War is very much on our minds at present, with the publication of the Senate report into the state sponsored torture of suspects at Guantanamo, the shocking fact has emerged that this was happening in a ‘civilized’ democracy. You begin to wonder what else is going to emerge – particularly in view of the fact that there are major elections coming up in both the US and UK? Plenty I’m sure. The most shocking revelation of all, though also it is the most obvious, is the undeniable fact, confirmed by ISIL late last week, was that the Islamic State was created at Guantanamo Bay.

And so it is that the UK and USA have lost the moral high ground as a result. It reminds us of the dark days of the Cold War and the state sponsored use of torture by the Communists. We seem to have forgotten that the Iron Curtain fell; the torture of suspects having failed to produce any long-term effect other than to point out quite how redundant the use of torture truly is. The irony of this is that it is a subject heavily defended by the religious right. Perhaps this is a kind of historical Stockholm Syndrome: a reminder of the martyrologies of the founding saints of the church. These martyrs eventually contributed to the fall of the old Roman ethic expressed in paganism and led to a more state-centred approach to religious mores wherein we had the emergence of the Roman world’s first example of a theocracy: the Christian example having been taken from the template of the Second Temple in Jerusalem. We seem to be heading down the same rocky road. As Santayana said: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it: first as comedy, then as tragedy.”

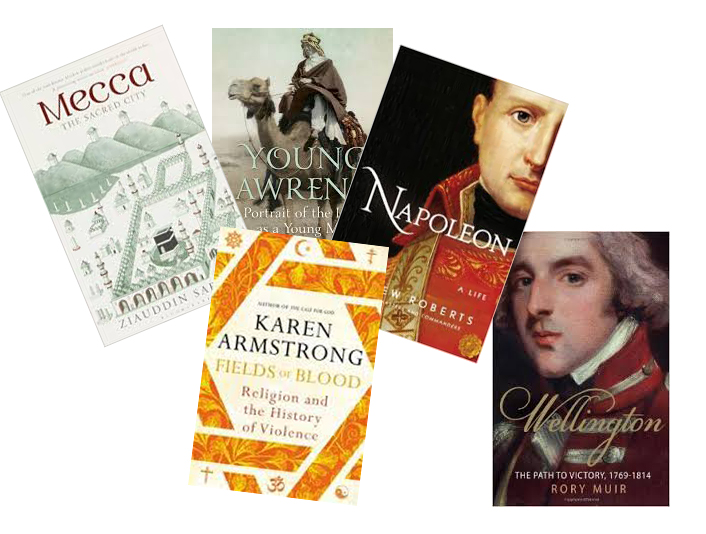

Rome, as an example of ‘civilization’, is a view currently under revision – the old chestnut of empire being the heart of the issue: Rome saw war as necessary to her political and expansionist aims: we have hardly ever been at peace since. Prof Bob Brier once made a very good observation when he stated that no other form of religion has caused as many wars as monotheism and this brings us the Karen Armstrong’s very absorbing text, Fields of Blood, Religion and the History of Violence, (Bodley Head, £25.00). Armstrong’s style of writing is simple but compelling and she presents her arguments with great clarity. Her theme is that of agrarian versus egalitarian societies in the rise of religious warfare.However, she is quick to observe that Religion is merely the excuse for war, not the true reason and in this she has a good point in that all wars are inevitably political, the Roman ethic is still very much in practice..

Recent academic studies have demonstrated that the practice of religious spirituality is rather effective in controlling some of the more violent urges of individual humanity; it can lead to greater inner peace and also has remarkable health benefits. So how do we square this with the idea that religion is anathema in a cultured society?

In the very ancient period religion was effectively the response of ancient societies to the uneven tides of nature, which were themselves the consequence of other phenomena. Egyptian civilization lasted so very long primarily because the Nile could be relied upon to flood on a particular date every year. The Nile was seen as divine in its constancy and thus a whole civilization could tell the time by it. Sadly this was not the case in other parts of the near east where it is easy to se that religion was based less upon constancy and more upon the individual travails of a humanity struggling to survive in harsher terrains as weather patterns changed dramatically. It is interesting how these early societies were very knowledgeable about astrology and astronomy. This was their one reliable method of seeing time, of judging the sowing of crops, but as Armstrong points out once the agrarian cycle of society passed into the idea of the city state wealth became the main cause of human tumult – religion became the path to settling these issues. We can see it today in the green issues surrounding present policy. On the one hand today’s politicos use the term production on such a regular basis that they have forgotten that it is production that has put us into the mess we are in – it has become a contradictory idea when used in tandem with Green ideas. Armstrong contends that religion developed as an approach to an intellectual understanding of where we are. Of the state we are in. Buddhism and Christianity are famous for opposing war and for promoting compassion and understanding of the poor. How ironic that Christian civilization has seen fit to conveniently ignore these basic needs: it is one of the less-spoken of Roman ideals that has survived: the pursuit of wealth through empire at the expense of much else. violence is seen by some as in the main ‘patriarchal’. The Mother Goddess offers more utopian view as it did in Celtic societies but at the same time where these societies were known to have been technological (much more so than the Romans) and advanced, but who never traded beyond their means thus avoiding the problem of increased production– their never was a Celtic idea of ‘empire’ which makes the recent idea of the ‘Celtic Tiger’ all the more tragic. The European Constitution is based on The Treaty of Rome.

