Book Review of:

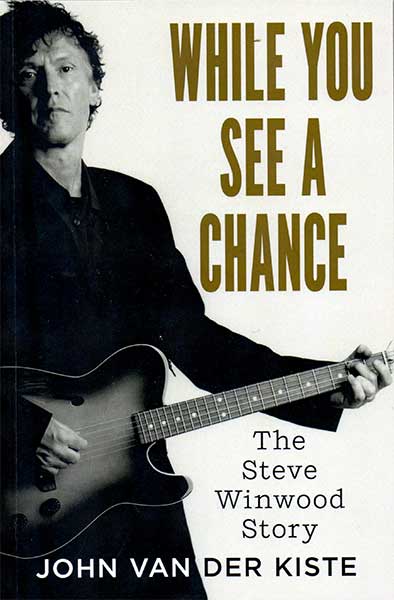

‘WHILE YOU SEE A CHANCE: THE STEVE WINWOOD STORY’

by JOHN VAN DER KISTE (FONTHILL MEDIA)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78155-673-3, Softcover. 158 pages

There’s something about Steve Winwood that tempts even the staunchest rationalist to fleetingly admit the possibility of reincarnation. How else to explain the outrageous talent of such an unassuming young guy, who – from his earliest years, had the ability to pick up any instrument he stumbles across and play it, while others struggle a lifetime to master even one-hundredth of that fluency? Surely there has to have been other previous lives in which earlier incarnations of his supernaturally-enabled spirit had laboured to hone and perfect such levels of dexterity? How else to explain Steve Winwood?

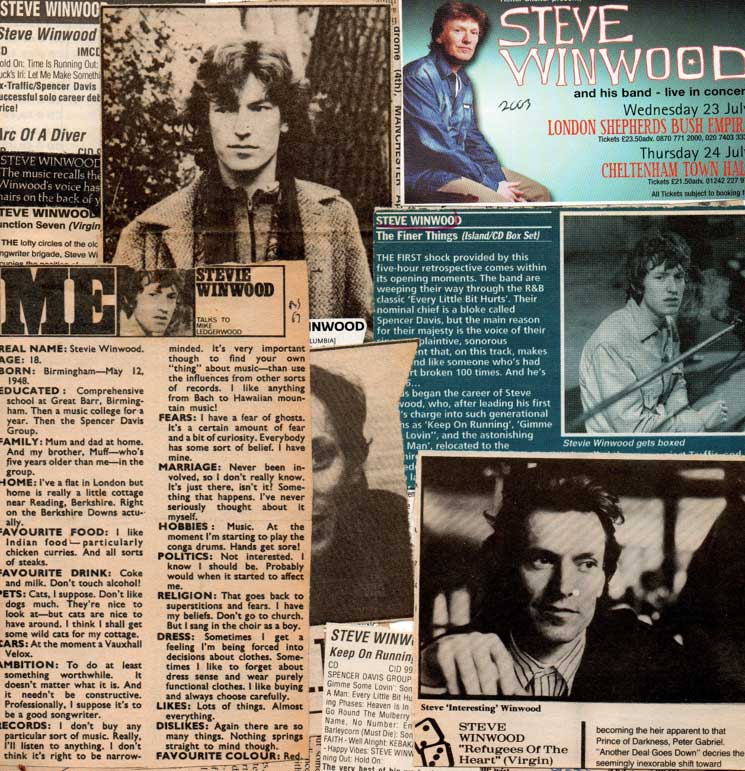

There was a night when every Mod at the Hull Gondola Club wore a checkered lumberjack shirt, because Little Stevie Winwood had worn one on ‘Top Of The Pops’. Island records Chris Blackwell had been out scouting black talent for his fledging label when he came across the Spencer Davis Rhythm & Blues Quartet playing in Birmingham’s ‘Golden Eagle’ pub, with the prodigiously gifted Winwood emoting “Georgia” on blue-eyed Ray Charles mode. Promptly signed to Fontana the renamed group’s first 45rpms were R&B covers. John Lee Hooker’s “Dimples” (August 1964), The Soul Sisters “I Can’t Stand It” (no.47, 5 November), and Brenda’s Holloway’s “Every Little Bit Hurts” (no.41, 18 March 1965). Slow-burners that establish the group presence, before the major hits begin. Now – when James Brown is supermarket background music and Motown a nostalgic movie soundtrack staple, it’s difficult to recapture just how out-there R&B was back then, how transgressive and alien John Lee Hooker or Sonny Boy Williamson sounded. It was cult, in-crowd, word-of-mouth, with no social media and not even a fanzine culture as viral conduit.

