This magical drug mansion in Upstate New York is where the psychedelic ’60s took off

Owned by one of America’s richest families, Millbrook hosted Timothy Leary, Allen Ginsberg, Charles Mingus and more

William Mellon Hitchcock was not your typical acid head.

Billy, as he was called, was a tall, charming blonde stockbroker in his twenties who worked at Lehman Brothers, for one. He was heir to one of the largest fortunes in the country, for another. And he had a trust fund that lined his pockets with $15,000 a week to do what he pleased. Sometimes he played the stocks. Sometimes he dropped acid. In January of 1963, Billy thought it’d be a smart investment to spend half a million dollars on 2,500 acres of land two hours north of New York City on the outskirts of the sleepy village of Millbrook.

German-born gas magnate Charles F. Dieterich bought the land from a Civil War widow in the 1880s, and turned the farm into a game preserve where on the weekends politicians like Governor Nelson Rockefeller hunted deer, pheasants and rabbits. The crown jewel of Daheim, as the estate was then known, was a 64-room Bavarian baroque mansion and gatehouse. After Dieterich’s death in 1927, the estate had passed to William Teagle, president of Standard Oil. By the time Billy Hitchcock bought the farm in 1963, the estate had fallen into disrepair, the dilapidated mansion an afterthought. That is, until Peggy Hitchcock, his impossibly hip 28-year-old sister who turned him onto acid, asked him for a favor.

Drs. Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert, the partners in crime behind the ill-fated Harvard Psilocybin Project, were in bad shape in the summer of 1963 as the Daheim estate sale was being finalized. Earlier that spring, after giving psilocybin to an undergraduate, Alpert became the first Harvard professor in the twentieth century to get fired. (“Some day it will be quite humorous,” Alpert said, “that a professor was fired for supplying a student with ‘the most profound educational experience in my life.’ That’s what he told the Dean it was.”) Leary’s ouster followed days later, for the far tamer reason of failing to show up to teach his scheduled classes.

Leary claimed he knew it was coming from the moment he first tried LSD back in September of 1961. “From the date of this session,” he said, “it was inevitable that we would leave Harvard, that we would leave American society and that we would spend the rest of our lives as mutants, faithfully following the instructions of our internal blueprints, and tenderly, gently disregarding the parochial social inanities.”

Their internal blueprints led them to first to Zihuatanejo, Mexico, then to the island of Antigua, and finally back to Cambridge, $50,000 in debt.

But then along came Peggy Hitchcock, who Leary introduced to LSD the year before and with whom he had a brief affair. In his autobiography, Timothy Leary wrote:

“Peggy Hitchcock was an international jet-setter, renowned as the colorful patroness of the livelier arts and confidante of jazz musicians, race car drivers, writers, movie stars. Stylish, with a wry sense of humor, Peggy was considered the most innovative and artistic of the Andrew Mellon family. Peggy was easily bored, intellectually ambitious, and looking for a project capable of absorbing her whirlwind energy. And that was us.”

She asked her brother Billy if anyone was staying at the boarded up mansion at his recently purchased cattle ranch. “He said no,” she recalled. “So Richard Alpert and I went up and looked and we thought it was great. The rent was a dollar a year.”

In September of 1963, Alpert, Leary, and Ralph Metzner (their colleague at Harvard) moved in, along with thirty or so of their followers. In a Poughkeepsie Journal article headlined “Scientists Plan No Experiments at Millbrook,” Alpert assured the reporter that their drug days were over. The plan was to “write extensively” and “live quietly.”

Standing on the grounds of the cattle ranch, with the waterfalls, meadows, rolling hills dotted with cows, and a rambling Bavarian castle with turrets that looked straight out of a medieval psychedelic fantasy, it’s a wonder the reporter failed to smell the bullshit.

