The Aesthetic Transformation of Perception

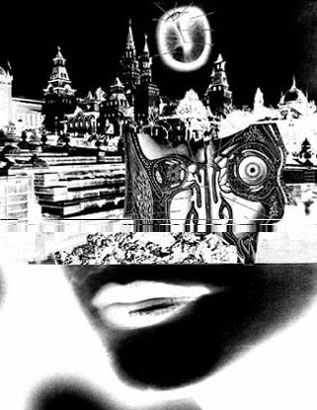

The aesthetic transformation of perception is closely linked to the purification and transmutation of language: the alchimie du verbe of which Rimbaud and the Surrealists spoke.

The transformation of perception arises from the disclosure of the Essential, the revelation of the Quintessence, and from the elimination of all inessentials, all deadly serious prosaic elements.

It is this ‘alchemical’ or Hermetic theory of poetic language and aesthetic image, to which Mallarme was alluding when he referred to the task of giving ‘a purer meaning to the words of the tribe’ and which lay behind Baju’s desire to re-designate the Decadents as the ‘Quintessents’. In this sense the poet can become a shamanistic custodian of the modern – or the traditions which comprise the modern, for traditions enshrine ways of seeing the world and, contrary to popular belief, are never static, mutating in response to deep-running, impersonal. evolutionary currents. In this sense the ‘visionary’ role of the poet, uniquely attuned to these mutations, is not metaphorical – he, or she, may become the instrument of change – change, through transformation of perception.

In his seminal Lettres du Voyant Rimbaud defined the visionary role of the poet of the future as ‘the supreme savant’, the initiator of universal transmutation, the harbinger of a new era in human evolution, un multiplicateur de progres.

The poet would define the amount of the unknown awakening in the universal soul in his own time. He would produce more than the formulation of his thought or the measurement of his march towards progress.

Poetry, like all art, should be founded on a special vision of the world, a different way of seeing. To a degree any artist will transgress accepted ideas of normality, if only by presenting familiar objects and situations in an unusual way. Poetry is bound to conflict with consensus opinion because the special vision will incorporate the negative as well as the positive. As Sartre once said ‘literature is, in essence, heresy’. When an artist – the poet, the novelist, the composer, the trapeze artist – adopts a different way of seeing the world he or she has taken the first step towards total idiosyncratic vision attained through various stages of initiation. This initiation will involve a state known as ‘the dark night of the soul’ in which enhanced awareness of ‘supernal’ perfection, the Ideal, or, to use Mallarme’s phrase, ‘the dream in its ideal nakedness’, leads to a similarly enhanced awareness of human imperfection. For Baudelaire awareness of human or worldly imperfection was called spleen, for the alchemists it was the Nigredo or ‘blackening’. Celine used the term noircissement to identify the same state of mind – a night-world of horror, viciousness, pain and dread. It is this ‘core of horror’ which, since the eighteenth century, has given rise to a current of militant pessimism in modern art and literature, represented by the works of Sade , Baudelaire, Lautréamont, Nietzsche, Jarry, Artaud, Genet, Burroughs and Beckett, among others. Perhaps one may think of that ‘nocturnal language’ of which Anais Nin once spoke regarding the writings of Anna Kavan, that lexicon of dreams and alienation.

It is of some historical significance that this nihilistic vision is closely linked to the emergence of new stylistic trends. Most of the authors and poets in this current of development contributed to a revolution in syntax and to the deconstruction of traditional conventions. Barriers between fact and fiction, between spoken and written language, between poetry and prose, have been dismantled in order to express a vision of transmutation – in order to effect a transmutation. Magically this disruption of syntax, literary normality, musical tonality and pictorial representation is symptomatic of the dissociation and psychic dislocation brought about by the first stage of initiation. For many it has become a metaphor of cultural collapse, of the rejection of the telos, of the atomization of the world – a break-down, not a break-through.

In addition to the ultra-nhilist vision there is a second way of seeing which, like the first, was derived mainly from Baudelaire: modernity.

Baudelaire’s followers regarded themselves as more modern than their contemporaries, despite their frequent denunciations of modern beliefs. Although they loathed modern society, they admired modern technology because they regarded the artificial as superior to the natural. This was reinforced by an adherence to Naturalism, a concentration on the depiction of ‘slices’ of modern (urban) life, a challenge to the taboo of ‘morality’. This Naturalism complemented a need to cultivate intensity despite all social limitations: indulgence in perversity could be masked as Naturalistic research or ‘field work’. For Huysmans, the most powerful of the Naturalist writers, such methods offered some way of coming to terms with the otherwise banal exigencies of everyday life. His transition from Naturalism to Decadence, from Downstream to Against Nature, represented a need to augment dry Naturalistic description with some ‘deeper’ more acute vision, even though his subsequent transition from Decadence to Catholicism, from Against Nature to La Cathedrale, represented a retreat into a comfort zone of ‘faith’. The traumatic identity crisis of modernization can often lead to a resurgence of, or relapse into, religion for both the collectivity and the individual.

