“Hey, Bob Dylan won the Nobel Prize for Literature.”

—A friend

A friend asked me for my opinion of Bob Dylan’s effect on American poetry. This was my answer:

The Dylan that meant most to me was the Dylan of the 1960s.

I think of him more as a songwriter—a very, very good songwriter—than as a poet, though of course song lyrics are a mode of poetry. (Think of Robert Burns.) Bob Dylan certainly has a gift for resonant, memorable phrases. And the fact that his immense verbal energy was able to touch so many people—was so popular—was definitely invigorating and cheering. I think it is important that the songs he wrote during the 60s had revolution as their central theme. I don’t think that’s true of his work anymore—that theme has dropped out—but it was definitely a factor in his popularity at that time of highly self-conscious, “revolutionary” “change.” He seemed, along with a few others, to be the very voice of the 1960s. He obviously drew energy from Beat writing, but I’m not sure that his work had any effect on poetry as such—though certainly many American poets envied his capacity to interest millions in his work. If rock stars gained a kind of respectability by being called “poets,” many people who were called poets longed for both the vast audiences and the immediacy of response that rock stars were able to achieve. Dylan seemed, then, an embodiment of freedom and hope. And he was young, as everybody was young in the 1960s. He was one of the people to whom Diane di Prima dedicated her book, Revolutionary Letters.

Dylan’s impact on poetry probably had less to do with the quality or techniques of his work than it did with the fact that his work was performed. He was certainly a factor in the rise of “spoken word” or “performance poetry.” The wonderful Alabama poet Jake Berry—whose work is highly experimental and contains many “performative” elements—sees Dylan as one of the people whose inspiration he most cherishes. Indeed, Berry is a songwriter/performer as well as a poet and sees no disconnect between songwriting and writing poetry. Berry’s songs, like Dylan’s, are rooted in folk music and the blues—though he has listened carefully to people like Miles Davis and has experimented with alternative tunings and various other things in his music. Neo Formalist poets—at the opposite pole from Berry—also often cite Dylan in their attempts to defend rhyme in poetry, though their actual work does not resemble Dylan’s and, as far as I know, they don’t write songs.

Here are a few thoughts, written a few years ago, about Dylan’s effect on rhyme in songwriting:

Something happened to rhyming in popular songs in the late 1950s and 1960s. Lyricists like Cole Porter, Ira Gershwin, Irving Berlin, Lorenz Hart, etc. have their roots in “light” verse, which itself goes back to the 17th century. Sir John Suckling, for example:

Out upon it, I have lov’d

Three whole days together;

And am like to love three more,

If it prove fair weather.

Time shall moult away his wings,

Ere he shall discover

In the whole wide world again

Such a constant lover.

Such verse is an elegant, rather aristocratic form. It insists on, among other things, an exactness of rhyme: moon and June rather than moon and fan or fun. It has often been observed that rock n roll put “everybody” (Berlin, Porter, Gershwin, etc.) out of business. The roots of rock n roll are folk song and the blues—forms in which exact rhyming is rarely observed and which appear to be far more demotic than the extremely interesting, often complex but implicitly aristocratic lyrics of Gershwin and Hart. One of Porter’s most famous lines is “Flying too high with some guy in the sky is my i– / dea…of—nothing to do.” The build-up of five rhymes and then the sudden drop. That kind of effect would have little place in a rock and roll song. Bob Dylan’s lyrics are nothing like that—which was one of the reasons people decided to call them “poetry.” Dylan’s brilliant work is rooted in folk songs, blues, a kind of “light” surrealism, and of course Beat poetry. But there is another influence there as well. Dylan talks about it in his memoir, Chronicles, Volume 1. He used to go to the Theatre de Lys to see the then current production of Threepenny Opera. The translation of Brecht’s lyrics by Mark Blitzstein was in the folk song tradition—not in the tradition of Porter, Hart:

You people can watch while I’m scrubbing these floors

And I’m scrubbin’ the floors while you’re gawking

Maybe once ya tip me and it makes ya feel swell

In this crummy Southern town

In this crummy old hotel

But you’ll never guess to who you’re talkin’.

No. You couldn’t ever guess to who you’re talkin’.

Then one night there’s a scream in the night

And you’ll wonder who could that have been

And you see me kinda grinnin’ while I’m scrubbin’

And you say, “What’s she got to grin?”

