‘When I think of the punk years, I always think of one particular spot, just at the point where the elevated Westway diverges from Harrow Road and pursues the line of the Hammersmith and City tube tracks to Westbourne Park Station. From the end of 1976, one of the stanchions holding up the Westway was emblazoned with large graffiti which said simply, ‘The Clash’. When first sprayed the graffiti laid a psychic boundary marker for the group – This was their manor, this was how they saw London.’ Jon Savage ‘Punk London’ 1991

‘All across the town, all across the night, everybody’s driving with full head lights, black or white turn it on face the new religion, everybody’s sitting round watching television, London’s burning with boredom now, London’s burning dial 999, Up and down the Westway, in and out the lights, what a great traffic system, it’s so bright, I can’t think of a better way to spend the night than speeding around underneath the yellow lights.’ The Clash ‘London’s Burning’ 1976

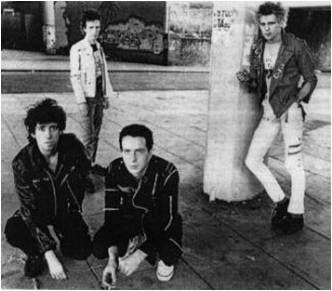

Of all the groups associated with Notting Hill, from Pink Floyd to All Saints and beyond, the Clash have the best street credibility. The punk rock local heroes, Joe Strummer, Mick Jones, Paul Simonon and Topper Headon, represent Ladbroke Grove-North Kensington (W10 rather than 11) in most of the area’s conflicting psychogeographical aspects with the Sound of the Westway.

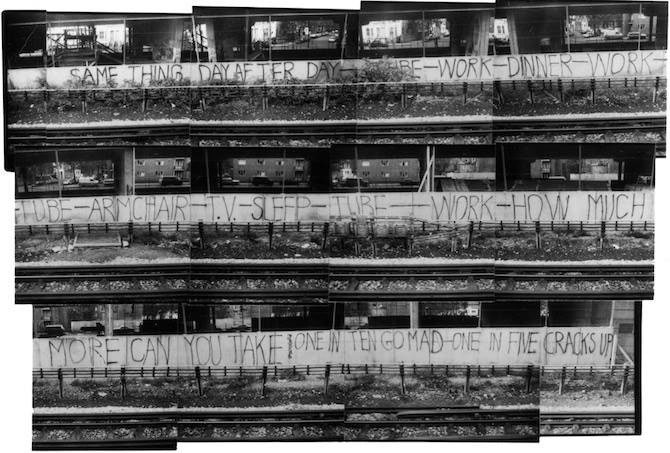

‘Now I’m in the subway looking for the flat, this one leads to this block this one leads to that, the wind howls through the empty blocks looking for a home, but I run through the empty stone because I’m all alone.’ Joe Strummer wrote the lyrics of ‘London’s Burning’ after watching the traffic on the Westway from Mick Jones’ towerblock flat in Wilmcote House on the Warwick Estate. Other influences on the definitive Sound of the Westway Clash anthem are said to be the MC5’s ‘Motor City is Burning’ (about the 1967 Detroit riots), the Situationist ‘Same Thing Day After Day’ graffiti under the Westway, the 1666 Great Fire of London, the JG Ballard novels ‘Crash’ and ‘High Rise’, and speed.

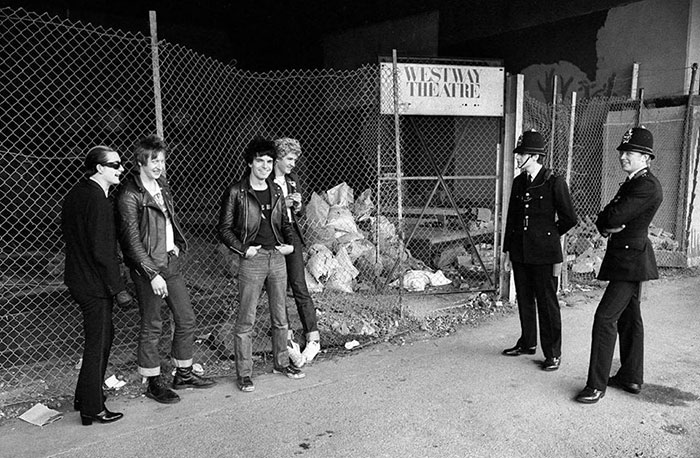

Strummer summed up the psychogeography of the Clash, telling the NME: “We’d take amphetamines and storm round the bleak streets where there was nothing to do but watch the traffic lights. That’s what ‘London’s Burning’ is about.” Roger Matland, who became the director of the North Kensington Amenity Trust (now the Westway Trust) in 1976, recalled: “Early impressions of the Trust land were of its emptiness. It was eerie walking past a boarded-up bay in the evening and seeing 30 or 40 vagrants there round a bonfire.” Mick Jones has recently said: “The music came from the sound of the streets and the Westway.” The group first promoted themselves with a graffiti campaign featuring ‘The Clash’ on a Westway stanchion near Royal Oak, and frequently posed for photos by the flyover, usually at the Portobello-Acklam Road junction.

The first Clash report in NME by Barry Miles (of International Times and Pink Floyd previous) was entitled ‘18 Flight Rock and the Sound of the Westway’ – derived from ‘The Sound of Young America’ slogan of the Detroit Motor City soul label Tamla Motown. Tony Parsons wrote of the first single: ‘White Riot and the Sound of the Westway, the giant inner-city flyover and the futuristic backdrop for this country’s first major race riot since 1958… played with the speed of the Westway, a GBH treble that is as impossible to ignore as the police siren that opens the single or the alarm bell that closes it… a regulation of energy exerting a razor-sharp adrenalin control over their primal amphetamined rush. It created a new air of tension added to the ever-present manic drive that has always existed in their music, the Sound of the Westway.’ Charles Shaar Murray (of School kids Oz previous) advised: ‘Don’t wait for UK messiahs to come down from the Westway with 10 punk commandments.’