In most of his critical writings from 1845 Baudelaire, inspired by Poe and Gautier, advocated the theory of ‘the heroism of modern life’. He argued that the artist must oppose the false charm of nostalgia by extracting the essence of beauty from the everyday world – to look for the ‘classic’ in the remote was an error. In her discussion of his aesthetics in her biography of Baudelaire Enid Starkie wrote: ‘Thus all forms of modernity were capable and worthy of becoming classic, and if they did not do so the fault lay with the artist and not with his age.’ The implication of this view, its implicit relativism, and the doubt it casts on orthodox definitions of the real, renders ‘the heroism of modern life’ a disruptive, perhaps magical, idea.

From the alchemical perspective, if the essential beauty of the everyday is equated with the philosopher’s stone, Baudelaire’s theory corresponds to the ancient Hermetic doctrine that the ultimate substance must be distilled from a despised and neglected prima materia. Thus, Rimbaud and Verlaine, in London in 1873, sought the magical and the fantastic in immediate urban images, in ‘modern-Babylonian’ architecture, in The City, in station hotels, in the docks and great iron railway bridges.

This potent urban psycho-geography prefigures the Surrealist poet Aragon, who in 1924, wrote of those other places, ‘sites… not yet inhabited by a divinity’, but where a ‘profound religion is very gradually taking shape’ as though surreality precipitates ‘like acid-gnawed metal at the bottom of a glass’. For the Surrealists these privileged locations were in Paris: the Pont des Suicides at the Buttes-Chaumont, the Porte Saint-Denis, the Tour Saint-Jacques, or the vanished Passage de l’Opera. For us London may take the aspect of a modern Babylon, of a ‘concrete jungle’, redolent with psychic portents and hermetic symbols. Like St Giles High Street, Hungerford Bridge has always possessed features associated with Gateways to Otherness, where – to use Questing jargon – the ‘veil between this world and the next is particularly thin’. And so the poet becomes a shaman of multiple realities, creating the classic from the mundane, distilling the essential from the inessential, revealing ‘heroic’, interpenetrating parallel realities, beside or in-between the interstices of the accepted Real.

But, in order to experience, or even portray the ‘heroism’ of modernity the poet must unlearn preconditioned responses and engage in a critical, initiatory process of dissociation. August Weidmann has shown how this process of ‘dissociation of sensibility’ was a key tenet of Romanticism and fundamental to modern conceptions of art. The Romantics however, tried to gain access to a ‘primordial vision’, whereas it can now be understood that deviation from conventional perceptual norms is, in fact, a way of transmuting the world around us.

In his struggle to apprehend Poe’s ‘supernal beauty’ filtering fitfully through profane sensory mechanisms, the poet uses his or her art to deconstruct, or dismantle, a preconditioned worldview. Understanding of ecstasy, or The Ideal, generates a blackening, or noircissement, as the horror of existence overwhelms the subject with disgust, inducing a hellish night-world experience. However, this dissociation brings a more magical, if not positive, vision – the everyday world loses its narrow, constricted frame of limitation and becomes, thankfully, bizarre.

The poet, through an aloofness or detachment, fleetingly attained in reaction to the disgust provoked by the Nigredo or unregenerate night-world state, perceives that, divorced from everyday functions or associations, ordinary situations, objects, even people, may take on a magical perspective. They acquire an ephemeral, but nevertheless quintessential, glamour, or enchantment of absolute Beauty. But, it will be seen that this ‘absolute’ Beauty, this ‘threshold aestheticism’, is a coniunctio oppositorum, a union of opposites in the Hermetic sense. It contains not only the essential ‘gold’ of supernal beauty, but also a fearful purity of supernal horror – it is not only Naturalistic, but anti-Naturalistic – it is not only soothing but a force which consumes with a unique intensity. It is not only sublime, it is also of The Abyss. It partakes of both elegance and the grotesque. “If I am not grotesque,” said Aubrey Beardsley, that most perfect example of the aesthetic sensibility, “I am nothing”.

Beauty, said Baudelaire, is always bizarre.

A.C. Evans