…interspersed with memories of Granada and reading Leonard Cohen

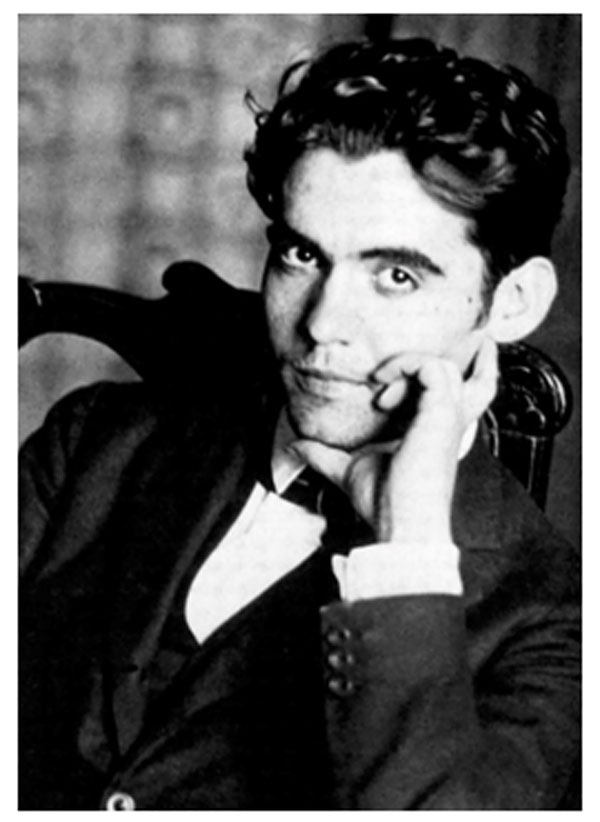

Reading Lorca always fills me with a deep sense of anguish and longing. I think it is because his poems contain, in their essence, a profound sensitivity of human suffering. Poem of the Deep Song is no exception, written when the poet was only 23 years old. This collection consists of 55 poems, grouped into 10 sections along with a prologue poem. They were composed mostly in the winter of 1921, while Lorca was helping to organise a flamenco contest in Granada. It was only in 1931, a decade later, that the poems were published. The original manuscript was fairly untouched, but Lorca added two dramatic dialogues that he wrote in 1925 to the collection. Lorca was deeply moved by the folkloric musical tradition of flamenco, and particularly that of the canto jondo, which translates to “deep song”.

In the lecture he delivered at the flamenco festival in Granada in 1922, Lorca described flamenco as an offshoot of the much older tradition of canto jondo, the latter tracing back to the primitive musical systems of India. Canto jondo makes frequent use of the semitone, which is not found in our modern scale, and in doing so he claimed that it “bears the naked shiver of emotion of the first oriental peoples.” Lorca felt these age-old traditions were being lost, and that the musical soul of the race was in “grave danger”. It was for this reason that he helped to organise the flamenco festival in Granada, to preserve the dying tradition of canto jondo and salvage the beauty that is contained therein.

The poems often speak of the past. In ‘The Six Strings’, for instance, he beautifully captures the way a guitar evokes previous generations:

The guitar

makes dreams weep.

The sobbing of lost

souls

escapes through its round

mouth.

In this poem, as in many of the others, Lorca breathes life into the tradition of canto jondo with his words. By reading his poetry, we too can experience that profound sense of anguish and longing that he was able to hear in the music of canto jondo. We are taken on a journey to recover a sense of our common humanity going back through time, along the unbroken chain of who we are as a species to the dawn of the first civilizations.

***

A few years ago, I bought a guitar in the north of Spain and travelled south with a group of street performers to Granada. Sitting by a gentle stream in the shade of the Alhambra, I strummed a few chords as the sound of voices floated on the warm breezes of the afternoon. It was a dreamy summer. My heart was young and hungry for adventure. I had not read Lorca then, but as I do now, sitting under a grey sky on a cloudy afternoon, I am transported back to Granada. To walking between crumbling buildings on the narrow cobblestone streets, and among the century-old olive trees in the orange-scented air with the breathless wonder of the Andalusian hills fading off into the distance.