The past always sticks.

The Excellent Mecca, The Sacred City, by Ziauddin Sardar (£25.00, Bloomsbury) is written with the kind of charm that hides menace in the telling. It is a travelogue through the history of the Holy City. Part paean, part critique, it meanders through the strange history of this extraordinary city, which still offers its compulsion to the weary pilgrim; but you get the sense that the book is an elegy to what must once have been a profoundly beautiful presence, beautiful in the sense of what it had to offer and how the offering was but a part of the revelation of the divine and the experience if it. The author ends his work with a very sharp critique of what the present ‘protectors’ of the city are doing to destroy it. Large parts of the Ottoman quarter no longer exist; bulldozed to make way for a more money centred idea and view of the vision of heaven. Wealth has played its part in this of course, and to such a degree that the response of some has been a terrible urge to violent outrage that has its expression in the wider world at large: seen in this way, as an anguished howl of rage we seen also the wider domain of the suppressed voice. This is a beautifully written book that does not shirk from telling its truth and offering us a vision of the future wherein the modern idea of ‘productivity’ comes in the form of the pilgrim, who is only viewed in a commercial sense – a modern tourist: spirituality has forgotten the difference. The mystique is now hidden, buried deep, as a naked singularity is clothed by detritus gathered around it, for where is history not defined by the people who inhabit it?

One such example is the enigmatic figure of TE Lawrence AKA Lawrence of Arabia, a trendily maligned, though much-misunderstood figure who was horribly let down at the end of the war by the perfidy of his imperial masters. In Young Lawrence, A Portrait of the Legend as a Young Man by Anthony Sattin (John Murray £25.00) we bear witness to the beginnings of betrayal. Books on Lawrence represent a veritable industry so to find a new angle is uncommon. Sattin is a travel writer as well as a biographer and he observes Lawrence from both of these angles with aplomb. Lawrence had a tortured relationship with his parents and his need for solitude was in large part a result of his over-bearing mother’s attempts to rule his life. (A testimony to this is the Christian inscription on his gravestone in Dorset, the last vestige of attempted motherly domination, a domination and influence Lawrence had rejected very early on). Early on in his academic career Lawrence set off on hair-raising trips to Europe and the Middle East, where he learned to speak Arabic and where also he was able to complete his astonishing thesis on Crusader Castles. There is much here that is new and in following Lawrence’s trail Sattin has offered up an insight into the later activities of Lawrence on behalf of the Arabs. Later on in his youth Lawrence was to be involved at the excavations in Carchemish under the aegis of Leonard Woolley. It was also at this time that he was recruited by the British as an intelligence officer, a role he used to extraordinary effect in the coming World War.

Imperialism is the key here, expansion led to profit using the narrow excuse of trade but denying that it was in effect protectionism. How it has pervaded our thinking since. Even science has to be ‘empirical’ if it is to have a place in our rather confused place at the crossroads of civilization. War was become the best way to polish this modus operandi. Next year sees the bicentenary of the Battle of Waterloo – a battle that saw the decline of one empire in favour of another, a war that had raged throughout Europe and beyond and is still the cause of considerable debate.

