writing, though the threads of personal meaning are always obtuse and broadly suggestive rather than explicit. To draw another parallel into the world of the Lexington Camera club, where Charles Traub talks about how “photography is about seeing what the world looks like as a picture” then perhaps these early r.e.m. recordings are about seeing what the world looks like as a song. Indeed, in her essay that accompanies the Radius Books publication of Meatyard’s ‘Dolls and Masks’ photographs, Eugenia Parry writes that “the photographs of Ralph Eugene Meatyard are mystery plays”. One need only change “photographs” to “songs” and insert Meatyard’s initials to see the sentence as an accurate description of ‘Murmur’, ‘Reckoning’ or ‘Fables’.

Maybe there is something in Lurie’s theory after all.

Alistair Fitchett 2019

‘Begin The Begin. R.E.M.’s Early Years’ by Robert Dean Lurie is published by Verse Chorus Press

‘Kentucky Renaissance. The Lexington Camera Club and Its Community 1954-1974’ is published by Yale University Press in association with the Cincinnati Art Museum

‘Ralph Eugene Meatyard: Dolls and Masks’ is published by Radius Books

‘Dennis Hopper: The Lost Album’ is published by Prestel books