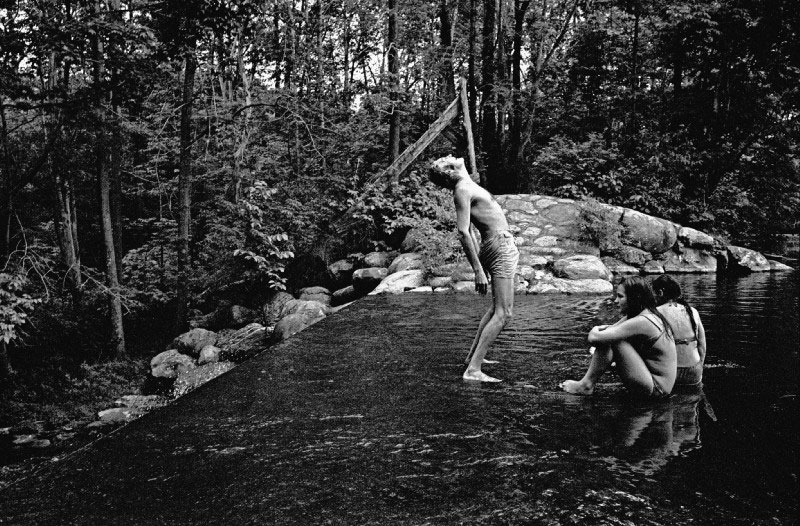

Millbrook provided the perfect setting for Leary and company to explore the limits of psychedelics by tripping hard, and often. (Alvis Upitis/Getty Images)

Though it would be some 30 years before R. Kelly’s “I Believe I Can Fly” hit the radio waves, one can almost hear its faint strings in the background as Dr. Richard Alpert leapt all slow motion-like from a second story window of the Millbrook mansion and tested that ill-conceived notion that would soon come to haunt parents the country over any time those three dreaded letters L-S-D were mentioned. Alas, Alpert did not fly. He broke his leg.

Just another day at Millbrook.

The mansion now renovated and replete with the requisite Persian rugs, pillows, mattresses and psychedelic art, its residents could trip with reckless abandon. It was, as Martin A. Lee and Bruce Shlain put it in Acid Dreams (1985), quite the scene:

“There were large aquariums with unusual fish, while other animals, dogs, cats, goats, wandered freely through the house. People stayed up all night tripping and prancing around the estate. (A stash of liquid acid had spilled in Richard Alpert’s suitcase, soaking his underwear, when the psychedelic fraternity was traveling back from Zihuatanejo, so anyone could get high merely by sucking on his briefs.) Everyone was always either just coming down from a trip or planning to take one. Some dropped acid for ten days straight, increasing the dosage and mixing in other drugs. Even the children and dogs were said to have taken LSD.”

Along with the residents came a rotating cast of celebrities, thinkers and artists. Jazz musicians like Charles Mingus and Maynard Ferguson tested their improvisational skills while playing bass and trumpet high on the roof. Allen Ginsberg and his lover Peter Orlovsky frolicked nude on the grounds. Members of Warhol’s factory drove up when they needed a break from the amphetamine velocity of NYC living. Psychologists both pop and proper, such as Alan Watts, Humphrey Osmond and R.D. Laing, debated theory as Billy Hitchcock talked business with Swiss bankers on the phone.

Ah yes, Billy. Ever in the background at Millbrook, never quite front and center, never quite fitting in, but always around. Billy failed to see any contradictions between his worldly and psychedelic pursuits. Some at Millbrook felt he just didn’t get it, hadn’t quite broken through to the other side. Others suspected his intentions. Why, after all, would an entrenched member of the establishment be so eager to support those seeking to tear it down? But there were tender moments. During one trip, an agitated Billy had to be assured that the estate was really his. At the outset of one group trip where participants went around in a circle stating their questions they hoped to have answered and their intentions for the session, Hitchcock asked: “How can I make more money on the stock market?” Not your typical acid head, indeed.