In Record Mirror, Tim Lott’s towerblock syndrome ‘Head On Clash’ report featured Paul Simonon reminiscing about high-rise hooliganism, and being evacuated from the Wornington Road school “because the top of Trellick Tower was crumbling.” Lott added: ‘That was in North Kensington, Westway-land. Simonon went to school in the miserable shadow of Trellick Tower, the ugliest building in London. When will it fall?’ Mick Jones gave an even more depressing account of west London life in the 70s, telling Tony Parsons: “Each of these high-rise estates has got those places where kids wear soldiers’ uniforms and get army drill. Indoctrination to keep them off the streets… and they got an artist to paint pictures of happy workers on the side of the Westway. Labour liberates and don’t forget your place.” In ‘The Clash Songbook’ the backdrop of ‘City of the Dead’ (the anti-heroin B-side of ‘Complete Control’) was a grainy shot of the Warwick estate across the flyover. The Westway and the surrounding urban wastelandscape was duly immortalised in ‘Don Letts’ Punk Rock Movie’ and Lech Kowalski’s ‘DOA’ Sex Pistols film as the iconography of punk London.

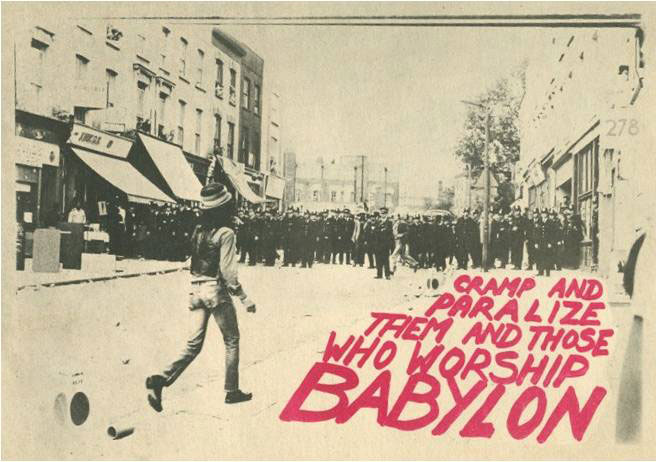

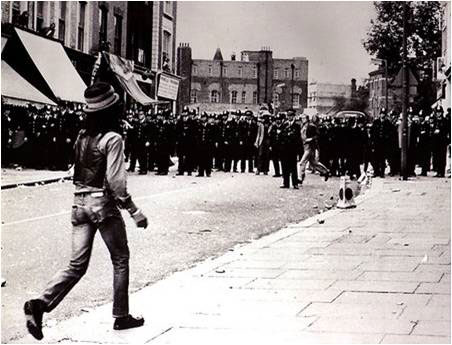

At the 1976 Notting Hill Carnival, as the temperature rose, tempers were lost at what was seen as excessive policing. In due course an attempted arrest under the Westway resulted in Ladbroke Grove’s defining psychogeographical moment – to a soundtrack of the ’76 Carnival hit, Junior Murvin’s ‘Police and thieves in the streets – scaring the nation with their guns and ammunition.’ In ‘The Story of the Clash’, Joe Strummer recalled getting caught up in the first incident. As a group of ‘blue helmets sticking up like a conga line’ went through the crowd, he saw one being hit by a can, immediately followed by a hail of cans: ‘The crowd drew back suddenly and the Notting Hill riot of 1976 was sparked. We were thrown back, women and children too, against a fence which sagged back dangerously over a drop. I can clearly see Bernie Rhodes, even now, frozen at the centre of a massive painting by Rabelais or Michelangelo… as around him a full riot breaks out and 200 screaming people running in every direction. The screaming started it all. Those fat black ladies started screaming the minute it broke out, soon there was fighting 10 blocks in every direction.’

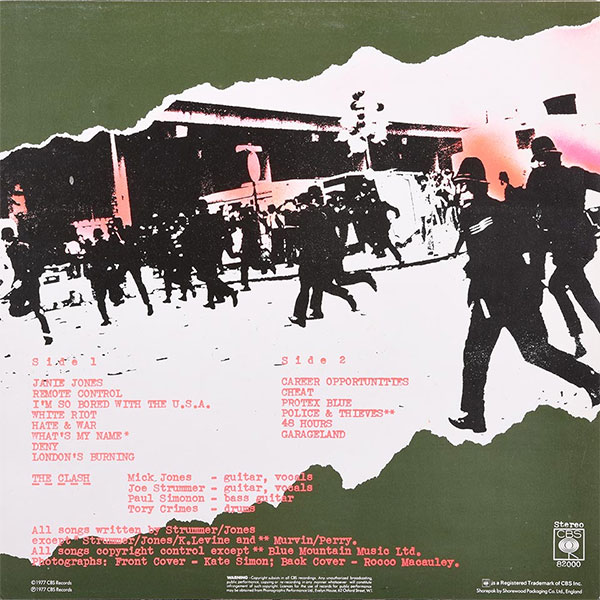

Joe and Paul also recalled an unsuccessful attempt to set a car alight with a box of matches under the Westway. Meanwhile on Portobello Road, a lone Rasta (thought to be Don Letts or Bim Sherman) walked into pop history towards Acklam Road – passing the sound-system outside the Black People’s Information Centre, the former premises of Lord Kitchener’s Valet and Frendz, and a line of policemen across the street. At the same time, Rocco Macaulay began taking his iconic series of photos of the next police charge. Macaulay’s shot of ‘The Clash’ moment when policemen reached the Westway, where the youths had gathered, duly became the back cover of the first album and the ‘White Riot’ tour backdrop projection. The Wild West 10 walk appeared on the sleeve of the ‘Black Market Clash’ mini-LP in 1980 and adverts for Don Letts’ ‘Dread Meets Punk Rockers Uptown’ militant reggae compilation.

