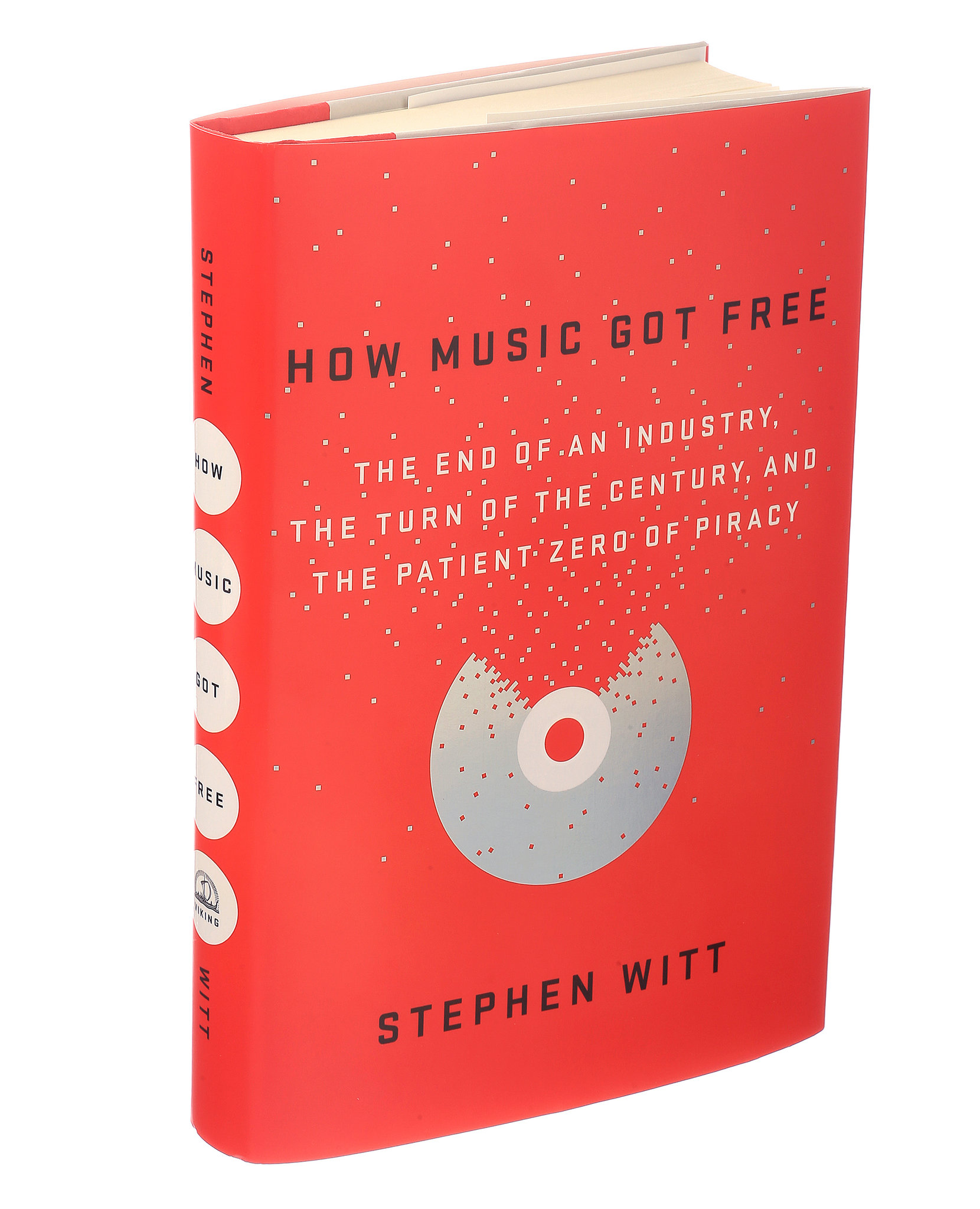

How the Music Got Free, Stephen Witt (£20, Bodley Head, 2015)

Nobody in the UK has made a living as a poet for a long time. They make their living from doing readings, workshops or working in universities and colleges; or having another day job. They certainly don’t make a living wage from book sales (most poetry book sales are usually well under 1000 copies) or writing the stuff. Once you get your head round this, it’s not difficult to decide that readers are more important than book sales, that actually the fact that poetry is not a valuable commodity is oddly liberating. It means you can post your work on websites, get published in zines and magazines, email it here, there and everywhere, and still sell a few poetry books when a publisher obliges.

As a painter as well as a writer, I know that in other artistic areas it isn’t always as easy. If you sell a painting it disappears onto somebody’s wall and all you have left is a photo. Many musicians haven’t quite got their heads round the fact music has become financially worthless, whilst remaining culturally valuable. Lots of time and effort has been spent by some record companies, musicians and bands trying to tighten copyright, fine downloaders, slap cease & desist orders on website owners, just as they did previously when cassette tapes were seen as a problem. (Remember the slogan ‘Home taping is killing music’?)

The trouble is it’s too late. Every obscure piece of music, from every collectable record you could never afford, every band radio session, every mixtape, every about-to-be-released CD, is online if you hunt hard enough. Music has become free and instantly disposable, although the counter-reaction has been a rise in handmade and limited run artefacts: handpainted cassette tapes, limited run CDs in ever-stranger and more inventive packaging. We can argue about the morality of copyright forever, call downloaders thieves as much as you like, but astute musicians have moved on, knowing they can either get their homemade music out to an audience for very little financial outlay, and/or make money by live concerts and merchandising if that is their wont.

Stephen Witts’ book is interesting because it does not engage with any moral or copyright dilemma, it simply documents the story of how mp3 coding and decoding got developed, how the music business chose not to engage with it or the internet, and how one or two people, including a lowly employee at a CD pressing plant, became big time pirates getting pre-release music out onto the internet. Witts does this by focussing on the people involved, that is he develops a cast of characters who populate the 265 pages (plus notes) it takes to tell his story.

So we meet the mad scientist developing programmes, computer software and hardware; our big bad obsessive who wants to post music before anyone else does, and develops a chain of contacts to do so – one of whom is the CD pressing plant guy; and a music industry mogul busy chasing the millions, unable to see what’s happening in front of his eyes. Most of the characters never meet of course, they simply influence and affect each other, are on a kind of collision course with the internet, the law and each other from the word go…

Personally, I’d like to have had more of a discussion about this stuff and how it affects us all in the book, well written and enjoyable though it is. But in a way it’s history; this stuff’s already happened and what is going to happen next is probably more interesting and important. I’ve just read a long article in The Guardian about the possibility and possible shape of postcapitalism, because most, if not all, information (which would include stored music) is no longer worth money – it’s out there for free. This isn’t about stealing music from people, it’s about something bigger: the world changing, markets changing, economies failing and mutating. We all have to face up to this, embrace it, deal with or, or before very it’s going to get even more difficult socially and economically. Welcome to the gift economy and the information age.

Rupert Loydell

love it – bang on – interesting that witt is asking £20 for his book – and can gift rightly be collocated with economy?

Comment by jezdobbs on 31 July, 2015 at 6:25 pm