Wellington, The Path to Victory by Rory Muir (Yale, £30.00) is quite the best biography of Wellington that I have ever read. It is a surprisingly engaging read that is as compelling as it is informative. The old schoolboy image of Wellington as the stuffy aristocrat of legend, born to aloof splendour, in a world where prearranged payment saw one’s rise through the ranks regardless of ability, has now been laid to rest. The key to Wellington is discussed brilliantly in this epic work. This is the first of two volumes. Wellington’s future ability and his eye for logistics and the unerring ability to plan and organize has troops was profoundly affected by the British forays into the Low Countries in 1794-5, in the early part of his career. The campaign was a disaster from beginning to end and for Wellington it was the defining moment in what was soon to become a glittering career – but one borne of very hard work and equally hard experience. One gets early on the sense that his later aloofness was born of pain and compassion in equal measure. It was a means of coping. Wellington comes across as an entirely compassionate man more so than might have been deemed appropriate given the fashions of the day. This makes some of his later pronouncements all the more understandable. On the eve of Waterloo he was inspecting his troops incognito when he encountered a band of Irishmen, drinking heavily and giving free reign to their ferocity of intent in battle on the morrow. Wellington was heard to exclaim that he hoped that they would terrify the enemy because they certainly terrified the living daylights out of him. Like his bête noir, Napoleon, Wellington quickly saw the value of discipline in military campaigning. He was genuinely concerned for the welfare of those who served under him and, unlike Napoléon, did seek in small part to improve conditions, though he was much hampered by domestic politics and the need to answer to parliament for his actions in India during the years 1796 – 1805. But of course the making of Wellington’s reputation was the Spanish Peninsula campaign from 1809 to the eve of Waterloo. Muir describes this remarkable campaign with in good detail always with an eye towards to the development of Wellington as both officer and man. This volume is the War and Peace of its time, it is exciting and the battle sequences are written in such a way that the reader is compelled to read on – as I did into the early hours of the morning. I await the second volume with anticipation.

2015 is also the year of Napoleon. Too often the British see him as the loser of Waterloo rather than the great reformer of a Europe still emerging from the chaos of the anti-enlightenment backlash – a Europe that was ripe for change and which had the great fortune to see the rise of one of history’s greatest.

Not unjustly is he called Napoleon the Great by Andrew Roberts (Allen Lane, £30.00) in his new swashbuckling and somewhat witty biography of this titanic figure. Set against this we also have the first in a two-volume biography Napoleon by Michael Broers (£30.00 Faber). This latter is a steady and considered piece of writing that from the outset seeks to underline – and correct – some of the more mythological scenes scattered throughout Napoleon’s life: some of these fanciful conceits were uttered by the great man himself. Of his birth he said: ‘…I was born not on a bed but on a heap of tapestry’. It was said that the carpets depicted scenes from Homer’s Iliad. As Broers, Professor of Western European History at Oxford University points out in the opening pages of his impressive text, ‘No one had carpets in Ajaccio in 1769, certainly not the Buonaparte, and they were not for summer use in any case.’ As Broers points out, there is no need to mythologize Napoleon’s life and career; the truth is more than enough to cope with.

Roberts underlines this with a lot of copious detail and a lot of what might be considered superfluous fact, but in the end you realize that the sheer level of information, the kind that you might find in the more obscure quiz ages of historical journals, works its effect in bringing alive this important and, in Britain, much maligned figure. Broers and Roberts have trawled well over 30,000 letters and memoranda in the Paris Archives to search for the real figure, the every day, demythologized figure and yet, in conclusion Napoleon, because of the sheer scale of his achievement emerges from these pages as a kind of frenetic superman but brought low by the all too human. He never drank spirits (think ‘Napoleon Brandy) and yet took with him on campaign over 800,000 pints of red wine. He instituted a new system of uniform measure across the empire and homogenized the domestic civil service, abolished anti-semitism and the ‘Holy’ Inquisition. He introduced street lighting and instituted the Legion d’Honneur, improved education issued pensions to his soldiery and created what was in effect a meritocracy.

If Louis XIV could say; ‘L’etat ce mois’ Napoleon bettered it by going further: ‘I am the revolution’. This sounds all too bombastic in the modern European world but we must not forget that France was at this point in time yet to emerge from the Feudal privileges of the aristocracy and, as their heads began to roll, anarchy was given full reign. Napoleon saved France and brought Europe into the modern age – we have that to thank him for.

And yet, for all this Napoléon was a megalomaniac, A victor of so many battles – all of them chronicled and detailed by Roberts – whose tactical genius was brought low by the cold, good manners and egregious workmanship of an Anglo-Irish Duke. He was the enfant terrible of his time and, as Roberts points out, at the end he simply appeared to run out of steam his final fatal miscalculation occurring on the field of Waterloo. Quite simply his luck ran out – and into Wellington’s camp – had it not been for the late arrival of Blucher on the field Wellington would have been done for. As he aptly remarked in the immediate aftermath; ‘It was a damn close-run thing.’

David Elkington