Wilf Walker remembers Acklam Road in 1976 as a spiritual awakening of black Britain: “It was incredible in those days to be in a sea of black faces. As a black person, that kind of solidarity we don’t experience anymore… We described it as a demonstration of solidarity and peace within the black community. I can’t imagine what it would have been like for white people… ’76 showed the strength of feeling, reggae was raging in those days. Young blacks weren’t into being happy natives, putting on a silly costume and dancing in the street, in the same street where we were getting done for sus every day.”

As the rioting moved under the Westway, alongside the hoardings sprayed with ‘Same thing day after day – Tube – Work… how much more can you take…’, an old drunk is said to have staggered between the police and youth lines on Tavistock Road at the Portobello junction, causing hostilities to temporarily cease until he stumbled off and fell over a wall. In the ‘Black Britain’ photo of youths on Tavistock Road, rather than militant dread or rude boy style, it was a funky reggae party. Steve Jameson recalled sound-systems playing the Bee Gees’ ‘You Should Be Dancing’. The Sun ‘man on the spot’ in the riot, John Firth, described ‘how I was kicked at black disco’ under the flyover (which must have been Acklam Hall).

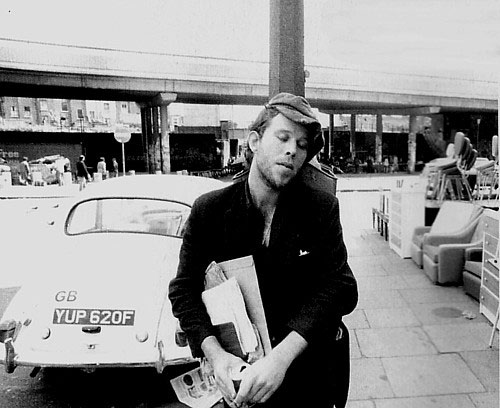

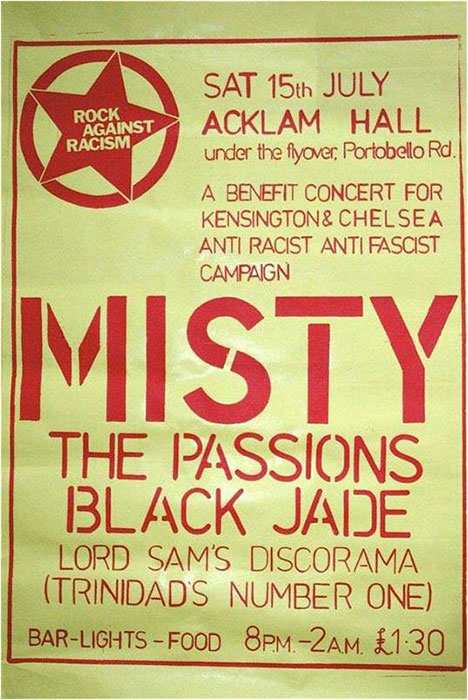

Wilf Walker’s punky reggae party at Acklam Hall began on October 15 with the Black Defence Committee Notting Hill branch benefit ‘in aid of Carnival defendants’; featuring Spartacus R (from the disco group Osibisa who had a hit earlier in the year with ‘Sunshine Day’), the Sukuya steel band, and ‘Clash’ were billed (with no ‘The’) but didn’t actually play, though they were at the gig. Although the Clash already existed, it can be argued that they were a pop culture echo of the 1976 riot like ‘Absolute Beginners’ was of 1958. In ‘Last Gang in Town’ Marcus Gray calls it ‘the catalyst that brought to the surface a lot of disparate elements already present’ in the group. Not least, they got into reggae, feeding dub effects, ‘heavy manners’ stencil graffiti and the apocalyptic Rasta rhetoric into the mix. Aswad had already recorded ‘Three Babylon’ about a police incident under the Westway, and Tom Waits was photographed on Portobello Road north of the flyover before the first Carnival riot.

Along the Westway in Acton, Derek Gibbs and Alan Dearling came up with The Sound of the Westway fanzine. Derek Gibbs, of the Westway Band, Westway Sounds Promotions and the Satellites, also collaborated with Julie Burchill on the New Wave poster mag and appeared on the cover of the ‘New Wave’ punk rock compilation album, spitting at the photographer. Alan Dearling was involved with International Times and BIT. Carol Clerk (later of Melody Maker) wrote in her Acton Gazette review of the fanzine: ‘For punk rockers, the Westway symbolises their music – fast, loud and violent.’