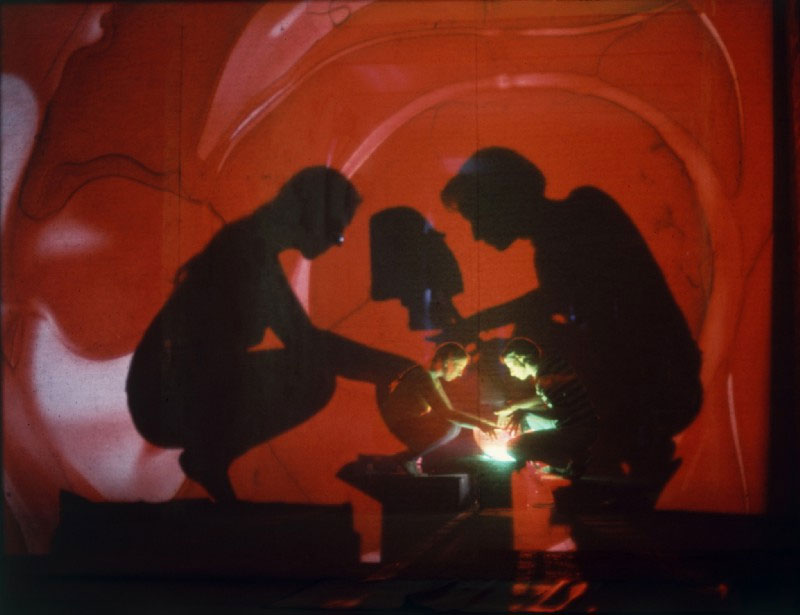

Artists Rudi Stern and Jackie Cassen operate a psychedelic slide show seminar using lights and gels at Millbrook in 1966. (Yale Joel/Life Picture Collection/Getty Images)

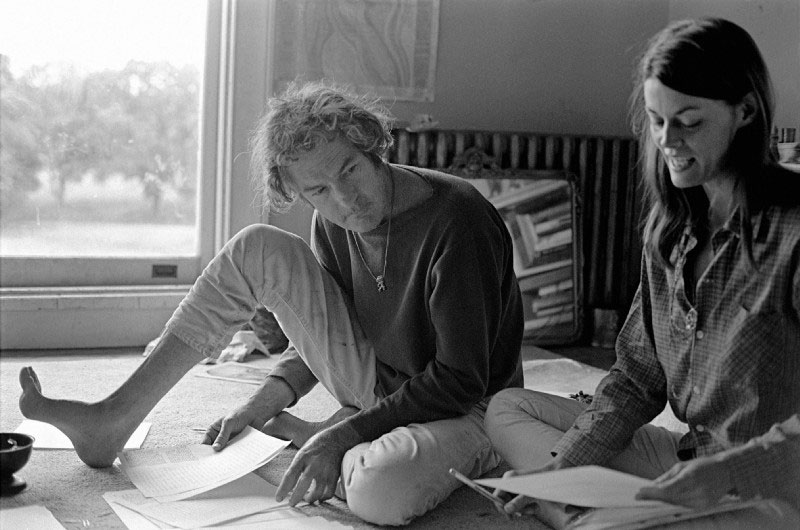

But this experiment in mystical living wasn’t just an endless party. The ringleaders were still academics at heart — plunged deep into uncharted intellectual terrain, to be sure, but compelled nonetheless to map that terrain as best they could.

Leary, Alpert and Metzner were looking for insight into the ultimate nature of reality, to systematize and program the psychedelic experience to reach that place of insight consistently. To that end, Leary, Alpert and Metzner published the journal The Psychedelic Review, held workshops on psychedelics twice a month that were decidedly more sober than the normal shenanigans, and wrote The Psychedelic Experience (1964), a trip manual based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead. (John Lennon, who first took LSD in 1965 after a dentist dosed him and within weeks was dropping acid daily, would compose the revolutionary track “Tomorrow Never Knows” based on passages from The Psychedelic Experience).

But as the months passed, Millbrook started to lose its scientific bearings, the scene growing wilder and wilder as word got out to colleges dotting the East Coast. Residents of Dutchess County grew ever more suspicious. Students at the nearby all women’s Bennett College were shown close-ups of Leary at the start of each term, with administrators warning them that fraternizing with this man would mean instant expulsion. For Leary and his followers, the Buddhist insight that catches hold by about the fifth acid trip that nothing, even the magical paradise of Millbrook, could last forever, turned into creeping fears of an imminent bust.

The interesting thing about Millbrook was just how decadent and middle-class it was. A haven for people who didn’t have to work for a living.

Kesey and the Merry Pranksters visited and, completely bemused by the spaced out “trusties”, who were “carrying the psychedelic torch”, left in a hurry.

Comment by Vaughan Green on 6 March, 2022 at 5:36 am