I’ll tell you.

There’s a ship

The Black Freighter

With a skull on its masthead

Will be coming in

Dylan tells of his fascination with Brecht’s “Pirate Jenny” song as it was sung by Lotte Lenya. (Indeed, Lenya as Pirate Jenny appears on the cover of Dylan’s 1965 LP, Bringing It All Back Home.) A sense of apocalypse and implied revolution is very strong in that song. Obviously, for Brecht, Jenny’s fantasy suggests an uprising of the proletariat. Dylan took the sense of apocalypse and implied revolution from “Pirate Jenny,” but he left behind the notion of the proletariat: that is, he changed the political focus of the song while keeping much of its energy. His 60s songs are all about imminent apocalypse and revolution (“You know that something’s happening but you don’t know what it is, do you Mr. Jones?”), but they are not about the proletariat.

But Dylan was far from being the only one. The aristocratic tradition of elegant, carefully-honed lyrics of Gershwin, Hart and company was swept aside as mainstream music looked not towards “light verse” but towards the kinds of words that people like Alan Lomax and Carl Sandburg had carefully unearthed in their presentations of “folk music.” Porter’s attempt to “co-opt” rock n roll, “The Ritz Roll and Rock,” is, alas, rather pathetic and unsuccessful. The song is danced by the great Fred Astaire—but it is an old Fred Astaire (Silk Stockings, 1957; Astaire was 58):

The Rock and Roll is dead and gone

Since the smart set took it on

Because they found it much too tame

They jazzed it up and changed its name

And all they do around the clock

Is the Ritz Roll and Rock…

These fancy fops and fillies

Throw swell affairs

And make those hick hillbillies

Look like squares

It’s been at least a year, they say

Since any of them hit the hay

And all they do around the clock

Is the Ritz Roll and Rock

The Porter who announced that “They have found that the fountain of youth / Is a mixture of gin and vermouth” or who coined the word “tinpantithesis” is nowhere to be found in that lyric.

By allying itself to folk song, rock n roll shifted from being a music for teenagers to being a new and extremely interesting music for adults. But when that happened, the notion of what constituted “rhyme” in a popular song was drastically changed:

Oh, what did you see, my blue eyed son?

And what did you see, my darling young one?

I saw a newborn baby with wild wolves all around it

I saw a highway of diamonds with nobody on it

I saw a black branch with blood that kept drippin’

I saw a room full of men with their hammers a-bleedin’

I saw a white ladder all covered with water

I saw ten thousand talkers whose tongues were all broken

I saw guns and sharp swords in the hands of young children

And it’s a hard, it’s a hard, it’s a hard, and it’s a hard

It’s a hard rain’s a-gonna fall.

*

There is a tradition in American popular music that goes back not to the blues or to gospel but to a kind of minstrel-show version of African Americans: the “coon” song, a song whose protagonist is supposedly a black man singing in dialect. In their earliest manifestations, such songs were sung by white singers in blackface. One finds examples in Stephen Foster (“De Camptown Races”), George M. Cohan (“I Guess I’ll Have to Telegraph Ma Baby”), Irving Berlin (“Steppin’ Out With Ma Baby”), Johnny Mercer (“Ac-Cent-Tchu-Ate the Positive”), Hoagie Carmichael (“Lazy Bones”), Oscar Hammerstein (“Old Man River”), Ira Gershwin (“It Ain’t Necessarily So”), and many others. In these songs, the purported “black man” was comic and full of malapropisms but he could also be a sort of wisdom figure, a truth teller. (He is that in his manifestation as the monologist “Lord Buckley.”) An interesting aspect of Dylan’s persona is that, though definitely “folk,” he isn’t black. He is perhaps an old Appalachian man, a singer, a guitar player, a bluesman—and a Christian. But what he says and sings is in a way a transformation of the coon song. The singer is definitely related to African Americans, but he is, importantly, like Elvis Presley, a white man who can “do it too.”