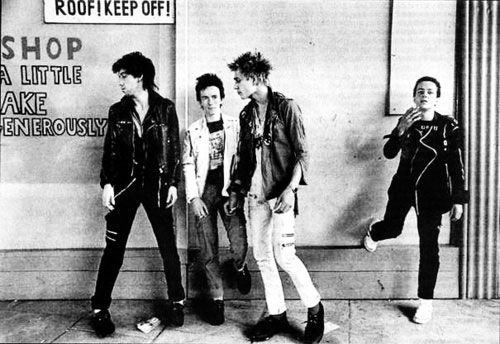

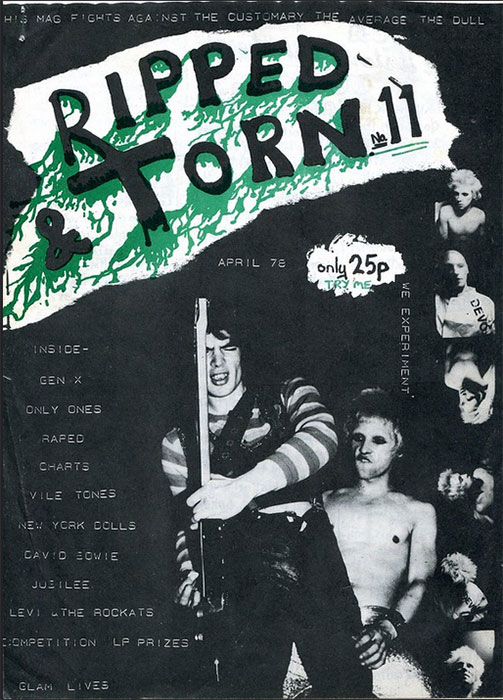

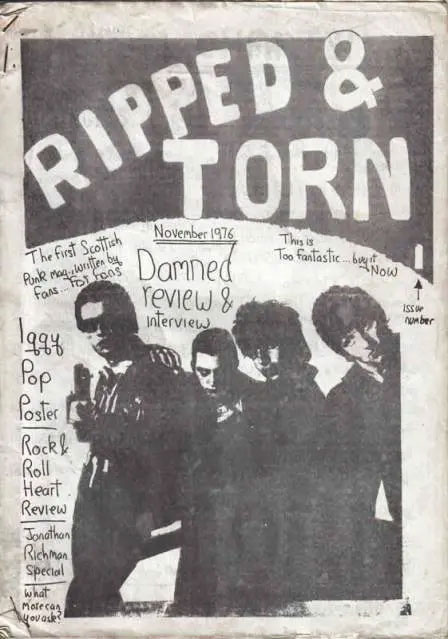

In a Ripped & Torn fanzine review of a punk gig at Acklam Hall, featuring Sham 69, Chelsea, the Lurkers and the Cortinas, the venue was described as ‘functional and dull, and slightly oppressive in its size and stark design, with only a ‘1977’ in cut-out red paper stuck up behind the stage to show that this was a punk concert and not some youth club meeting.’ On the cover of ‘This is the Modern World’, the Jam posed under the Westway roundabout on Bramley Road, in a punky mod homage to Colin MacInnes’s ‘Absolute Beginners’. The Damned were photographed at the Westway Theatre off Portobello Road with a policeman, Generation X posed under the Westway roundabout, and Warsaw Pakt on the footbridge under the flyover, between Tavistock Crescent and Acklam Road.

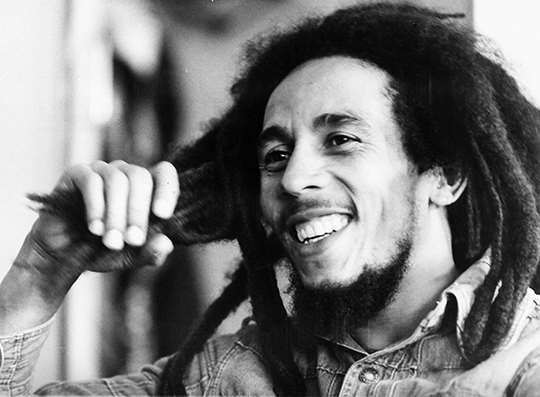

After the Clash ‘White Riot’ tour took the 1976 Carnival riot backdrop around the country in 1977, causing a series of mini-riots, there was another Carnival riot in Notting Hill. This one was attended by Bob Marley, who was on Acklam Road at Lloyd Coxsone’s sound-system, and reporters from International Times (when the office was at 118 Talbot Road) who recorded the ‘Fear and Loathing in W11’:

‘But through it all, slicing through the crowds like shoals of baby sharks, came the kids, the forgotten ones, using their irrelevance to maximum effect, moving in packs of up to a hundred, fast and determined, grabbing everything they passed, snapping camera straps from clenched fists, handbags, pockets, jackets, ornaments, vanishing into the solid mass of the throng… Karma. The dark side of anarchy, mutant children generating panic for the hell of it and sharing the same mind-blistering sweetness in the results. Some of them were only 10 years old. It was the revolution. Unplanned, uncaring and without generals, the black kids were having a revolution. No surprise. In the towerblock prison camps of the working-class, white punks are Xeroxing nihilism with their ‘No Future’ muzak turned up full blast. In the ghetto, when the Carnival slips the leash, black punks tear up the present.’

On the second day, after the procession finished trouble flared up again. Under the Westway, the Kensington Post reporter at the scene Neil Sargent wrote: ’As reggae music belted out from speakers stacked on the north side of Acklam Road, the latest punch up began to move underneath the flyover to a patch of land which usually houses a happy hippy market.’ Then Sargent was attacked by a black youth and rescued by ‘The Clash’ photographer Rocco Macaulay.

