By Sam Whiting

Updated 7:45 pm, Saturday, June 10, 2017

.

Way out in the western hills of Sonoma County where no one can hear it, Owsley “Bear” Stanley’s personal speaker system is cranking Doc and Merle Watson’s version of “Tennessee Stud,” recorded by Bear at the Boarding House in 1974.

With father and son Watson trading flat-pick leads, the sound coming out of those speakers is too clean and rich not to be shared with neighbors and everyone else. So that is what father and son Stanley are finally doing.

On June 23, Starfinder Stanley will release the first of his late father’s legendary “Sonic Journals” in record stores. The seven-CD box set “Doc & Merle Watson: Never the Same Way Once” will introduce an archive of 1,300 tapes recorded live at San Francisco dance halls and nightclubs in the 1960s and ’70s.

Among the 80 artists on tape are Miles Davis on a double bill with the Grateful Dead at Fillmore West, Johnny Cash at the Carousel Ballroom, and Quicksilver Messenger Service at San Quentin, where Bear himself once lived.

The reel-to-reel recordings have been in storage for 50 years or more, which is way too long for history this important. Bear, the renowned sound engineer who built the Wall of Sound for the Grateful Dead, never had the time or money to catalog and transfer his concert tapes to digital files.

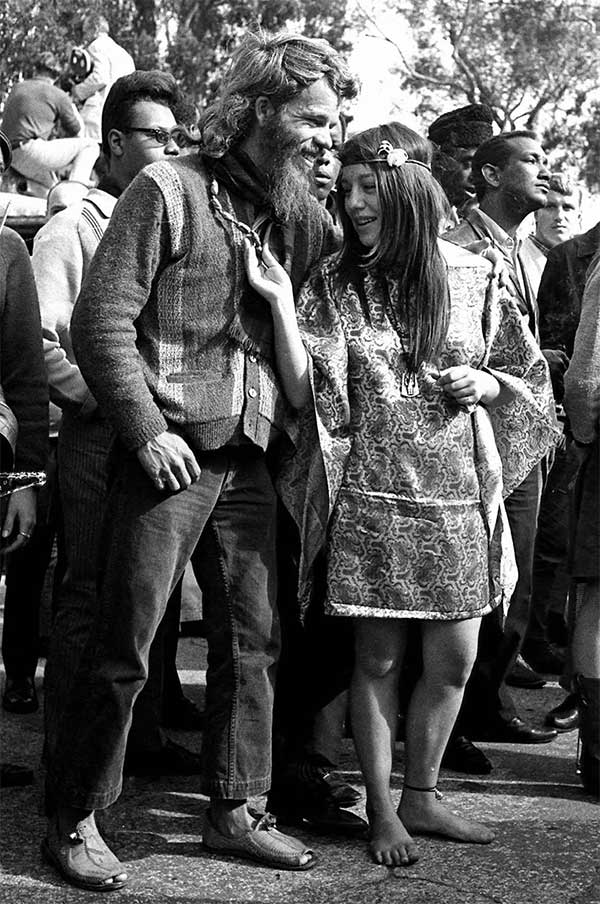

Owsley Stanley tapes Doc and Merle Watson

Media: sam whiting / sfchronicle.com

After he died in 2011, that job was handed down to his son Starfinder, 47, an animal acupuncturist and veterinary doctor. He makes house calls in the tri-city area of Sebastopol, Valley Ford and Two Rock, across the county line to comfort Phil Lesh’s dog in Marin and beyond to San Francisco. On top of these calls is the call of Bear’s concert reels.

“He had told me that if he didn’t manage to deal with the tapes before he died, he expected I would deal with them to his exacting standards,” says Starfinder. “We have to transfer the music off the tapes before the tapes deteriorate and the music is literally lost. … They’ve got a finite life span, and it’s just about up.”

The son of a U.S. senator from Kentucky, Augustus Owsley Stanley III was never called Augustus or Stanley. It was always Owsley or “Bear,” a nickname he earned for his burly physique.

He became a mythical figure in the psychedelic counterculture because he was a master of its two most important components — high-volume concert sound and the synthetic hallucinogens needed to appreciate that sound.

LATEST ENTERTAINMENT VIDEOS

“Owsley had two lives,” says historian and author Dennis McNally. “He was legendary for his production of LSD. But he was also the Grateful Dead sound man and applied the same genius that made him the world’s greatest LSD producer to sound. He contributed massively to the development of entirely new approaches over the next 20 years.”

Whereas other sound engineers would stand at the back of a hall and work a console of switches to equalize the sound, Bear did it by microphone placement, both during the sound check and during the concert itself.

“He wanted the musicians to control their own sound,” Starfinder says. “His job was to capture that sound and make it loud and crystal clear.”

He could be seen leaving his sound board and scurrying up through the crowd and onto the stage during a number. He’d crawl around, moving microphones, plugging some things in and unplugging others. When a set was about to start, the backside of Bear could be seen sticking out from a speaker box while the front side was still inside soldering wires.

“He’s good for a different point of view at about any given time,” Dead vocalist Bob Weir told Chronicle critic Joel Selvin in 2007. “He’s brilliant. He knows everything.”

He’d clutter the stage with twice as many mikes as there were musicians and once he had it right, he would stand at his console and control it all with just the volume knob.

