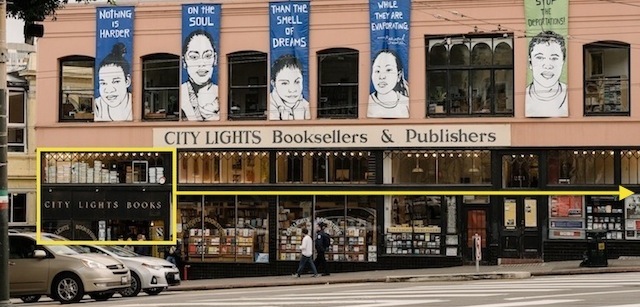

As San Francisco prepares to celebrate Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s 100th birthday on Sunday, City Lights Books will be the focus of much attention. The little paperback bookshop he launched in 1953 is now so large that it occupies an entire block of storefronts and doubles as a North Beach tourist attraction.

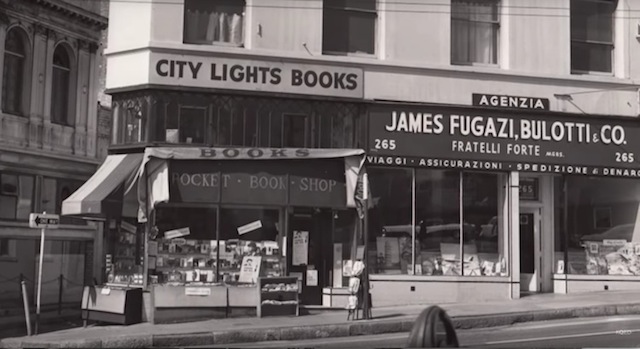

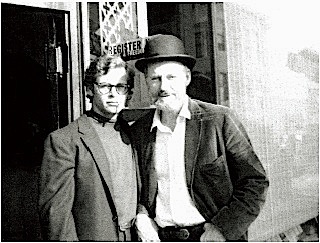

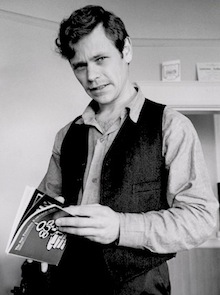

This is what the storefront looked like when I clerked at City Lights in the 1960s.

Here’s an excerpt adapted from My Adventures in Fugitive Literature, later included in The Z Collection:

It was June of 1966 when I looked up a college friend living in North Beach. He was working at City Lights and mentioned me to Shig Murao, who managed the store. Shig was impressed that I had a graduate degree, but he was more impressed that I had dropped out to clerk at the 8th Street Bookshop in New York’s Greenwich Village. 8th Street was not just any bookstore. It had a literary reputation as a sort of East Coast sister to City Lights. The 8th Street owners, Ted and Eli Wilentz, were involved in the small press movement as publishers of Corinth Books. Like City Lights, Corinth was associated with the Beats. Also like City Lights, 8th Street stocked tons of poetry books and mimeo zines of the ’60s, which you wouldn’t have found in the usual mainstream bookstores. Shig hired me on the spot.

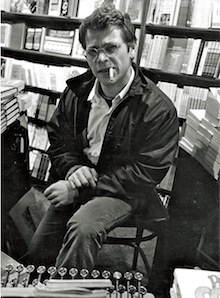

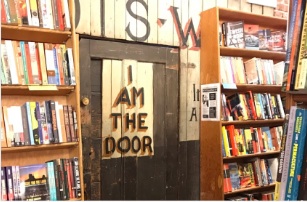

To be a clerk at City Lights was an intimate privilege. Far more bohemian than 8th Street, City Lights had the atmosphere of a funky Left Bank cave with flimsy cellar bookshelves partly made of orange crates, some rickety chairs and café tables for reading, and a lone clerk sitting at the top of the stairs by the front door ringing up sales on an old-fashioned cash register. Lawrence still took an occasional turn at the register. And if Shig had confidence in you, he left you alone to do your thing.

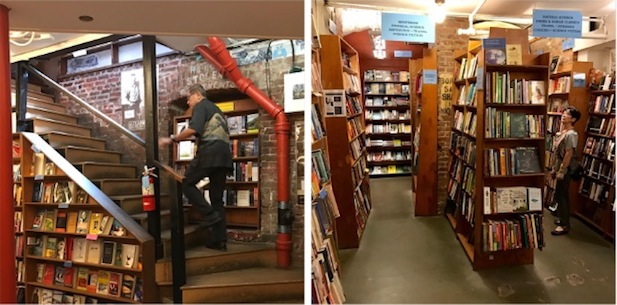

Photo by David Tom, 2017

At some point he gave me a key to the store and asked me to open up on Sunday mornings. The streets of North Beach would be deserted. Across from the store, at Columbus and Broadway, the topless clubs would be closed. The morning sunlight would be sharp and bright, and I recall the pleasure of sitting at the cash register reading undisturbed for as much as an hour or two until the first customers began drifting in.