In the IT report: ‘The kids had gathered at the Westway, scene of last year’s victorious battle and by 9 O’clock it had become a maelstrom, sucking in curious whites and spitting them out, robbed and battered. Darkness fell and roaming camera lights turned the packed heads into a macabre spot-dance competition in the ballroom of violence. Police blocked all but one exit road and lined the motorway and railroad that swung overhead – wallflowers at the dance of death. By the time the PA system shut down the screaming roar of the riot had made it irrelevant.’ The London Liberal party chairman Gerard Mulholland blamed the ’77 riot on militant reggae music, telling the West London Observer: “The violence that occurred was stimulated enormously by the existence of 3 fixed-place reggae sound-systems in the vicinity of Acklam Road. The natural consequence of reggae is an emotional build up which makes punk rock’s pseudo-anarchy sound like a vicarage tea party. It has no place at Carnival.”

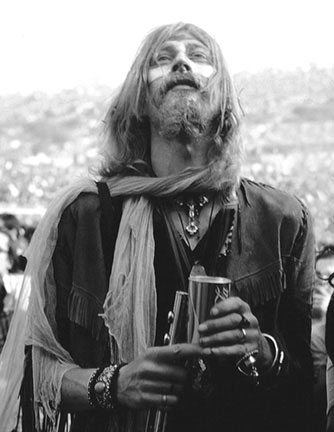

In the 1977 Portobello Guide booklet the stretch of the market either side of the Westway between Lancaster Road and Oxford Gardens was called ‘the Portobello Village’: the ‘alternative quarter’ of ‘reggae music, soul food, underground newspapers, wholewheat bread, Bedouin dresses, art deco objects, natural shoes, herbal medicines, a free shop, brown rice and a gypsy fortune teller’ – the long bearded Romany Gypsy Petulengro Lee. The Free Shop hand sign, sprayed with ‘It’s Only Rock’n’Roll’, is pictured pointing to the hippy recycling centre on the east side of Portobello. Stalls under the Westway included Grass Roots and Retreat from Moscow, which specialised in army greatcoats, 40s rayon dresses, 50s mohair jumpers, Beatle and baseball jackets.

Over on Latimer Road, which was cut in half by the Westway-West Cross Route inter-change, the remaining houses either side became derelict and were squatted – the southern end, by then renamed Freston Road, became a Bohemian interzone of Notting Dale. As the GLC planned a mass eviction before building an industrial estate on the site, in October 1977 the squatters declared themselves independent of Britain and appealed to the UN for assistance. As they set up border controls and embassies, the citizens double-barrelled their names with Bramley from the adjacent road and had Frestonia passports, stamps, a newspaper and national anthem that went: ‘Long live Frestonia, land of the free – not the GLC.’ The Free and Independent Republic of Frestonia was part William Blake Albion Free State and part Marx brothers’ ‘Freedonia’, with some Chestertonesque whimsy and Orwellian nightmare thrown in. Jon Savage produced an issue of his London’s Outrage fanzine consisting of a Frestonia photo montage cut up with the ‘Same thing day after day’ Westway graffiti. He recalls the area in the late 70s as the punk wasteland: “A complete tip. It was basically a rubbish tip with a few squats. It was the worst of the worst, real marginalia, right on the outer limits at one point that place. It was like no-man’s-land.”

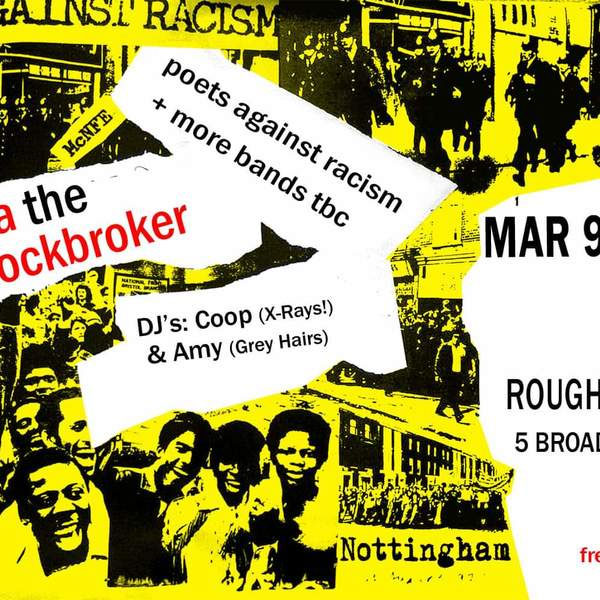

On June 9 1978 Wilf Walker’s Black Productions presented ‘the Grove Music Show’ at Acklam Hall ‘under the flyover’: an Aswad related ‘night of Grove Music’ from Alton Ellis, King Sounds and the Israelites, and Brimstone. Wilf’s celebrated Black Productions’ punky reggae party at Acklam Hall showcased the local reggae heroes Aswad, Barry Ford of Merger, Misty In Roots, Junior Brown, Sons of Jah, and the anarcho-post-punk groups Crass, the Members, the Monochrome Set, the Passions and prag VEC. In the wake of a suspected National Front arson attack on hall, the NME reported that ‘Acklam Hall is almost a natural focal point for any local racial tension. Just underneath the Westway, it stands adjacent to the flashpoint area of the 1976 Carnival riots. The hall is leased from the GLC by Black Productions, who often promote white bands, and has also been used by Rock Against Racism to put on gigs featuring both black and white groups. Theoretically, the hall’s insurance should be covered by the GLC Amenity Trust.’