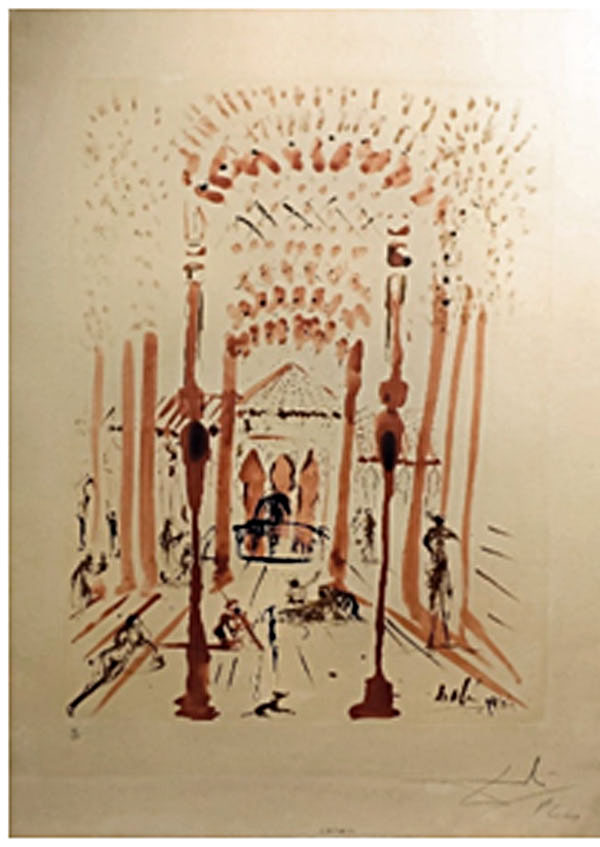

Salvador Dalí, Alhambra (1964)

How drizzly and dull my life seems now when I think of that summer, but in Lorca’s poetry I find a sense of familiarity and freedom that gives my spirit wings once more. I cannot help but feel disheartened at how this young man could crystalise the magic of Andalusia so beautifully in words, and all my poetry seems to pale by comparison into a small insignificant fluttering of loose scribbles on discarded pages in my room. I have nothing to offer but the ragged fragments of my own heart. But in some way, perhaps, the spirit of Lorca lives on through my work, and I hope that will offer any readers of my poetry a small degree of consolation. After all, poetry in whatever shape or form it arises, is of one and the same essence, springing from the fountain of our common sufferings and desires.

After returning to London to complete my undergraduate degree in anthropology, I discovered the music and poetry of Leonard Cohen. I was listening to music on Spotify one day, and a song came on from his second album, ‘Songs From A Room’. Anyone who is familiar with his music will recognise the following lines, which resonated deeply with me at the time, and still do:

Like a bird on a wire

Like a drunk in a midnight choir

I have tried in my way to be free.

I must have replayed the song about five times just to hear those words again. They were so soothingly true, and his voice carried them with such a tragic grace that I was moved to the very core of my being. It awoke that sensation again, that longing for the freedom of the Andalusian hills. I was on my year abroad at the time, studying at the University of Texas at Austin, so I went to the library and took out a collection of his poems. I subsequently learned that Leonard Cohen was a poet and a novelist for about ten years before he began his career as a singer-songwriter.

That was my first real venture into the world of poetry, and it was through Leonard Cohen that I first learned about Lorca. He owed a great debt to Lorca, because it was Lorca that initially gave him a poetic voice. I read these poems over and over again, letting the words sink into my soul. Then I started to cross out certain words and change them according to what I felt, and I didn’t erase the scribbles in the book before I gave them back so to this day there is a book somewhere in the poetry section of a library in Texas containing Leonard Cohen’s poetry that is full of my scribbles. Going back to Lorca now is like coming full circle.

***

In 1937, Lorca was murdered by the right-wing militia at the start of the Spanish Civil War. He was buried in an unmarked mass grave and his remains were never found. Eerily, he wrote a poem almost a decade earlier that predicted his own violent death and the mysterious remains of his body, called ‘The Fable And Round of the Three Friends”:

Then I realized I had been murdered.

They looked for me in cafes, cemeteries and churches

…. But they did not find me.

They never found me?

No. They never found me.

But Lorca lives on. He lives on in the lives that he inspired, in the lyrical genius of Leonard Cohen and many others. His body may be gone, but his spirit remains with us. We can read his work today and be moved by his sympathy and talent. We, the poets and lovers of this world, are forever in his debt.

Gilles Madan