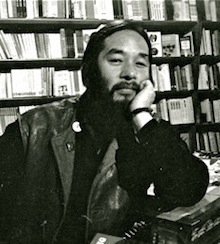

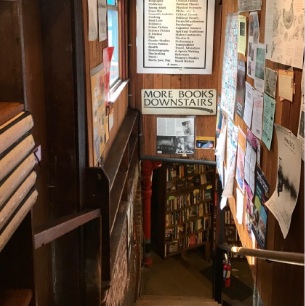

Photo by David Tom, 2017

One of the great things about clerking there was that you met everybody who came through the door. You were like a gatekeeper. The people who walked in could be anybody. You met all kinds. Bill Graham, the rock promoter, showed up once a week with his Fillmore concert posters to put in the window. Honest-to-god poetry lovers stopped by to check the mimeo magazines. A guy in a three-piece suit came up from the basement one time with $80 worth of mimeos under his arm. He turned out to be D.J.R. Bruckner, Chicago bureau chief of the Los Angeles Times, later on Nixon’s enemies list. Bob Kaufman, the poet of Solitudes, would appear suddenly just inside the door and rock back and forth, his eyes fluttering. He was like a ghost. Never said a word. Neal Cassady blew in once. He wanted to cash what was more than likely a bad check. Lawrence had called ahead, “Don’t give him any money.” I didn’t. Cassady was offended, but jaunty about it. “Some millionaires don’t even put salt on their table,” he said, and blew back out.

Photos by David and Sharon Tom, 2017

After I’d been a clerk for about a year, Shig told me Lawrence was looking for an editorial assistant. Why didn’t I ask him for the job? By then the City Lights shipping department had grown too large to remain hidden behind the cellar bookshelves. Lawrence moved the operation to a corner storefront on upper Grant Avenue and put his editorial office in a small apartment above it.

He told me he needed someone to handle permissions requests, publishing correspondence, some of his own mail, and editorial chores like proof reading. Was I willing? It was a step up from the cash register. Of course I was willing. For the next two years we shared a room overlooking Filbert Street. Lawrence’s desk, an old-fashioned rolltop, was in one corner. My desk was in another corner. A second room had a futon on the floor and little else. A third closet-size room held the editorial files.

I’ve been asked what it was like working for Lawrence at such close quarters. I found him an easy boss to work for. He was clear in his expectations. He didn’t look over my shoulder or try to micromanage whatever I was doing. He was also very self-contained. Never gossiped. Rarely made small talk. His reputation for being tight with money was true, but contrary to Cassady’s insult, he was generous with his possessions. There were times he lent me his cabin in Big Sur, and when I didn’t have a car he gave me his VW bus to get there.

Had I stayed in New York I might never have done a little magazine. But the intimacy of the Bay Area literary scene, which teemed with poets, combined with the advantage of my position at City Lights, which was a nexus for San Francisco’s small-press publishers, spurred me to it. My co-editor at first was Gail Dusenbery (née Chiarello), a veteran of the 1965 Berkeley Poetry Conference. She had been part of two circles of budding poets, one led by Robert Duncan and the other by Gary Snyder. Oyez Press had recently published her first book of poems, The Mark. It was Gail who came up with a name for the magazine: The San Francisco EARTHQUAKE. Naturally I asked Lawrence for a contribution to the first issue, which appeared in the fall of 1967. He gave me a diaristic account of his trip to Berlin earlier that year for the Literarisches Colloquium in Wannsee. His really significant contribution, however, was a generous offer to put the magazine in the City Lights catalog. This meant nationwide distribution, which it would not have had otherwise. By the second issue my closest collaborators were Carl Weissner, Mary Beach, Claude Pélieu, and Norman O. Mustill. It was a crazy crew, and we had a great time while it lasted.

It is very evocative to look down those stairs again (even if they are probably not the same old creaky ones I used to know). Must have been only 14 when I first ventured into CL and cautiously went down into some unknown beatnik murk and madness. I was particularly charmed by the notice board on the right, with weird posters, strange notes and many letters from foreign parts addressed “C/O”, waiting until whatever wandering poet or saint they were intended for happened to turn up.

yep, i should’ve mentioned the notice board. a nostalgic throwback. that board drew lots of customers in the old days. it’s nice to know they’ve kept it. i mentioned that all kinds of people used to walk in the door, but i forgot to mention the shoplifters — they were legion — and the occasional “till tappers” that shig use to warn me about. i did keep an eye out for them. but one day a guy came in and kept pointing sort of helplessly to a book in a corner shelf off at floor level near that staircase away from the cash register. i finally got out of my chair, thinking i was being a righteous book clerk by giving him a hand when, as i was bending lower and lower, i heard the old-fashioned ring of the register drawer. i bolted upright just in time to see someone fleeing out the door with a handful of bills. obviously a confederate. it had never occurred to me that that would be a till-tapper’s m.o. i chased the confederate past Vesuvio’s down Columbus until half way to Kearny he threw some bills out of his pocket. naturally i stopped to pick them up and rushed back to the store to make sure the whole damn register was still there. it was, of course. i thought, oh boy! i just saved the day!! until i looked at the bills in my hand. nothing but singles!! they got all the tens and twenties!!! hah. outsmarted again.