Misty In Roots appeared at one of these Acklam Hall RAR gigs under a ‘Black & White Unite & Fight’ banner. Viv Goldman began her Sounds review introducing the support band Reality from Kensal Rise: ‘Reality were playing their second gig, and they’re all still at school – in fact, the keyboards player’s mother, a devout Christian, was picketing the Acklam Hall in protest against her son playing heathen music… This particular benefit – organised by the far-sighted Wilf from the enterprising Black Productions outfit – was particularly apt, as it was in aid of black prisoners, and Misty had just heard that their lead guitarist has been sent down for 18 months.’ For Carnival ’78 Wilf Walker presented a local post-punky reggae bill under the flyover: Sons of Jah from Colville, prag VEC from Latimer Road and Matt Stagger. During the Carnival Holger Czukay of Can was photographed recording crowd noise on Ladbroke Grove by the Westway, and Scritti Politti came up with the ’28.8.78’ track consisting of a riot radio report on their ‘Skank Bloc Bologna’ EP. In the ‘Black Britain’ ’78 Carnival photo cheerful revellers, still with some notable Afros, danced along the police line under the Westway.

The NME’s Adrian Thrills praised Black Productions for ‘letting the two cultures clash at the Acklam Hall with their regular punk and reggae gigs every Friday night through the summer without much credit. The community centre-cum-youth club hall is rapidly becoming one of the best medium-sized venues in town.’ Adrian Thrills (previously of 48 Thrills fanzine, named after the Clash lyric) wrote of Barry Ford getting a new band together after Merger split, two days before appearing on ‘Notting Hill’s Acklam Hall stage under the yellow lights of the Westway…Doc Ford and his sidekick, ever-steady bassist Ivor Steadman, must have exchanged nervous glances with the three young session men alongside them, at least as regularly as those who had to walk home from the gig down dingy Portobello Road at 2 in the morning.’ Barry Ford was supported by the Members’ ‘Sound of the Suburbs’, which would land the west London punky pop group a deal with Virgin in Vernon Yard, back along Portobello.

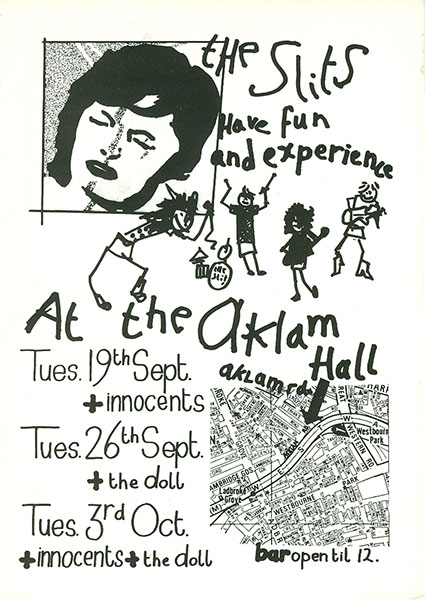

In another bad Ripped & Torn review, at the time of the Slits’ ‘have fun and experience’ white riot girl residency in the autumn, the fanzine’s punk venue guide had on Acklam Hall: ‘The only time I went here I got attacked by a gang of black guys on the way home, that was last year though and things have supposedly improved (with the hand-written note): Saw the Slits there last night and it hasn’t. Due to a series of good billings it’s picked up a good reputation, and I suppose it’s worth going to if there’s a good band on. It’s a large hall type place which lacks atmosphere.’ In the Ripped & Torn gig review the local venue fared slightly better: ‘The Slits were as chaotic as you could expect, and great at it. Their enthusiasm knows no bounds, creating an electric atmosphere which transformed the dingy Acklam Hall.’

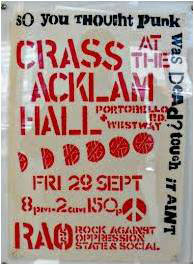

Perhaps the definitive Notting Hill gig ‘under the flyover’ was Wilf Walker’s anarcho-punk-meets-aristo-rock bill of Crass, Teresa D’Abreu, Pearly Spencer and a skateboard display. Teresa D’Abreu of the Sadista Sisters proto-punk S&M burlesque group was the granddaughter of Patrick Bowes-Lyon and a 3rd cousin of the Queen, Pearly Spencer featured Valentine Guinness. The most renowned Black Productions night under the flyover was November 10 1978, with Tribesman, the Valves and the Invaders, as the latter changed their name to Madness. The first Madness gig and some aggro with local skinheads was filmed by Dave Robinson and appears in the 1981 film ‘Take It or Leave It’, in which the ‘Nutty boys get in a ruck after their first gig at Acklam Hall’ and become ‘Madness on the run from a skinhead lynch mob.’ It was also at this gig that Chas Smash is said to have invented the nutty dance. The Edinburgh punk band the Valves were renowned for the ironic surf song, ‘Ain’t No Surf in Portobello’; referring to the Scottish Portobello beach near Edinburgh, although it’s more applicable to the London road.

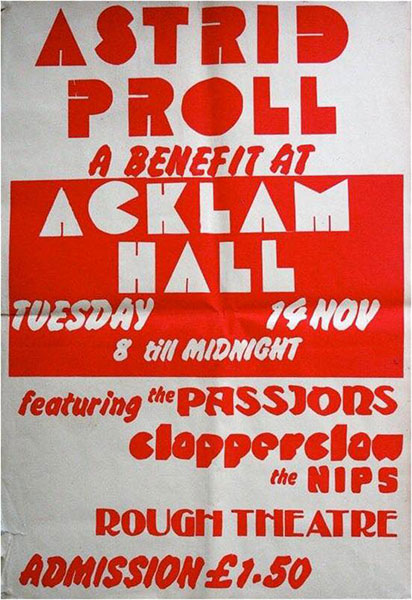

On November 14 the Passions from Latimer Road and the Nips, Shane MacGowan’s pre-Pogues punk band, played an Acklam Hall Rough Theatre benefit for the defence fund of Astrid Proll, the Baader-Meinhof gang getaway driver (better known to the Passions as Anna the mechanic, a youth project worker from Hackney). Scritti Politti made their debut on a classic post-punk bill on November 18, with Red Crayola, Cabaret Voltaire and prag VEC. The Cabs struck the definitive post-punk industrial alienation pose in North Kensington, standing next to a stanchion of the Westway ordained with a poster advertising the gig.