Yet there’s an argument that while the enigmatic Winwood saw his chance on several occasions, he deliberately chose not to take it. More intent on being the musician than the star, always more happy as part of an ensemble than playing out front, the precociously-talented protégé was content to hide behind older brother Muff, and group-leader Spencer Davis for his first run of hits. And Jackie Edwards songs “Keep On Running” (no.1, 20 January 1966) and “Somebody Help Me” (no.1, 14 April 1966), then the original “Gimme Some Loving” (no.2, 3 November 1966) were stand-out hits, still strongly featured on all those sixties compilations.

By now it was obvious that Steve’s talents could no longer be contained within such tight confines. Yet, for Traffic they deliberately exclude Dave Mason because of his embarrassing penchant for writing Pop hits. When Traffic play the Hull ‘Skyline Ballroom’, entering the bar, Mason is there in Afghan coat and hairy boots, holding forth to fans and audience. The less sociable Winwood nowhere to be seen. In the book, Van Der Kiste is noticeably reticent about hallucinogenics, devoting more space to apple pies than LSD, although its atmosphere was all-pervasive. The enabler and facilitator of the cultural fluidity that made the ‘Mr Fantasy’ (December 1967) LP possible. And it was a great groundbreaking album.

While Blind Faith was unique in that it was composed of sidemen, none of whom wished to be the focus. There was something about that moment that defines what Rock is, what it was, and what it could have become. When everything was in free fall, when the informal jam was common currency, musicians networking and interacting, drawn by and competing with each other in non-hierarchical ways, measured only by ability and originality, trading and learning off one another, guesting on each others records (frequently incognito due to contractual obligation). Of course there were countless projects talked over through long dope-hazed nights, forgotten in the morning with new propositions and alignments. Yes, Winwood could have joined Led Zep or Crosby Stills & Nash, but didn’t. Futile to conjecture. Blind Faith was incontrovertible. And could have been more. They should have retreated to a house in the country for six months to work into each other like Traffic had done before them. They should have been free from management coercion to tour prematurely and record company pressures to come up with product before they’d got it properly together. What could have been, we’ll never know, although co-operations with Clapton continue.

Then the reconvened Traffic, with floating in-out membership, continue to operate on the free-jam principle through a series of variable albums made up of six (‘The Low Spark Of The High Heeled Boys’, 1971) or five (‘Shoot Out At The Fantasy Factory’, 1973) long improvisational tracks apiece, as the music scene around them lapses back into a tired ego-fed superstar system of Rod Stewart’s and Elton John’s. Like the Beatnik jazzers and BeBop hipsters, the counter-culture goes along with the artist-knows-best idea, respecting the muso’s integrity and credibility, buying into the shock and awe of breakout solos and noodling interplay, unlike the fickle MTV eighties.

Never the natural showman, but with Traffic seemingly having come to a natural end, it’s time for Steve to step out from behind his keyboard. For solo albums. I remember Mike Heron of Incredible String Band enthusing to me about just how good ‘Arc Of A Diver’ (1980) was. Always a group player, sparking off the collective impulse, it was recorded and overdubbed by Steve himself, taking advantage of recent technological advances, in his own studio, with only lyricist outside intervention. Barely thirty-years-old, yet already a veteran of Rock ‘n’ Roll revolutions and evolutions. Never quite Pop, not an entertainer in the traditional sense, but embracing the new reality of corporate sponsorship to deliver a reinvention. While ‘Valerie’ – from the 1982 ‘Talking Back To The Night’ album, only became a UK no.1 when stripped back to a repeated sample by Eric Prydz. Yet rather than venture out solo for a 1994 tour Winwood was joined by Jim Capaldi to justify the Traffic guise for one last time.

There’s a wealth of analytical depth to be written about Steve Winwood and his life of musical reincarnations. While acknowledging Chris Welch to be the authorised biographer, John Van Der Kiste provides an efficient high-flying facts-&-info introduction to a complex musician, meticulously charting his record-by-record evolution, while seldom delving much deeper than his limited page-space allows.

BY ANDREW DARLINGTON