The music would run through the sound board and into Bear’s trusty Nagra reel-to-reel. The tapes were never cut and spliced. They ran through an entire set, and were called “Sonic Journals.”

“He really viewed them as capturing a musical event and not as a recording that could be cut up and overdubbed and reconfigured,” says Starfinder. “What he wanted was to present the show as it was experienced. Its warts and all. He wouldn’t fix mistakes.”

The Sonic Journals first reached the bluegrass market with “Old & in the Way,” a Jerry Garcia side project with David Grisman and Peter Rowan, recorded at the intimate Boarding House on Bush Street in October 1973.

Released on vinyl in 1975, it “was the No. 1 selling bluegrass album of all time before ‘O Brother, Where Art Thou?’ (released in 2000) knocked it off,” says Starfinder, who was too young to remember it.

But he remembers being taken as a teenager to the secure climate-controlled vaults of the Grateful Dead where the Sonic Journals were stored. Each tape was in its cardboard or plastic case notated in Bear’s scribblings. They were lumped together in fruit crates, and he would grab one of them off the shelf at random and read the label out loud. Based on the band, the date and notations like “the Good,” or “Extra Weird,” he’d tell a story.

“Bear had this memory of all of these shows,” Starfinder says. “He’d talk about what mikes he was using and things that happened at the show and before and after.”

All of this institutional knowledge went to Queensland, Australia, where Bear moved in the early 1980s, leaving the tapes behind. He had become convinced that the next Ice Age was coming to the Northern Hemisphere, so he moved to the Southern to live near the Great Barrier Reef. He restricted himself to a meat-only diet, a regimen he had once attempted to foist on the members of the Dead.

“Bear thought he would live forever,” says Starfinder.

He outlasted both throat cancer and heart disease while living on meat, but never got to test his theory on surviving the next Ice Age. He was killed when his car swerved off a Queensland highway, went down an embankment and hit a tree. He was 76.

He left behind his wife, Sheilah, four children by four mothers, eight grandchildren, two great-grandchildren, and those 1,300 reel-to-reel tapes still in their boxes on a shelf in an undisclosed location in Sonoma County.

Their preservation became a family cause, so they formed the Owsley Stanley Foundation, with Starfinder as president.

“I’m the second oldest, but the one that is most like him,” says Starfinder, who was born while his father was in prison for drugs. He was raised by his mother, the former Rhoney Gissen, now a holistic orthodontist in Woodstock, N.Y. Starfinder has degrees from Cornell University and the University of Pennsylvania. “Bear called me his satellite brain,” he says. “That was a high compliment from him.”

The foundation is a 501(c)(3) public charity governed by a seven-member board of directors. Starfinder’s half sister Redbird is the treasurer. The secretary is Bill Semins, a Pittsburgh lawyer who goes by the name “Hawk.” There is a theme at work here.

“I don’t need a middle name,” says Starfinder, when asked if he has one. “I don’t even need a last name.”

To transfer and preserve the tapes without losing any of the detail or subtlety will cost up to $450,000. A chunk of that came when the Dead named the foundation as one of the beneficiaries of the “Fare Thee Well” tour of 2015. That was followed by a November 2015, sold-out benefit at the Great American Music Hall with Hot Tuna topping the bill.

So far, 200 reels have been converted to digital. The selection process includes an “adopt-a-reel” program in which donors of $400 can select a band or even a specific show to transfer, and Hawk will search it out.

But converting a show to digital does not mean that the listening public or even the adopt-a-reel donor will ever hear it.

“Every release is its own tangled path of negotiations with artists and estates,” says Hawk, who serves as executive producer. “We can’t promise that anything will get released to the public. If an artist or a label says ‘no,’ then it won’t get released.”

There are sets by Jefferson Airplane, Santana, early Fleetwood Mac, and all strains of bluegrass, jazz, country, folk, classical, Indian, reggae, Motown and Cajun.

The Watson tapes were chosen to be first because they were made in the mid-’70s when both Bear and Doc and Merle were at the peak of their careers. It also helped that Doc and Merle were not contracted to a label at the time of the shows. Plus there is the hope of capturing that same sales magic of “Old & in the Way,” from the same venue just months before.

Because Bear was a completist, the box set is not a greatest hits package. You get four different renditions of “Tennessee Stud” recorded on four nights. A single night with the crowd banter trimmed out is available on vinyl, and either can be ordered now at www.owsleystanleyfoundation.org

On the CD, Doc Watson, who was blind, is heard to comment, “Look at all these microphones around here. I see one, two, three, four.” That’s proof it was a Bear recording.

“If you turn off the lights and turn up the sound system, you can be transported back in time to the Boarding House in 1974,” says Starfinder’s wife, Audrey, who was born in 1983.

“A lot of us don’t know who these bands were, but now we have a chance to go back in time and hear them and be a part of musical history.”

Sam Whiting is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: [email protected] Instagram: @sfchronicle_art

Starfinder Stanley introduces Bear’s Sonic Journals: http://bit.ly/sonicjournals

CD release: “Doc & Merle Watson: Never the Same Way Once” is $80 at www.owsleystanleyfoundation.org. It will be in record stores June 23.

—