On New Year’s Eve 1978-79 the Raincoats with Palmolive played Acklam Hall, supported by their old drummer Richard Dudanski’s new bands Bank of Dresden and the Vincent Units. The audience consisted of members of the Clash, the Slits, Scritti Politti, prag VEC, Rough Trade staff and music journalists. After a Portobello pub crawl, Robin Banks and Danny Baker made the Raincoats Zigzag’s ‘hot tip for ’79’ and generally praised bedsit bands. Ian Penman of NME wrote of the gig: ‘This was a good place to start ’79, an evening of comedy, parody, high anti-fashion calm, fun, radical rockers and pop feminism a-go-go.’ According to Penman, the Raincoats and Bank of Dresden merged into the Vincent Units-Tesco Bombers post-punk 101’ers local supergroup, creating a mix of Pere Ubu, Big in Japan, Funkadelic and Lee Perry. He described Bank of Dresden (also notable for their local graffiti campaign) as ’sinful-rockabilly-be-bop-dread-beat’, and commended the Raincoats for not conforming to ‘male comforting roles.’

The Rough Trade-Rock Against Racism tour featuring Stiff Little Fingers, Essential Logic, Robert Rental and the Normal stopped off under the Westway as the Rough Trade label released its first album, Rough 1 ‘Inflammable Material’ by Stiff Little Fingers. As well as Cabaret Voltaire, prag VEC, Red Crayola, Scritti Politti, the Raincoats, Passions and Mo-dettes, there were gigs by the Monochrome Set, the Psychedelic Furs and the reggae ‘Roots Encounter’ tour featuring Prince Far-I, Bim Sherman, Prince Hammer and Creation Rebel. Crass appeared again, as their ‘Feeding of the 5,000’ EP came out on Small Wonder through Rough Trade, headlining a benefit for the Angry Brigade-related anarchist Black Cross Cienfugos Press. The hippest Acklam Hall gig to have been at was ‘Final Solution present Music from the Factory under the flyover’ on May 17 1979, featuring the Manchester Factory label’s Joy Division, supported by A Certain Ratio, Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark and John Dowie.

In another good review, Record Mirror’s Chris Westwood wrote of an ill-attended post-punk gig featuring Rema-Rema and Manicured Noise: ‘The Acklam Hall stinks. Like some scummy old school hall, it lacks atmosphere, facilities, everything. Ironically, it remains one of the solitary few places in the big city where crowds of little known quality bands can assemble and present their ideas to open minded punters.’ Nick Tester’s Sounds review of the Raincoats and Passions’ gig continued the ambivalent trend: ‘Tucked squarely beneath the Westway, the clinical confines of Acklam Hall provided an exciting evening of unimpeded expansive music… Tonight, judging by the clamouring at the front, most had come to view the all-girl group Raincoats… The Passions are on last and equally impress. Vocalist Mitch had recently broke his leg nearby to this very venue so he had to be content with shouting from the side of the hall, although he did join the band for an encore of the wry ‘Needles and Pills’… then their set closes in semi-chaos when a flock of skins bent on skull-bashing half-attacked the Passions’ lead guitarist.’

An ad placed in NME by the North Kensington Amenity Trust for the post of Acklam Hall manager announced: ‘Wanted for music venue and community hall in North Kensington. Must be able to get on well with wide range of groups and have experience in bar management and stock control and maintenance of premises.’ As an example of the various post-punk sub cults appearing under the flyover, the surf-punk Barracudas’ frontman Jeremy Gluck was introduced in Sounds as a ‘Canadian singing surfing songs to Ladbroke Grove skinheads.’ ‘Hanging Ten in West London’, Sandy Robertson mused: ‘Seriously would you expect even one of the skinheads who inhabit the feral slums of Ladbroke Grove to have the slightest notion of the origins of terms as arcane as ‘woody’ and ‘ho-dad’? Neither would I, but the imp of the perverse has been at work again, and the Barracudas assure me that the shaven-topped ones who pursue them down Portobello Road are after nothing more than an autographed single.’

At this time a regular feature of Acklam Hall gigs became skinhead aggro, like that which accompanied the Passions, Crisis and Black Encounters gig recounted by Stewart Home in ‘Cranked Up Really High’. He seems to have started a ‘red skins’ v allegedly NF ‘Grove skins’ ‘punk riot’ during the gig, which spilled over Ladbroke Grove into St Charles Hospital. In Hollywood W10, the Acklam skinhead aggro was re-enacted in ‘Breaking Glass’, the Dodi Fayed produced plastic punk film starring Hazel O’Connor as a troubled pop icon. At one point Hazel as Kate Crawley starts a ‘Rock Against 1984’ skinhead riot under the Westway roundabout.

Chris Petit’s post-punk road movie ‘Radio On’ features a driving along the Westway sequence with a soundtrack of Dave Bowie’s JG Ballard tribute ‘Always Crashing in the Same Car’. The poster still is a Ballardesque view from the Westway of the British Rail maintenance depot at Paddington. Another shot of the building ordained with the graffiti ‘No Extradition for Astrid Proll’ appears in the film. The derelict British Rail building was subsequently used as a venue for a Test Department performance and by the Mutoid Waste Company for anarcho raves – then it became the Monsoon hippy revival fashion headquarters (which duly relocated to Freston Road).