There are many influences on Bob Dylan’s lyrics—including the “light” surrealism previously mentioned. (The poet Ted Joans liked to point out that surrealism of a sort was a major feature of Southern black speech: one of his favorite examples was “Shut my mouth wide open.”) The protagonist of Bob Dylan’s songs, their speaker—their “inspiration”—is clearly not Robert Allen Zimmerman and the world a man with such a name might inhabit. He is not even “Dylan” Thomas, the source of Bob Dylan’s pseudonym. He is a white man, probably an older white man, with considerable experience of the world. Though his twang shows that he is clearly not a member of the bourgeoisie or of the college-educated classes, he seems—though a totally fictional creation—authentic. If he is often a wisdom figure, he is also to some degree Norman Mailer’s “White Negro.” He can say things like this:

With your sheet-metal memory of Cannery Row,

And your magazine-husband who one day just had to go,

And your gentleness now, which you just can’t help but show,

Who among them do you think would employ you?

Now you stand with your thief, you’re on his parole

With your holy medallion which your fingertips fold,

And your saintlike face and your ghostlike soul,

Oh, who among them do you think could destroy you?

Sad-eyed lady of the lowlands,

Where the sad-eyed prophet says that no man

Comes,

My warehouse eyes, my Arabian drums,

Should I leave them by your gate,

Or, sad-eyed lady, should I wait?

Or this:

Mama, take this badge off of me

I can’t use it anymore

It’s getting’ dark, too dark to see

I feel like I’m knockin’ on heaven’s door

Knock, knock, knockin’ on heaven’s door

Knock, knock, knockin’ on heaven’s door

Knock, knock, knockin’ on heaven’s door

Knock, knock, knockin’ on heaven’s door

Mama, put my guns in the ground

I can’t shoot them anymore

That long black cloud is comin’ down

I feel like I’m knockin’ on heaven’s door

Like “It’s a Hard Rain,” the second passage echoes the ancient ballad, “Lord Randall,” though the context is here transferred to the American West. Would anyone deny that these words are poetry? But then, so are these, by Cole Porter:

I should like you all to know,

I’m a famous gigolo.

And of lavender, my nature’s got just a dash in it.

As I’m slightly undersexed,

You will always find me next

To some dowager who’s wealthy rather than passionate.

Go to one of those night club places

And you’ll find me stretching my braces

Pushing ladies with lifted faces ’round the floor.

But I must confess to you

There are moments when I’m blue.

And I ask myself whatever I do

It for.

I’m a flower that blooms in the winter,

Sinking deeper and deeper in “snow.” [cocaine]

I’m a baby who has

No mother but jazz,

I’m a gigolo.

Ev’ry morning, when labor is over,

To my sweet-scented lodgings I go,

Take the glass from the shelf

And look at myself,

I’m a gigolo.

I get stocks and bonds

From faded blondes

Ev’ry twenty-fifth of December.

Still I’m just a pet

That men forget

And only tailors remember.

Yet when I see the way all the ladies

Treat their husbands who put up the dough,

You cannot think me odd

If then I thank God

I’m a gigolo.

.

In the still of the night

As I gaze from my window

At the moon in its flight

My thoughts all stray to you

In the still of the night

While the world is in slumber

Oh, the times without number,

Darling, when I say to you,

Do you love me

As I love you?

Are you my life to be,

My dream come true?

Or will this dream of mine fade out of sight

Like the Moon growing dim

On the rim

Of the hill

In the chill,

Still

Of the night?

Jack Foley

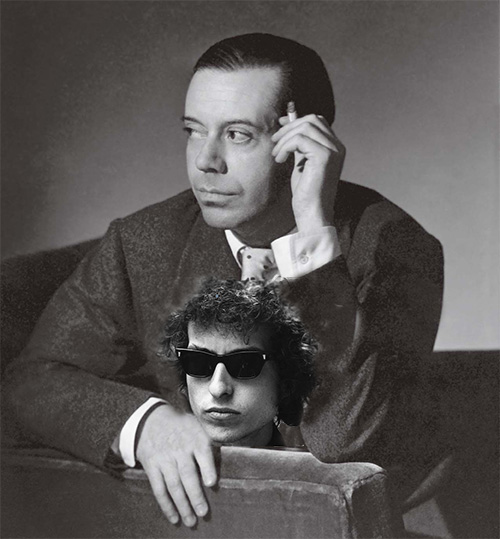

Pic Nick Victor

The link to ‘Bob Dylan And Cole Porter’ repeats the article above it rather than the one that’s actually on Untold

Comment by Larry fyffe on 20 January, 2020 at 12:09 pm