Before the last Carnival of the 70s the NME announced: ‘in an effort to alleviate the problems that often arise from the Portobello Green area of Notting Hill, usually the Carnival’s flashpoint, the police and local council have agreed to the Festival and Arts Committee organising a two day concert on the green.’ This was after the Carnival Arts Committee of Louis Chase and Wilf Walker split from the Carnival Development Committee. In 1979 Wilf Walker presented the first Notting Hill Carnival stage, off Portobello Road beside the Westway, in order to include alienated black youth and punk rockers in the event. ‘The lions of Ladbroke Grove’ Aswad topped the post-punky reggae bill at the time of their acclaimed second album ‘Hulet’ – then there was Barry Ford from Merger, Sons of Jah, King Sounds and the Israelites, Brimstone, Exodus, Nik Turner from Hawkwind, Carol Grimes, the Passions and Vincent Units – with power supplied from Carol Grimes’ house.

In spite or because of new riot control measures, enforced by 10,000 policemen, at the Monday closedown there was more trouble. Viv Goldman wrote in Melody Maker: ‘The cans and bottles glittered like fireworks in the street lights, then shone again as they bounced back off the riot shields. The thud thud thud of the impact rivalled the bass in steadiness, suddenly the street of peaceful dancers was a revolutionary frontline, and the militant style of the dreads was put in its conceptual context.’

Probably the worst gig under the Westway took place when Acklam Hall hosted ‘the World’s first Bad Music Festival’, featuring the Horrible Nurds, the Instant Automatons, the Blues Drongo All-Stars, Danny and the Dressmakers, and the Door and the Window. Danny and the consisted of Sister Maura, the stand-in bassist for Shrimp Butty – Colin Seddon, Johnny Brainless, Danny aka Alan Hempsall of Crispy Ambulance on drums, Graham Massey later of 808 State playing guitar under a sheet, and Kif Kif of Here & Now on guitar on a podium. This was the brainchild of JB (Jonathan Barnett, now the director of Portobello Film Festival) and Kif Kif le Batteur aka Keith Dobson of Here & Now and later World Domination Enterprises, who were then operating as Fuck Off Records.

JB also wrote as Jonathan Brainless in International Times, after writing for the NME. The late 70s IT also contained The Beast section featuring Heathcote Williams, the ‘No Extradition for Astrid Proll’ graffiti on Harrow Road, and a review of Neil Oram’s ‘The Warp’ play with London Free School scenes. In the tradition of Hawkwind and the Pink Fairies, Here & Now appeared in Bay 66 under the flyover, on the site of the skateboard park, at an anarcho-hippy-rad-fem-post-punk free gig with Mark Perry’s Good Missionaries, Carol Grimes, and Vermillion and the Aces. Kif Kif’s punk-hippy crossover group also played a BIT benefit at Acklam Hall, the Latimer Road Ceres bakery in the Frestonia Community Centre, and the free Fuck Off festival in Meanwhile Gardens alongside the canal in Kensal.

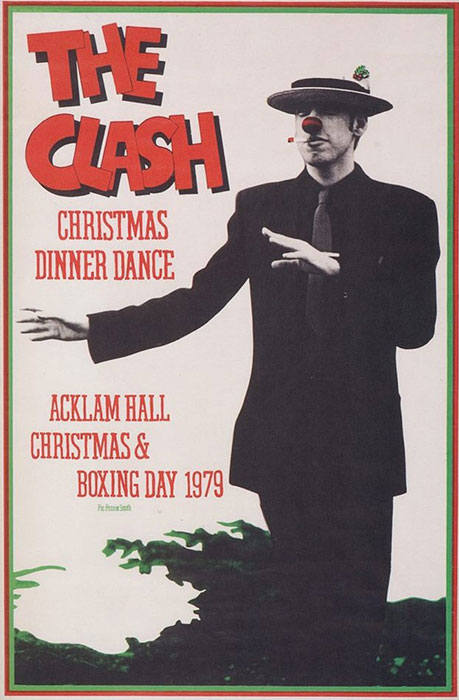

In the last days of the 70s the Clash played Acklam Hall for the first time, previewing their third album ‘London Calling’. The Clash gigs under the Westway also acted as local Christmas parties and warm-ups for the post-Pol Pot Kampuchea-Cambodia benefit at Hammersmith Odeon. Viv Goldman began her Melody Maker review with: ‘A cheery gent looks out of the tiny school-gym-like Acklam Hall and calls out: “Anyone wanna see the Clash? 50 pence.” Invitation is strictly word of mouth because it’s like a block party, the kind they have in New York, where the whole neighbourhood piles into the street and has fun together.’ She praised the local punk, mod and skinhead kids united and drew parallels with the Roxy and the 101’ers at the Elgin as the Clash played their single ‘Keys to Your Heart’.

The last gig of the 70s under the Westway featured Here & Now, Nik Turner of Hawkwind’s Inner City Unit, the Sex Beatles and Splodgenessabounds. In spite of the punk rock and post-punk revolutions, the 70s Sound of the Westway story concluded with Pink Floyd at number 1, with their next single after ‘See Emily Play’, ‘Another Brick in the Wall’ – written by Roger Waters as part of ‘The Wall’ concept double-album-film featuring an adventure playground animation sequence by Gerald Scarfe, influenced by the 1966 London Free School playground on the Acklam Road Westway site. Also at the end of the 70s, Van Morrison released his ‘Bright Side of the Road’ single in a post-punky picture sleeve featuring matchstick figures dancing on Acklam Road by the Westway.

TOM VAGUE